The American Promise: Printed Page 911

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 826

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 942

The Globalization of Terrorism

The American Promise: Printed Page 911

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 826

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 942

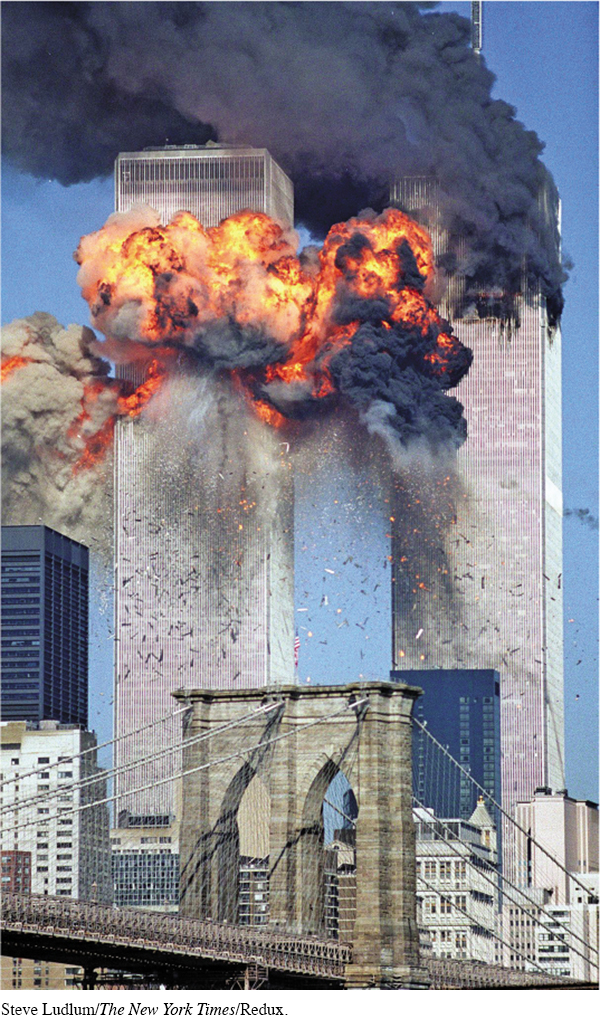

Page 911The response to Hurricane Katrina contrasted sharply with the government’s decisive reaction to the horror that had unfolded four years earlier on the morning of September 11, 2001. Nineteen terrorists hijacked four planes and flew two of them into the twin towers of New York City’s World Trade Center and one into the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.; the fourth crashed in a field in Pennsylvania. The attacks took nearly 2,800 lives, including people from ninety different countries.

The hijackers belonged to Osama bin Laden’s Al Qaeda international terrorist network. Organized in Afghanistan then ruled by the radical Muslim Taliban government, the attacks expressed Islamic extremists’ rage at the spread of Western culture and values into the Muslim world, as well as their opposition to the 1991 Persian Gulf War against Iraq and the stationing of American troops in Saudi Arabia. Bin Laden sought to rid the Middle East of Western influence and install puritanical Muslim control.

The 9/11 terrorists and others who came after them ranged from poor to well-

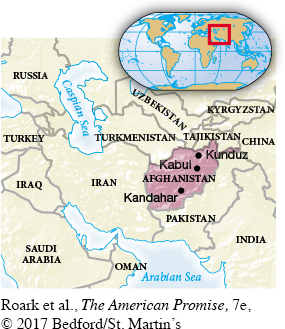

In the wake of the September 11 attacks, President Bush sought a global alliance against terrorism and won at least verbal support from most governments. On October 11, with NATO support, the United States and Britain began bombing Afghanistan, and American forces aided the Northern Alliance, the Taliban government’s main opposition. By December, the Taliban government was destroyed, but bin Laden eluded capture until U.S. special forces killed him in Pakistan in 2011. Afghans elected a new national government, but the Taliban remained strong in large parts of the country and contributed to ongoing economic instability and insecurity. When the Taliban retook the city of Kunduz in 2015, a U.S. soldier who had fought there wrote, “You wonder what all that effort and sacrifice was for.”

The American Promise: Printed Page 911

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 826

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 942

Page 912After the September 11 attacks, anti-

In October 2001, Congress passed the USA Patriot Act, giving the government new powers to monitor suspected terrorists, including the ability to access all Americans’ personal information. It soon provoked calls for revision from both conservatives and liberals. Kathleen MacKenzie, a councilwoman in Ann Arbor, Michigan, explained why the council opposed the Patriot Act: “As concerned as we were about national safety, we felt that giving up [rights] was too high a price to pay.” A security official countered, “If you don’t violate someone’s human rights some of the time, you probably aren’t doing your job.” A decade past 9/11, the government continued to gather personal information on individual citizens, seeming to some to have sacrificed too much liberty for security.

Insisting that presidential powers were virtually limitless in times of national crisis, Bush stretched his authority until he met resistance from the courts and Congress. The United States detained more than 700 prisoners captured in Afghanistan and taken to the U.S. military base at Guantánamo, Cuba, where, until the courts acted, they had no rights and were sometimes tortured. Although President Barack Obama promised to close the detention camp, he met resistance from Congress, and more than fifty prisoners remained there in 2016.

The government also sought to protect Americans from future terrorist attacks through the greatest reorganization of the executive branch since 1948. In November 2002, Congress authorized the new Department of Homeland Security, combining 170,000 federal employees from twenty-