The American Promise: Printed Page 790

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 715

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 815

Consumption Rules the Day

Scorned by Khrushchev during the kitchen debate as unnecessary gadgets, consumer items flooded American society in the 1950s. Although the purchase and display of consumer goods was not new (see “Consumer Culture” in chapter 23), at midcentury consumption had become a reigning value, vital for economic prosperity and essential to individuals’ identity and status. In place of the traditional emphasis on work and savings, the consumer culture encouraged satisfaction and happiness through the acquisition of new products.

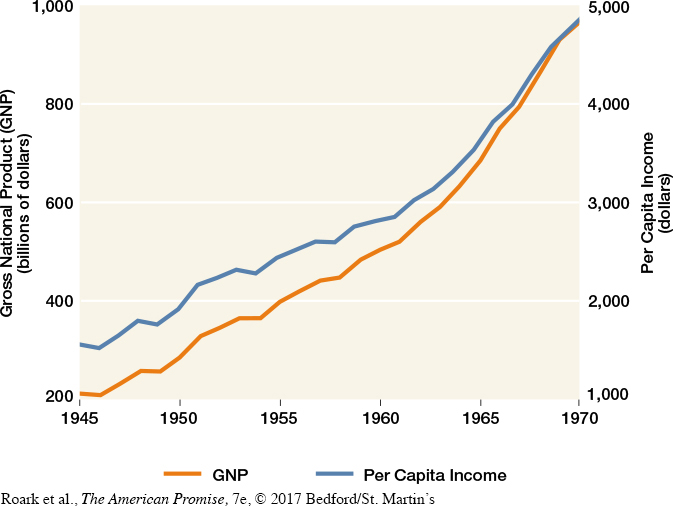

The consumer culture rested on a firm material base. Between 1950 and 1960, both the gross national product (the value of all goods and services produced) and median family income grew by 25 percent in constant dollars (Figure 27.1). Economists claimed that 60 percent of Americans enjoyed middle-

Several forces spurred this unparalleled abundance. A population surge—

Although the sheer need to support themselves and their families motivated most women’s employment, a desire to secure some of the new abundance sent growing numbers of women to work. As one woman remarked, “My Joe can’t put five kids through college . . . and the washer had to be replaced, and Ann was ashamed to bring friends home because the living room furniture was such a mess, so I went to work.” The standards for family happiness imposed by the consumer culture increasingly required a second income.