The American Promise: Printed Page 812

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 736

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 840

The Response in Washington

Civil rights leaders would have to wear sneakers, Lyndon Johnson said, if they were going to keep up with him. But both Kennedy and Johnson, reluctant to alienate southern voters and their congressional representatives, tended to move only when events gave them little choice. In June 1963, Kennedy finally made good on his promise to seek strong antidiscrimination legislation. Pointing to the injustice suffered by blacks, Kennedy asked white Americans, “Who among us would then be content with the counsels of patience and delay?” Johnson took up Kennedy’s commitment with passion, as scenes of violence against peaceful demonstrators appalled television viewers across the world. The resulting public support, the “Johnson treatment,” and the president’s appeal to memories of the martyred Kennedy all produced the most important civil rights law since Reconstruction.

The American Promise: Printed Page 812

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 736

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 840

Page 813The Civil Rights Act of 1964 guaranteed access for all Americans to public accommodations, public education, employment, and voting, and it extended constitutional protections to Indians on reservations. Title VII of the measure, banning discrimination in employment, not only attacked racial discrimination but also outlawed discrimination against women. Because Title VII applied to every aspect of employment, including wages, hiring, and promotion, it represented a giant step toward equal employment opportunity for white women as well as for racial minorities.

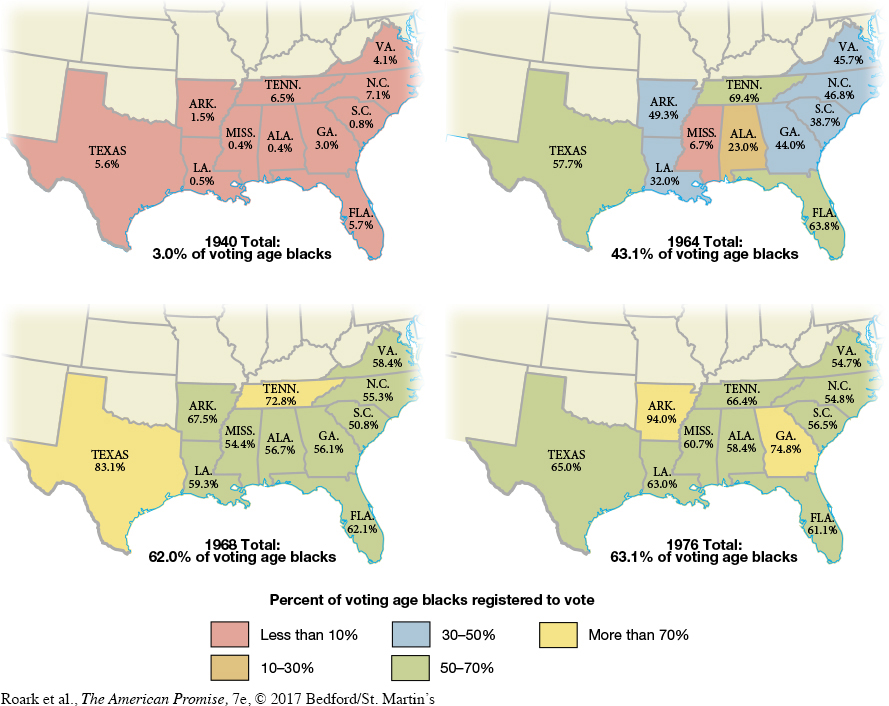

Responding to voter registration drives in the South, Johnson demanded legislation to remove “every remaining obstacle to the right and the opportunity to vote.” In August 1965, he signed the Voting Rights Act, empowering the federal government to intervene directly to enable African Americans to register and vote, thereby launching a major transformation in southern politics. Black voting rates shot up dramatically (Map 28.2). In turn, the number of African Americans holding political office in the South increased from a handful in 1964 to more than a thousand by 1972. Such gains translated into tangible benefits as black officials upgraded public facilities, police protection, and other basic services for their constituents. (See “Making Historical Arguments: What Difference Did the Voting Rights Act Make?”)

Johnson also declared the need to realize “not just equality as a right and theory, but equality as fact and result.” To this end, he issued an executive order in 1965 requiring employers holding government contracts (affecting about one-

The American Promise: Printed Page 812

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 736

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 840

Page 814In 1968, Johnson maneuvered one final bill through Congress. While those in other regions often applauded the gains made by the black freedom struggle in the South, whites were just as likely to resist claims for racial justice in their own locations. In 1963, California voters rejected a law passed by the legislature banning discrimination in housing. And when Martin Luther King Jr. launched a campaign against de facto segregation in Chicago in 1966, thousands of whites jeered and threw stones at demonstrators. Johnson’s efforts to get a federal open-