The American Promise: Printed Page 725

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 660

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 750

Conversion to a War Economy

The American Promise: Printed Page 725

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 660

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 750

Page 725In 1940, the American economy remained mired in the depression. Nearly one worker in seven was still unemployed, factories operated far below their productive capacity, and the total federal budget was less than $10 billion. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt announced the goal of converting the economy to produce “overwhelming . . . , crushing superiority of equipment in any theater of the world war.” Factories were converted to assembling tanks and airplanes, and production soared to record levels. By the end of the war, jobs exceeded workers, plants operated at full capacity, and the federal budget topped $100 billion.

To organize and oversee this tidal wave of military production, Roosevelt called upon business leaders to come to Washington and, for the token payment of a dollar a year, head new government agencies such as the War Production Board, which set production priorities and pushed for maximum output. Contracts flowed to large corporations, often on a basis that guaranteed their profits. During the first half of 1942, the government issued contracts worth more than the entire gross national product in 1941.

Booming wartime employment swelled union membership. To speed production, the government asked unions to pledge not to strike. Despite the relentless pace of work, union members mostly kept their no-

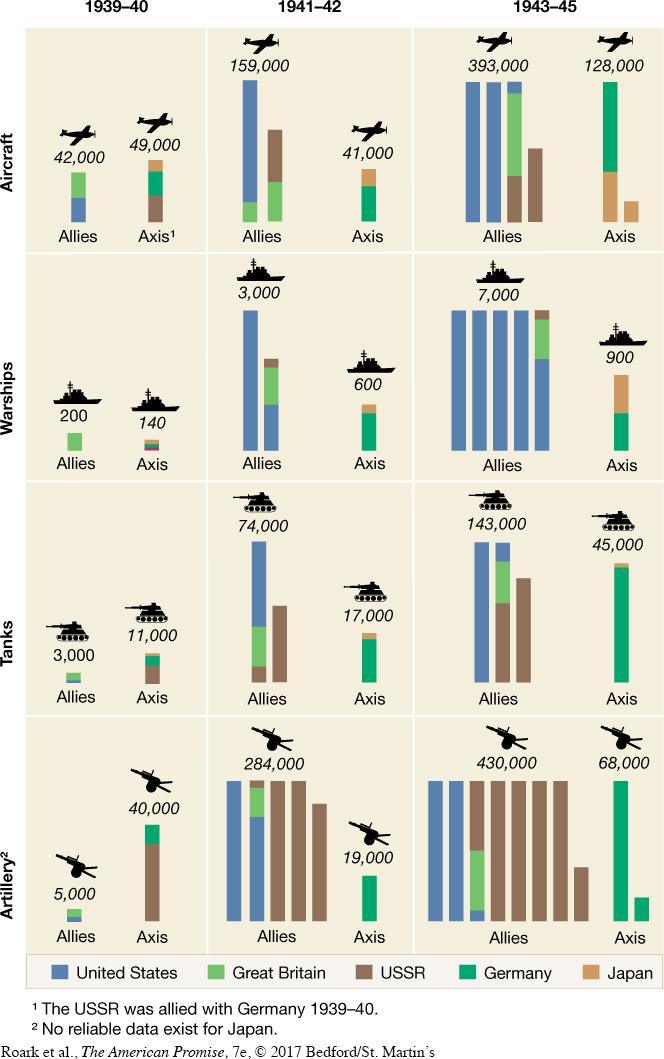

Overall, conversion to war production achieved Roosevelt’s ambitious goal of “crushing superiority” in military goods. At a total cost of $304 billion (equivalent to about $4 trillion today) during the war, the nation produced an avalanche of military equipment, more than double the combined production of Germany, Japan, and Italy (Figure 25.1). This outpouring of military goods supplied not only U.S. forces but also America’s allies, giving tangible meaning to Roosevelt’s pledge to make America the “arsenal of democracy.”

REVIEW How did the Roosevelt administration mobilize the human and industrial resources necessary to fight a two-