The American Promise: Printed Page 697

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 635

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 723

Relief for the Unemployed

First and foremost, Americans still needed jobs. Since the private economy left eight million people jobless by 1935, Roosevelt and his advisers launched a massive work relief program. Roosevelt believed that direct government handouts crippled recipients with “spiritual and moral disintegration . . . destructive to the human spirit.” Jobs, by contrast, bolstered individuals’ “self-

By 1936, WPA funds provided jobs for 7 percent of the nation’s labor force. In effect, the WPA made the federal government the employer of last resort, creating useful jobs when the capitalist economy failed to do so. In hiring, WPA officials tended to discriminate in favor of white men and against women and racial minorities. Still, the WPA made major contributions to both relief and recovery, putting thirteen million men and women to work earning paychecks worth $10 billion. (See “Analyzing Historical Evidence: Americans Encounter the New Deal.”)

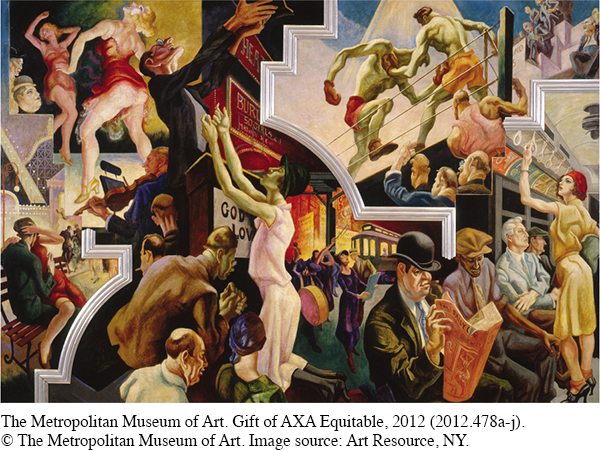

About three out of four WPA jobs involved construction and renovation of the nation’s physical infrastructure. WPA workers built 572,000 miles of roads, 78,000 bridges, 67,000 miles of city streets, 40,000 public buildings, and much else. In addition, the WPA gave jobs to thousands of artists, musicians, actors, journalists, poets, and novelists. The WPA also organized sewing rooms for jobless women, giving them work and wages. These sewing rooms produced more than 100 million pieces of clothing that were donated to the needy. Throughout the nation, WPA projects displayed tangible evidence of the New Deal’s commitment to public welfare.