The American Promise: Printed Page 715

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 653

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 743

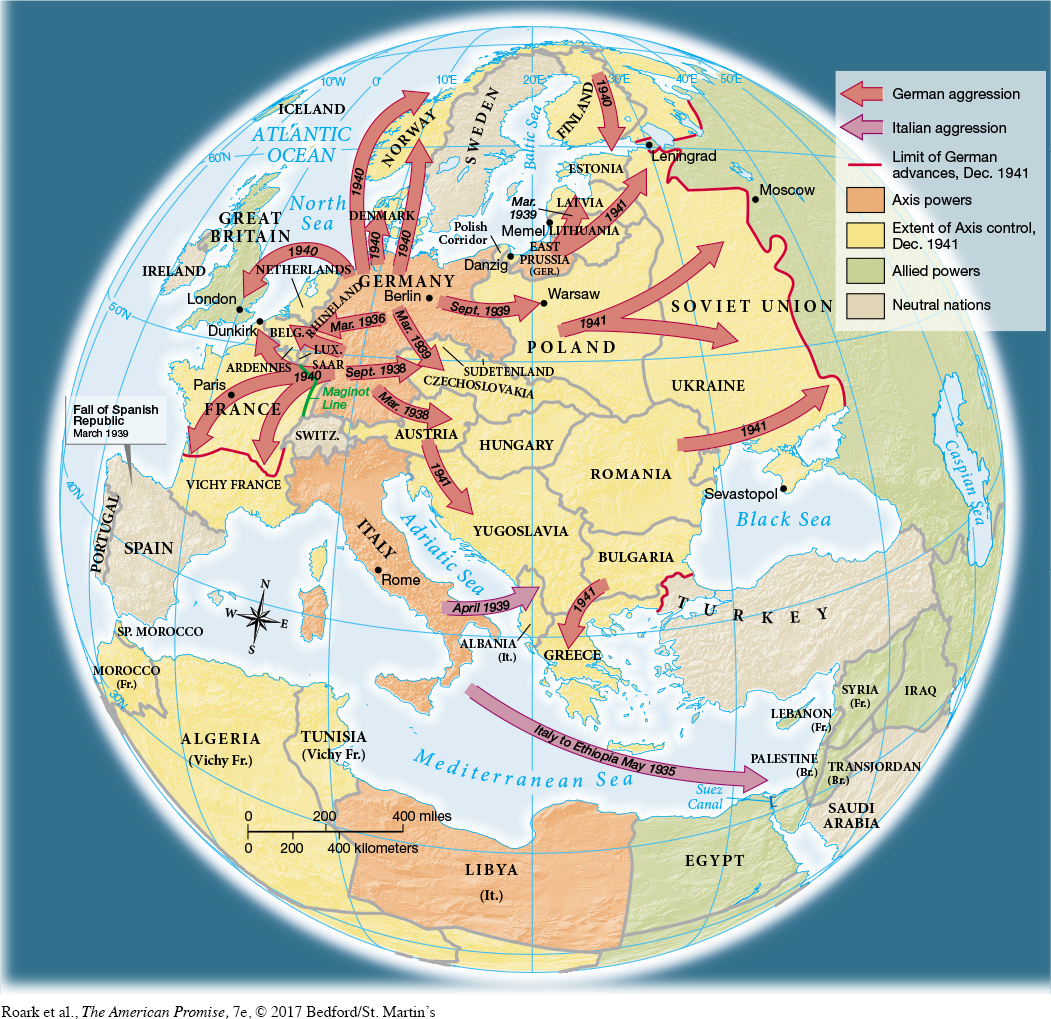

Nazi Aggression and War in Europe

Under the spell of isolationism, Americans passively watched Hitler’s relentless campaign to dominate Europe (Map 25.1). In 1938, Hitler incorporated Austria into Germany and turned his attention to Sudetenland, which had been granted to Czechoslovakia by the World War I peace settlement. Hoping to avoid war, British prime minister Neville Chamberlain offered Hitler terms of appeasement that would give the Sudetenland to Germany if Hitler agreed to leave the rest of Czechoslovakia alone. Hitler accepted the terms but did not keep his promise. By 1939, Hitler had annexed Czechoslovakia and demanded that Poland return the German territory it had gained after World War I. Recognizing that appeasement of Hitler had failed, Britain and France assured Poland that they would go to war with Germany if Hitler attacked. In turn, Hitler negotiated with his bitter enemy, Soviet premier Joseph Stalin, offering him concessions to prevent the Soviet Union from joining Britain and France in opposing a German attack on Poland. Despite the enduring hatred between fascist Germany and the Communist Soviet Union, the two powers signed the Nazi-

The American Promise: Printed Page 715

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 653

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 743

Page 716The American Promise: Printed Page 715

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 653

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 743

Page 717At dawn on September 1, 1939, Hitler unleashed his blitzkrieg (literally, “lightning war”) on Poland. “Act brutally!” Hitler exhorted his generals. “Send [every] man, woman, and child of Polish descent and language to their deaths, pitilessly and remorselessly.” The attack triggered Soviet attacks on eastern Poland and declarations of war from France and Britain two days later, igniting a conflagration that raced around the globe. In September 1939, Germany seemed invincible, causing many people to fear that all of Europe would soon share Poland’s fate.

After the Nazis overran Poland, Hitler soon launched a westward blitzkrieg. In the first six months of 1940, German forces smashed through Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. The speed of the German attack trapped more than 300,000 British and French soldiers, who retreated to the port of Dunkirk, where an improvised armada of British vessels ferried them to safety across the English Channel. By mid-

The new British prime minister, Winston Churchill, vowed that Britain, unlike France, would never surrender to Hitler. “We shall fight on the seas and oceans [and] . . . in the air,” he proclaimed, “whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, . . . and in the fields and in the streets.” Churchill’s defiance stiffened British resolve against Hitler’s attack, which began in mid-