The American Promise: Printed Page 626

MAKING HISTORICAL ARGUMENTS

The American Promise: Printed Page 626

Page 626What Did African Americans Want from World War I, and What Did They Get?

When the United States entered the First World War, some black leaders remembered the crucial role that black soldiers had played in the Civil War. They rejoiced that military service would once again offer blacks a chance to demonstrate their patriotism and fitness for full citizenship. Others, however, believed that black Americans had already long ago demonstrated their worth.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) declared that black Americans would support the war but added, “Absolute loyalty in arms and civil duties need not for a moment lead us to abate our just complaints and just demands.” W. E. B. Du Bois, the NAACP’s most outspoken member, urged blacks to “close ranks” in support of the war effort—

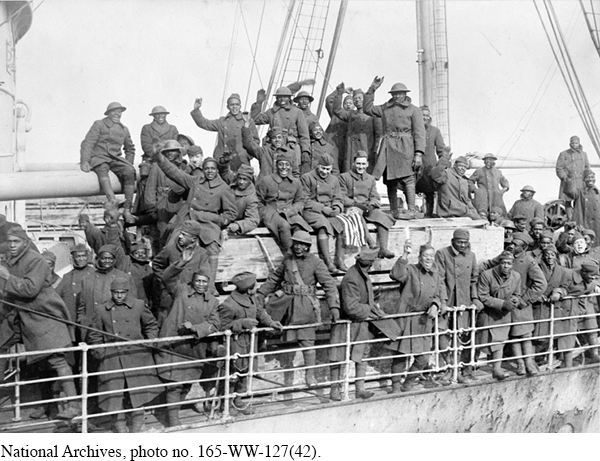

While African Americans remained skeptical about President Wilson’s claim that the United States was fighting to make the world safe for democracy, most nevertheless followed Du Bois’s advice. On the first day of registration for military service, more than 70,000 black men signed in at their draft boards. By war’s end, 370,000 blacks had been inducted, some 31 percent of the total number of blacks registered. The figure for whites was 26 percent.

During training, black recruits discovered that they were rigidly segregated, usually assigned to labor battalions, and faced crude abuse and miserable living conditions. When black soldiers arrived in Europe, white commanders made a point of maintaining American racial standards. A report from the headquarters of the American commander, General John J. Pershing, advised the French that their failure to draw the color line threatened Franco-

Seeking to take advantage of the situation, German propagandists raised some difficult questions. One leaflet distributed to black troops reminded them that they lacked the rights whites enjoyed, were segregated, and sometimes lynched. “Why, then, fight the Germans,” the leaflet asked, “only for the benefit of the Wall Street robbers and to protect the millions they have loaned to the British, French, and Italians?” Why, indeed?

Black soldiers wanted to prove a point. While at first they worked mainly as laborers, before long they had their chance to fight. In February 1918, General Pershing received an urgent call from the French for help on the front lines. Determined not to lose control over the white troops he valued more, Pershing sent black regiments from the 92nd Division. At the front, they were integrated into units of the French army. The black 369th Regiment spent 191 days in battle—

When the battle-

Reasons soon presented themselves. Segregation remained entrenched, and nothing black soldiers did in France persuaded white Americans that race relations should change. Defenders of second-

Even the armed services failed to continue to offer new opportunities. Until the late 1940s, after the next world war, the American military remained not only segregated but almost devoid of black officers. Discrimination extended even beyond the ultimate sacrifice. When organizers of a trip to France for parents of soldiers lost in the First World War announced that the ship would be segregated, black mothers felt honor bound to decline the offer to visit the cemeteries where their sons lay.

Questions for Analysis

Summarize the Argument: What does the author argue that African Americans sought with their participation in the fighting in France during World War I, and what in fact did they gain?

Analyze the Evidence: Why were African Americans so wrong in their expectations? What frustrations did they face during their service, and what policies prevented them from achieving their goals after the war?

Consider the Context: Who else in America saw in the war an opportunity for reform and regeneration? Which of these struggles were successful, and which were disappointed?