The American Promise: Printed Page 679

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 620

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 706

Introduction to Chapter 24

The American Promise: Printed Page 679

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 620

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 706

Page 67924

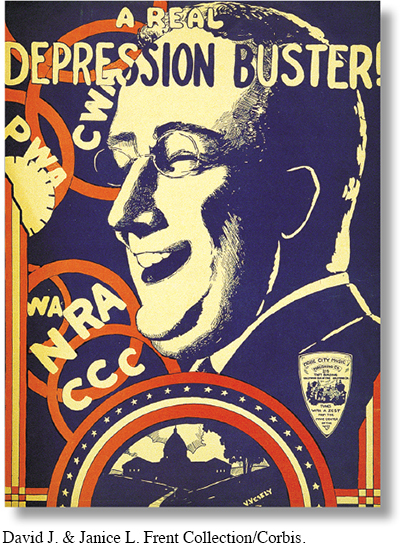

The New Deal Experiment

1932–

CONTENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Explain which issues shaped the presidential campaign of 1932 and how the candidates’ strategies differed. Determine the significance of Roosevelt’s victory.

Analyze which factors united New Deal reformers and what kinds of policies they endorsed. Describe the initial reforms enacted during Roosevelt’s first one hundred days in office.

Recount why critics resisted the New Deal.

Explain how the Second New Deal moved the country toward a welfare state and describe the kinds of programs reformers proposed. Evaluate why some Americans were left out of the New Deal.

Identify the final phase of the New Deal and why it ultimately reached a deadlock.

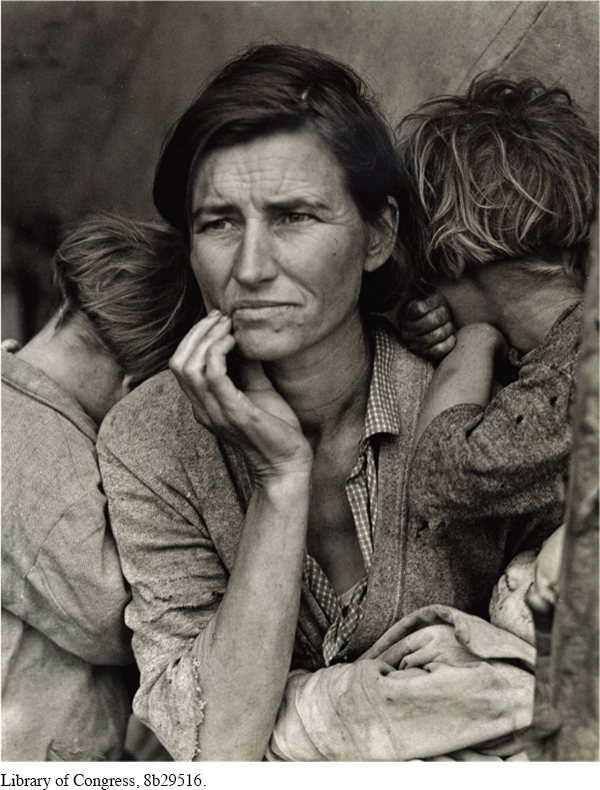

IN MARCH 1936, FLORENCE OWENS PILED HER SEVEN children into her old Hudson. They had been picking beets in southern California, near the Mexican border, but the harvest was over now. Owens headed north, where she hoped to find work picking lettuce. About halfway there, her car broke down. She coasted into a labor camp of more than two thousand migrant workers who were hungry and out of work. They had been attracted by advertisements of work in the pea fields, only to find the crop ruined by a heavy frost. Owens set up a lean-

Florence Owens was born in 1903 in Oklahoma, then Indian Territory. Both of Florence’s parents were Cherokee. When she was seventeen, Florence married Cleo Owens, a farmer who moved his growing family to California, where he worked in sawmills. Cleo died of tuberculosis in 1931, leaving Florence a widow with six young children.

The American Promise: Printed Page 679

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 620

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 706

Page 680Florence began to work as a farm laborer in California’s Central Valley to support herself and her children. She picked cotton, earning about $2 a day. “I’d leave home before daylight and come in after dark,” she explained. “We just existed!” To survive, she worked nights as a waitress, making “50-

Like tens of thousands of other migrant laborers, Owens followed the crops, planting, cultivating, and harvesting as jobs opened up in the fields along the West Coast from California to Oregon and Washington. Joining Owens and other migrants—

Soon after Florence Owens fed her children at the pea pickers’ camp, a car pulled up, and a woman with a camera got out and began to take photographs of Owens. The woman was Dorothea Lange, a photographer employed by a New Deal agency to document conditions among farmworkers in California. Lange snapped six photos of Owens, and climbed back in her car and headed to Berkeley. Owens and her family, their car now repaired, drove off to look for work in the lettuce fields.

Lange’s last photograph of Owens, subsequently known as Migrant Mother, became an icon of the desperation among Americans that President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal sought to alleviate. While Migrant Mother became Dorothea Lange’s most famous photograph, Florence Owens continued to work in the fields, “ragged, hungry, and broke,” as a San Francisco newspaper noted.

Unlike Owens, her children, and other migrant workers, many Americans received government help from Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives to provide relief for the needy, to speed economic recovery, and to reform basic economic and governmental institutions. Roosevelt’s New Deal elicited bitter opposition from critics on the right and the left, and it failed to satisfy fully its own goals of relief, recovery, and reform. But within the Democratic Party, the New Deal energized a powerful political coalition that helped millions of Americans withstand the privations of the Great Depression. In the process, the federal government became a major presence in the daily lives of most American citizens.

The American Promise: Printed Page 679

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 620

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 706

Page 681CHRONOLOGY

| 1933 |

|

| 1934 |

|

| 1935 |

|

| 1936 |

|

| 1937 |

|

| 1938 |

|