The American Promise: Printed Page 866

EXPERIENCING THE AMERICAN PROMISE

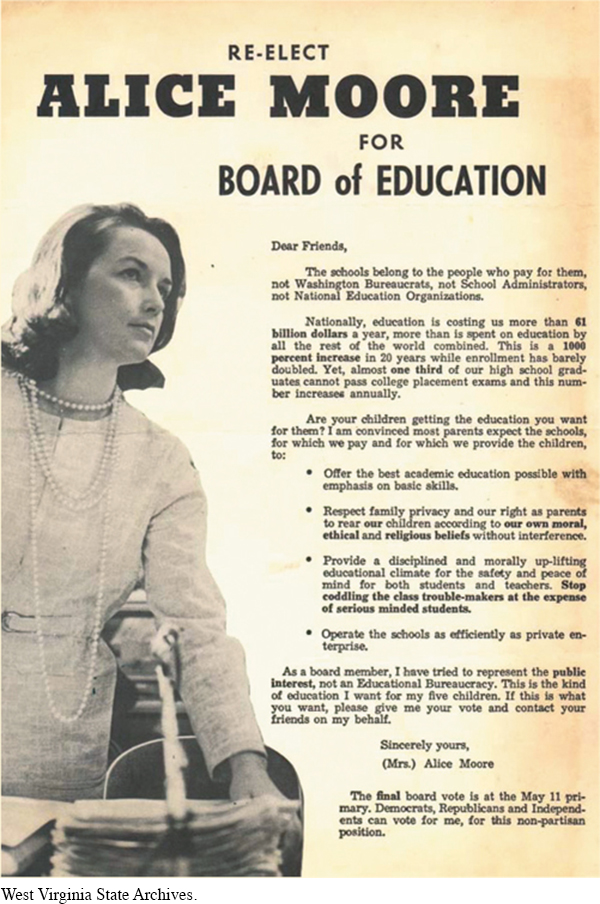

A Mother Campaigns for a Say in Her Children’s Education

Although historians usually trace the rise of conservatism through national politics, the most intense political battles of the 1970s and 1980s often raged at the local level. None were more impassioned than those mounted by parents over what their children should be taught in public schools. The introduction of sex education and new textbooks in the Kanawha County, West Virginia, school district in 1969 prompted Alice Moore to challenge instruction she deemed harmful to her children and to organize a parents’ movement to gain control over their children’s education.

The sprawling school district of Kanawha County encompassed the state capital of Charleston as well as surrounding towns and rural areas containing chemical plants, coal mines, and small hamlets. Alice Moore, a native of Mississippi, and her husband, a fundamentalist minister, lived in a small town on the outskirts of Charleston, where their four children attended local schools. Her disgust with the sex education program prompted her to run for the school board in 1970, and she won a seat as the only woman on a five-

The district’s adoption of a new English language arts curriculum in 1974 provoked even greater controversy. The program, similar to those gaining adoption across the country, sought to teach children about the larger world, incorporated writings by African Americans and other minority groups, and encouraged students to think critically and independently.

Objecting to both the philosophy and the content of the new curriculum, Moore began to mobilize opposition, calling on fundamentalist ministers and holding meetings in churches. In June 1974, at a meeting before an impassioned crowd of more than a thousand, she persuaded the school board to eliminate 8 of the curriculum’s 325 books but failed to prevent adoption of the curriculum by a vote of three to two. Opponents then redoubled their efforts, echoing concerns that were energizing the Christian Right across the country.

Protesters charged that the new materials in the curriculum constituted an assault on Christianity, authority, patriotism, and the system of free enterprise. One of Moore’s allies, a conservative chemical company owner, vilified the curriculum as “liberal, socialist, even communist-

Furthermore, Moore and her supporters objected to the curriculum’s multicultural materials, designed to illustrate the diversity of American society. They disliked the nonstandard English that appeared in some of the literature, as well as what they considered the “trashy” aspects of urban ghetto life. “Why the hell do we have to indoctrinate our children out here in semi-

The new sexual permissiveness of the 1960s also aroused anti-

Such deeply held beliefs inspired opponents to keep their children home when school opened in September, achieving a 20 percent absentee rate. Defying their union leadership, thousands of miners went out on a sympathy strike while protesters set up picket lines and staged demonstrations. Three schools were bombed, district headquarters were dynamited, and guns were fired on both sides. Anti-

The school board ended up keeping most of the new curriculum, but parents were allowed to designate those books they did not want their children to read. Many teachers avoided hassles by not using any of the new books. The board also set new guidelines for choosing textbooks, which included banning materials that contained profanity, that looked favorably on different forms of government, or that “intrude[d] into the privacy of students’ homes by asking personal questions about the inner feelings or behavior of themselves or their parents.”

Conflicts over public school curricula, involving such topics as evolution, continued to strike communities throughout the nation, although none equaled the war in Kanawha County. Some conservative parents retreated from the public schools entirely. By 2013, parents were homeschooling 1.7 million children, and the number of private Christian schools soared, accommodating parents who, in Moore’s words, “can’t put their children in public schools and allow them to have their beliefs torn away.” Those who believed that students should be exposed to a diversity of ideas to form their own beliefs were in the majority, but Christian conservatives such as Moore continued to fight for control over what their children were taught.

Questions for Analysis

Analyze the Evidence: What specific features of the new English language arts curriculum did Alice Moore and her supporters object to?

Recognize Viewpoints: What values of the new conservatives were reflected in the anti-

Consider the Context: What larger tensions of the 1970s did the textbook fight reflect?