The American Promise: Printed Page 897

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 813

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 927

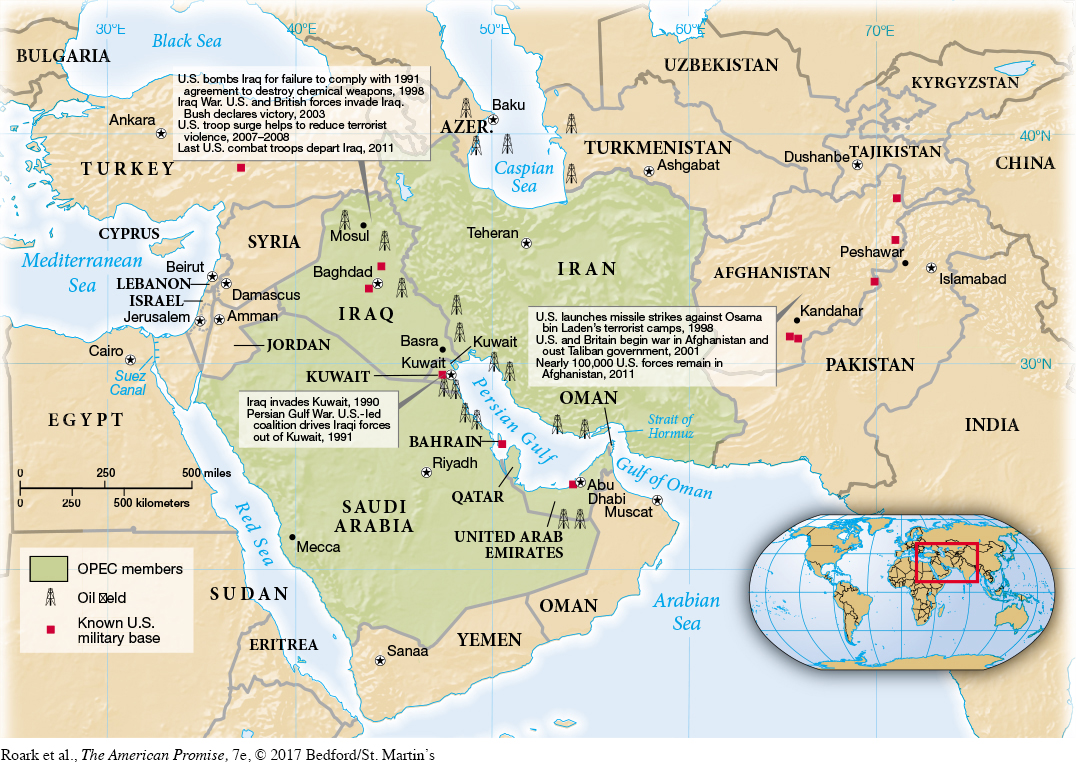

Going to War in Central America and the Persian Gulf

Near its borders, the United States continued to exercise its military power. In Central America, U.S. officials had supported Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, whom they valued for his anticommunism. But in 1989, after an American grand jury indicted Noriega for drug trafficking and after his troops killed an American Marine, Bush ordered 25,000 military personnel into Panama to capture him. U.S. forces quickly overcame Noriega’s troops, sustaining 23 deaths, while hundreds of Panamanians, including many civilians, died. Colin Powell noted that “our euphoria over our victory was not universal.” Both the United Nations and the Organization of American States condemned the unilateral action by the United States.

By contrast, Bush’s second military engagement rested solidly on international approval. Viewing Iran as America’s major enemy in the Middle East, U.S. officials had quietly assisted the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein in the Iran-

The American Promise: Printed Page 897

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 813

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 927

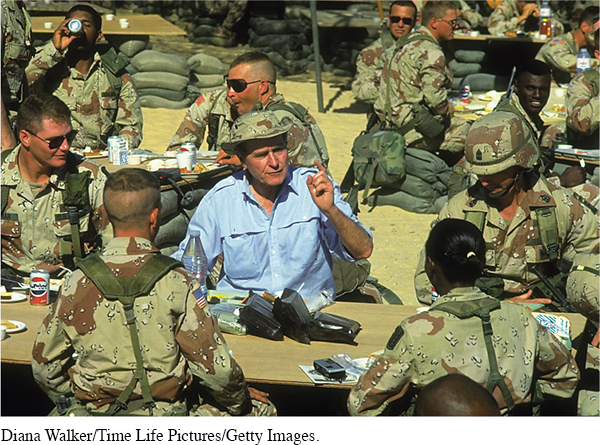

Page 898Reflecting the easing of Cold War tensions, the Soviet Union supported a UN embargo on Iraqi oil and authorization for using force if Iraq did not withdraw from Kuwait by January 15, 1991. By then, the United States had deployed more than 400,000 soldiers to Saudi Arabia, joined by 265,000 troops from two dozen other nations, including several Arab states. “The community of nations has resolutely gathered to condemn and repel lawless aggression,” Bush announced. “With few exceptions, the world now stands as one.”

When the UN-

The American Promise: Printed Page 897

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 813

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 927

Page 899“By God, we’ve kicked the Vietnam syndrome once and for all,” President Bush exulted on March 1. Most Americans found no moral ambiguity in the Persian Gulf War and took pride in the display of military prowess. The United States stood at the apex of global leadership, steering a coalition in which Arab nations fought beside their former colonial rulers.

Some Americans wondered why Bush ended the war without deposing Hussein. Bush pointed to the limited UN mandate and to Middle Eastern leaders’ concerns that invading Iraq would destabilize the region. His secretary of defense, Richard Cheney, doubted that a stable government could be created to replace Hussein and considered the price of a long occupation too high. Instead, administration officials counted on Hussein’s pledge not to rearm or develop weapons of mass destruction, secured by a system of UN inspections, to contain him.

After the war, Israel, which had endured Iraqi missile attacks, was more secure, but the Israeli-