The American Promise: Printed Page 792

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 717

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 818

Countercurrents

Pockets of dissent underlay the conventionality of the 1950s. Some intellectuals took exception to the materialism and conformity of the era. In The Lonely Crowd (1950), sociologist David Riesman lamented a shift from the “inner-

Implicit in much of the critique of consumer culture was concern about the loss of traditional masculinity. Consumption was associated with women and their presumed greater susceptibility to manipulation. Men, required to conform to get ahead, moved further away from the masculine ideals of individualism and aggressiveness. Moreover, the increase in married women’s employment compromised the male ideal of breadwinner. Into this gender confusion came Playboy, which began publication in 1953 and quickly gained a circulation of one million. The new magazine idealized masculine independence in the form of bachelorhood and assaulted the middle-

In fact, two books published by Alfred Kinsey and other researchers at Indiana University—

The American Promise: Printed Page 792

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 717

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 818

Page 793Less direct challenges to mainstream standards appeared in the everyday behavior of young Americans. “Roll over Beethoven and tell Tchaikovsky the news!” belted out Chuck Berry in his 1956 hit record celebrating rock and roll, a new form of music that combined country with black rhythm and blues. White teenagers lionized Elvis Presley, who shocked their parents with his tight pants, hip-

The most blatant revolt against conventionality came from the self-

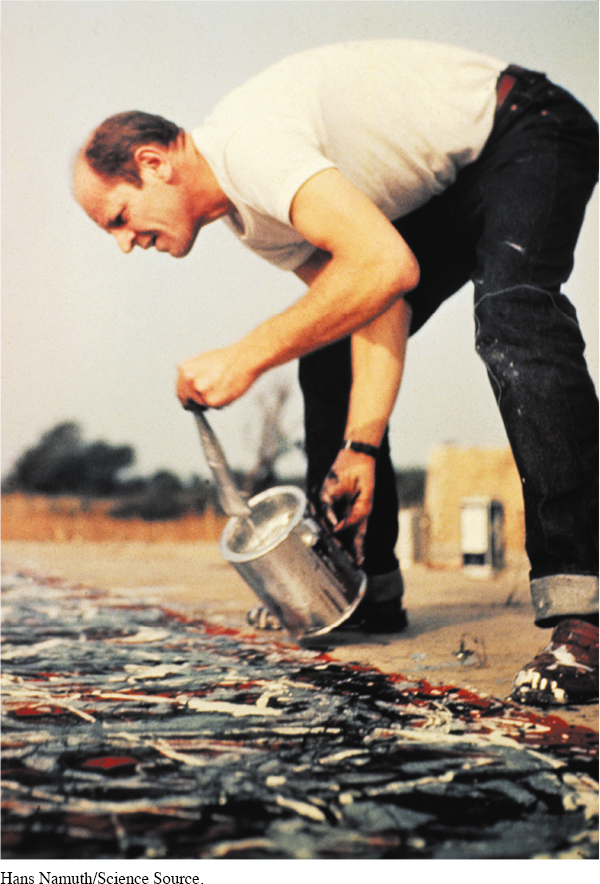

Bold new styles in the visual arts also showed the 1950s to be more than a decade of bland conformity. In New York City, “action painting” or “abstract expressionism” flowered, rejecting the idea that painting should represent recognizable forms. Jackson Pollock and other abstract expressionists poured, dripped, and threw paint on canvases or substituted sticks and other implements for brushes. The new form of painting so captivated and redirected the Western art world that New York replaced Paris as its center.

REVIEW Why did American consumption expand so dramatically in the 1950s, and what aspects of society and culture did it influence?