The American Promise: Printed Page 642

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 666

BEYOND AMERICA’S BORDERS

The American Promise: Printed Page 642

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 666

Page 642Bolshevism

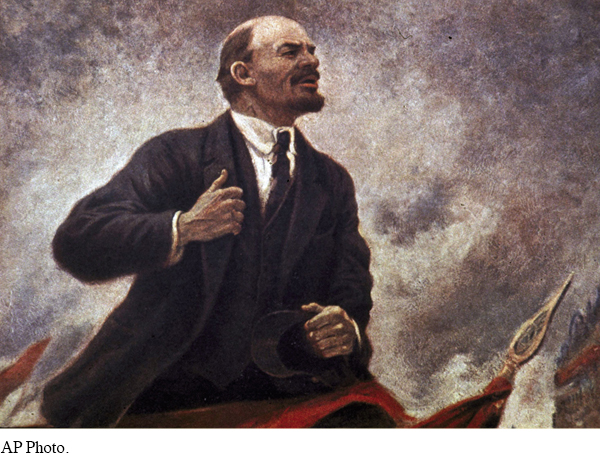

In March 1917, revolutionaries overthrew the Russian czar, whose hereditary rule was the target of peasants and urban workers seeking a more democratic government. But Marxist radicals, who called themselves Bolsheviks, were not satisfied with the regime change. In November, the Bolsheviks seized control of Russia and made their leader, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, ruler. Lenin scoffed at the idea that the Allies were fighting for democracy and insisted that greedy capitalists were waging war for international dominance. In March 1918, he shocked Woodrow Wilson and the Allies by signing a separate peace with Germany and withdrawing Russia from the war. Still locked in the desperate struggle with Germany, the Allies cried betrayal.

The Bolshevik regime dedicated itself to ending capitalism in Russia (known as the Soviet Union after 1922) and to instituting what it called a “dictatorship of the proletariat.” In theory, workers—

Prodded by British leader Winston Churchill, who declared that “the Bolshevik infant should be strangled in its cradle,” Britain and France urged the United States to join them in sending troops to Russia in support of Russian democrats opposing the new revolutionary regime. Several prominent Americans spoke out against American intervention. Senator William Borah of Idaho declared: “The Russian people have the same right to establish a Socialist state as we have to establish a republic.” But Wilson concluded that the Bolsheviks were a dictatorial party that had come to power through a violent coup that denied Russians political choice, and in September 1918 he ordered 14,000 U.S. troops to join British and French forces in Russia. U.S., British, and French troops fought to overthrow Lenin and annul the Bolshevik Revolution, but the Bolsheviks (by now calling themselves Communists) prevailed. U.S. troops withdrew from Russia in June 1919, after the loss of more than 200 American lives.

The Bolshevik regime also committed itself to overthrowing capitalist and imperialist regimes around the world. Clearly, Lenin’s imagined future was at odds with Wilson’s proposed liberal new world order. Wilson withheld U.S. diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union (a policy that persisted until 1934) and joined the Allies in an economic boycott to bring down the Bolshevik government. Unbowed, Lenin promised that his party would “incite rebellion among all the peoples now oppressed,” and revolutionary agitation became central to Soviet foreign policy. Just after the armistice, Communist revolutions erupted in Bavaria and Hungary. Though short-

Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer perceived a “blaze of Revolution sweeping over every American institution of law and order . . . licking the altars of churches . . . crawling into the sacred corners of American homes.” In 1919, the U.S. government launched an all-

The Bolshevik Revolution had endless consequences. In the Soviet Union, it initiated a brutal reign of terror that lasted for more than seven decades. In international politics, it set up a polarity that lasted nearly as long. In a very real sense, the Cold War, which set the United States and the Soviet Union at each other’s throats after World War II, began in 1917. America’s abortive military intervention against the Bolshevik regime and the Bolsheviks’ call for worldwide revolution convulsed relations from the very beginning. In the United States, the rabid antiradicalism of the Red scare threatened traditional American values. Commitment to the protection of dissent succumbed to irrational anticommunism. Even mild reform became tarred with the brush of bolshevism. Although the Red scare quickly withered, the habit of crushing dissent in the name of security would live on. Years later, in the 1950s, when Americans’ anxiety mounted and their confidence waned once again, witch-

Questions for Analysis

Consider the Context: Why did U.S.-Bolshevik relations get off to such a rocky start? Were harsh relations the result of certain policy decisions or inherent in the clashing value systems?

Ask Historical Questions: In the United States, is there an inevitable tension between national security and free expression? Why or why not?

Analyze the Evidence: How did Lenin’s and Wilson’s aspirations for the post–