The American Promise: Printed Page 613

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 559

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 636

Progressivism for White Men Only

The American Promise: Printed Page 613

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 559

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 636

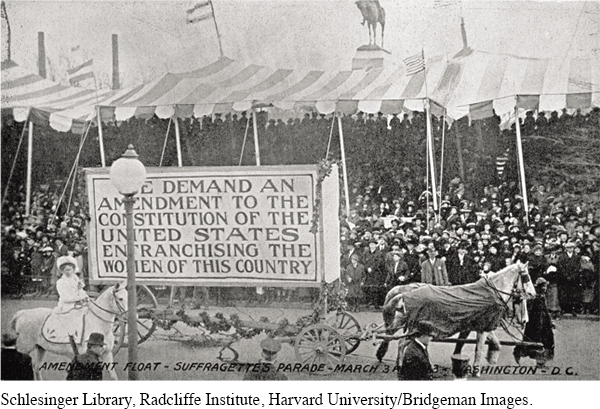

Page 613The day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration in March 1913, the largest mass march to that date in the nation’s history took place as more than five thousand demonstrators took to the streets in Washington to demand the vote for women. A rowdy crowd on hand to celebrate the Democrats’ triumph attacked the marchers. Men spat at the suffragists and threw lighted cigarettes and matches at their clothing. “If my wife were where you are,” a burly cop told one suffragist, “I’d break her head.” But for all the marching, Wilson pointedly ignored woman suffrage in his inaugural address the next day.

The march served as a reminder that the political gains of progressivism were not spread equally throughout the population. As the twentieth century dawned, women still could not vote in most states, although they had won major victories in the West. Increasingly, however, woman suffrage had become an international movement.

Alice Paul, a Quaker social worker who had visited England and participated in suffrage activism there, returned to the United States in 1910 in time to plan the mass march on the eve of Wilson’s inauguration and to lobby for a federal amendment to give women the vote. Paul’s dramatic tactics alienated many in the National American Woman Suffrage Association. In 1916, Paul founded the militant National Woman’s Party, which became the radical voice of the suffrage movement.

Women weren’t the only group left out in progressive reform. Progressivism, as it was practiced in the West and South, was tainted with racism by seeking to limit the rights of Asians and African Americans. Anti-

The American Promise: Printed Page 613

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 559

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 636

Page 614South of the Mason-

The Progressive Era also witnessed the rise of Jim Crow laws to segregate public facilities. The new railroads precipitated segregation in the South where it had rarely existed before, at least on paper. Soon, separate railcars, separate waiting rooms, separate bathrooms, and separate dining facilities for blacks sprang up across the South. In courtrooms in Mississippi, blacks were required to swear on a separate Bible.

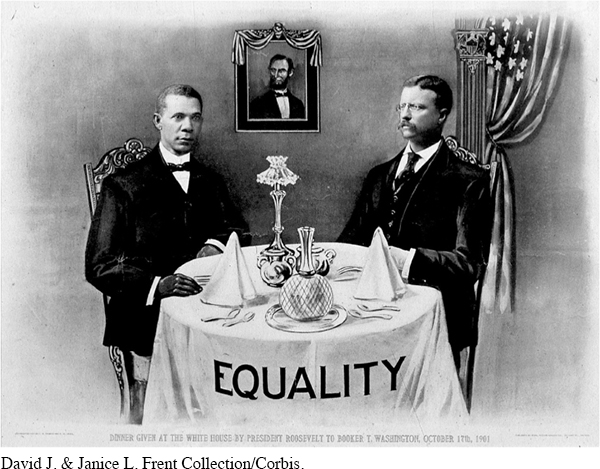

In the face of this growing repression, Booker T. Washington, the preeminent black leader of the day, urged caution and restraint. A former slave, Washington opened the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1881 to teach vocational skills to African Americans. He emphasized education and economic progress for his race and urged African Americans to put aside issues of political and social equality. In an 1895 speech in Atlanta that came to be known as the Atlanta Compromise, he stated, “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” Washington’s accommodationist policy appealed to whites and elevated “the wizard of Tuskegee” to the role of national spokesman for African Americans.

The American Promise: Printed Page 613

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 559

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 636

Page 615The year after Washington proclaimed the Atlanta Compromise, the Supreme Court upheld the legality of racial segregation, affirming in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) the constitutionality of the doctrine of “separate but equal.” Blacks could be segregated in separate schools, restrooms, and other facilities as long as the facilities were “equal” to those provided for whites. Of course, facilities for blacks rarely proved equal.

Woodrow Wilson brought to the White House southern attitudes toward race and racial segregation. He instituted segregation in the federal workforce, especially the Post Office, and approved segregated drinking fountains and restrooms in the nation’s capital. When critics attacked the policy, Wilson insisted that segregation was “in the interest of the Negro.”

In 1906, a major race riot in Atlanta called into question Booker T. Washington’s strategy of uplift and accommodation. For three days in September, the streets of Atlanta ran red with blood as angry white mobs chased and cornered any blacks they happened upon. An estimated 250 African Americans died in the riots—

Foremost among Washington’s critics stood W. E. B. Du Bois, a Harvard graduate who urged African Americans to fight for civil rights and racial justice. In The Souls of Black Folk (1903), Du Bois attacked the “Tuskegee Machine,” comparing Washington to a political boss who used his influence to silence his critics and reward his followers. Du Bois founded the Niagara movement in 1905, calling for universal male suffrage, civil rights, and leadership composed of a black intellectual elite. The Atlanta riot only bolstered his resolve. In 1909, the Niagara movement helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), a coalition of blacks and whites that sought legal and political rights for African Americans through the courts. In the decades that followed, the NAACP came to represent the future for African Americans, while Booker T. Washington, who died in 1915, represented the past.

REVIEW How did race, class, and gender shape the limits of progressive reform?