The American Promise: Printed Page 718

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 656

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 747

Japan Attacks America

Although the likelihood of war with Germany preoccupied Roosevelt, Hitler exercised a measure of restraint in directly provoking America. Japanese ambitions in Asia clashed more openly with American interests and commitments, especially in China and the Philippines. And unlike Hitler, the Japanese high command planned to attack the United States in order to pursue Japan’s aspirations to rule an Asian empire it termed the Greater East Asia Co-

The American Promise: Printed Page 718

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 656

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 747

Page 719

In 1940, Japan signaled a new phase of its imperial designs by entering a defensive alliance with Germany and Italy—

The American Promise: Printed Page 718

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 656

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 747

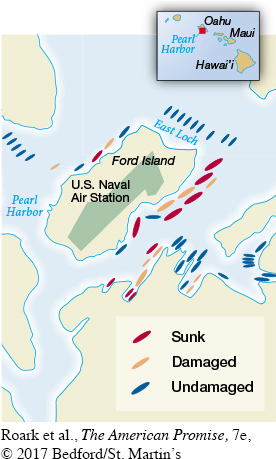

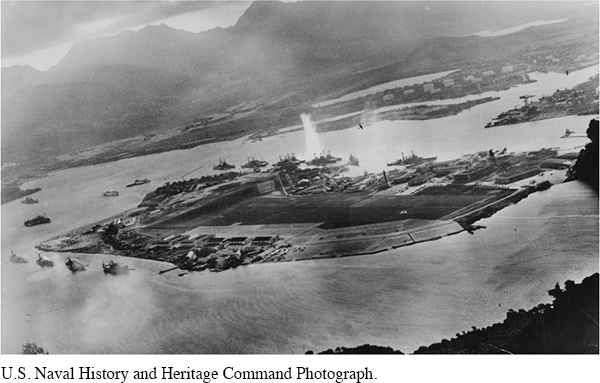

Page 720Instead, the American embargo played into the hands of Japanese militarists headed by General Hideki Tojo, who seized control of the government in October 1941 and persuaded other leaders, including Emperor Hirohito, that swift destruction of American naval bases in the Pacific would leave Japan free to follow its destiny. On December 7, 1941, 183 aircraft lifted off six Japanese carriers and attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on the Hawai’ian island of Oahu. The devastating surprise attack sank all of the fleet’s battleships, killed more than 2,400 Americans, and almost crippled U.S. war-

The Japanese scored a stunning tactical victory at Pearl Harbor, but in the long run the attack proved a colossal blunder. The victory made many Japanese commanders overconfident about their military prowess. Worse for the Japanese, Americans instantly united in their desire to fight and avenge the attack. Roosevelt vowed that “this form of treachery shall never endanger us again.” On December 8, Congress endorsed the president’s call for a declaration of war. Both Hitler and Mussolini declared war against America on December 11, bringing the United States into all-

REVIEW How did Roosevelt attempt to balance American isolationism with the military aggression of Germany and Japan in the late 1930s and early 1940s?