The American Promise: Printed Page 686

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 626

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 713

Banking and Finance Reform

Roosevelt wasted no time making good on his inaugural pledge for “action now.” As he took the oath of office on March 4, the nation’s banking system was on the brink of collapse. Roosevelt immediately devised a plan to shore up banks and restore depositors’ confidence. Working round the clock, New Dealers drafted the Emergency Banking Act, propped up the private banking system with federal funds, and subjected banks to federal regulation and oversight. To secure the confidence of depositors, Congress passed the Glass-

On Sunday night, March 12, while the banks were still closed, Roosevelt broadcast the first of a series of fireside chats. Speaking in a friendly, informal manner, he explained the new banking legislation that, he said, made it “safer to keep your money in a reopened bank than under the mattress.” With such plain talk, Roosevelt translated complex matters into common sense. This and subsequent fireside chats forged a direct connection—

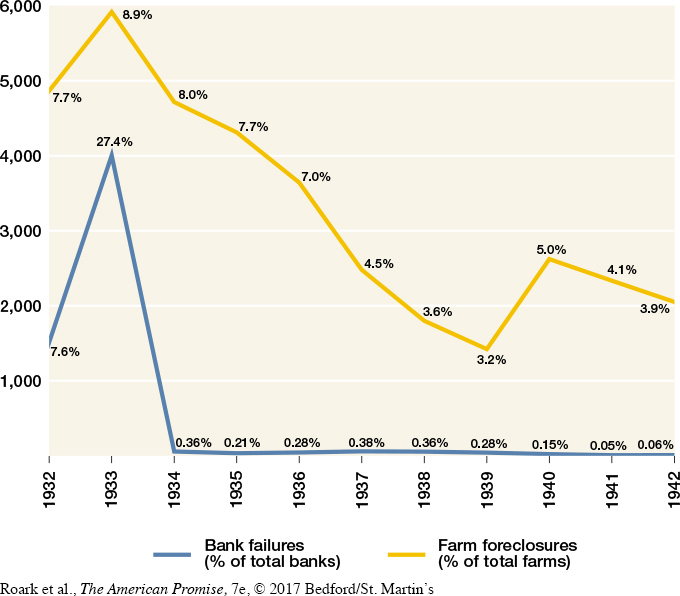

The banking legislation and fireside chat worked. Within a few days, most of the nation’s major banks reopened, and they remained solvent as reassured depositors switched funds from their mattresses to their bank accounts (Figure 24.1). One New Dealer boasted, “Capitalism was saved in eight days.” The rescue of the banking system took much longer to succeed, though.

The American Promise: Printed Page 686

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 626

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 713

Page 687In his inaugural address, Roosevelt criticized financiers for their greed and incompetence. To prevent the fraud, corruption, and insider trading that had tainted Wall Street and contributed to the crash of 1929, New Dealers created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 1934 to oversee financial markets by licensing investment dealers, monitoring all stock transactions, and requiring corporate officers to make full disclosures about their companies. To head the SEC, Roosevelt appointed an ambitious Wall Street financier, Joseph P. Kennedy (father of the future president John F. Kennedy), who had a shady reputation for stock manipulation. Under Kennedy’s leadership, the SEC helped clean up and regulate Wall Street, which slowly recovered.