The American Promise: Printed Page 559

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 513

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 582

The Farmers’ Alliance

At the heart of the farmers’ problems stood a banking system dominated by eastern commercial banks committed to the gold standard, a railroad rate system both capricious and unfair, and rampant speculation that drove up the price of land. In the West, farmers rankled under a system that allowed railroads to charge them exorbitant freight rates while granting rebates to large shippers (see “Railroads, Trusts, and the Federal Government” in chapter 18). The practice of charging higher rates for short hauls than for long hauls meant that grain elevators could ship their wheat from Chicago to New York and across the Atlantic for less than a Dakota farmer paid to send his crop to mills in Minneapolis. In the South, lack of currency and credit drove farmers to the stopgap credit system of the crop lien. To pay for seed and supplies, farmers pledged their crops as collateral to local creditors (furnishing merchants). Determined to do something, farmers banded together to fight for change.

Farm protest was not new. In the 1870s, farmers had supported the Grange and the Greenback Labor Party. As the farmers’ situation grew more desperate, they organized, forming regional alliances. The first Farmers’ Alliance came together in Lampasas County, Texas, to fight “landsharks and horse thieves.” In frontier farmhouses in Texas, in log cabins in the backwoods of Arkansas, and in the rural parishes of Louisiana, separate groups of farmers formed similar alliances for self-

The American Promise: Printed Page 559

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 513

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 582

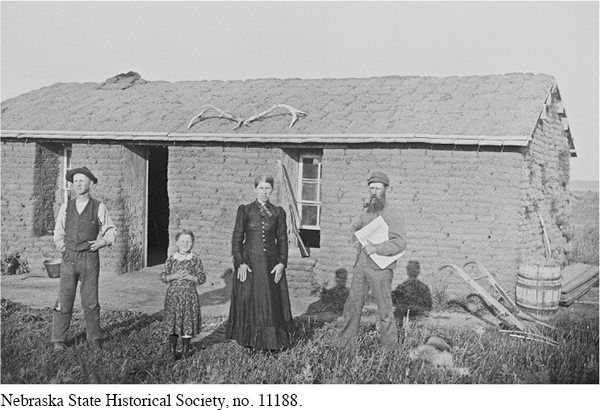

Page 560As the movement grew in the 1880s, farmers’ groups consolidated into two regional alliances: the Northwestern Farmers’ Alliance, active in Kansas, Nebraska, and other midwestern Granger states; and the more radical Southern Farmers’ Alliance. Traveling lecturers preached the Alliance message. Worn-

Radical in its inclusiveness, the Southern Alliance reached out to African Americans, women, and industrial workers. Through cooperation with the Colored Farmers’ Alliance, an African American group founded in Texas in the 1880s, blacks and whites attempted to make common cause. As Georgia’s Tom Watson, a Southern Alliance stalwart, pointed out, “The colored tenant is in the same boat as the white tenant, . . . and . . . the accident of color can make no difference in the interests of farmers, croppers, and laborers.” The Alliance reached out to industrial workers as well as farmers. During a major strike against Jay Gould’s Texas and Pacific Railroad in 1886, the Alliance vocally sided with the workers and rushed food and supplies to the strikers. Women as well as men rallied to the Alliance banner. “I am going to work for prohibition, the Alliance, and for Jesus as long as I live,” swore one woman.

At the heart of the Alliance movement stood a series of farmers’ cooperatives. By “bulking” their cotton—