The American Promise: Printed Page 694

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 631

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 719

Casualties in the Countryside

The AAA weathered critical battering by champions of the old order better than the NRA. Allotment checks for keeping land fallow and crop prices high created loyalty among farmers with enough acreage to participate. As a white farmer in North Carolina declared, “I stand for the New Deal and Roosevelt . . . , the AAA . . . and crop control.”

Protests stirred, however, among those who did not qualify for allotments. The Southern Farm Tenants Union argued passionately that the AAA enriched large farmers while it impoverished small farmers who rented rather than owned their land. One black sharecropper explained why only $75 a year from New Deal agricultural subsidies trickled down to her: “De landlord is landlord, de politicians is landlord, de judge is landlord, de shurf [sheriff] is landlord, ever’body is landlord, en we [sharecroppers] ain’ got nothin’!” Like the NRA, the AAA tended to help most those who least needed help. Roosevelt’s political dependence on southern Democrats caused him to avoid confronting economic and racial inequities in the South.

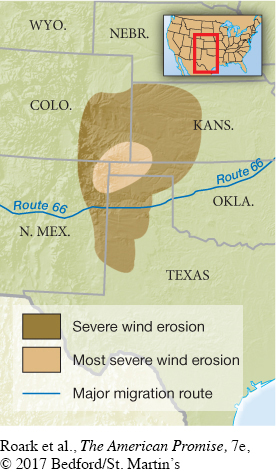

Displaced tenants often joined the army of migrant workers like Florence Owens who straggled across rural America during the 1930s, some to flee Great Plains dust storms. Many migrants came from Mexico to work Texas cotton, Michigan beans, Idaho sugar beets, and California crops of all kinds. But since the number of people willing to take agricultural jobs usually exceeded the number of jobs available, wages fell and native-