The American Promise: Printed Page 123

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 115

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 133

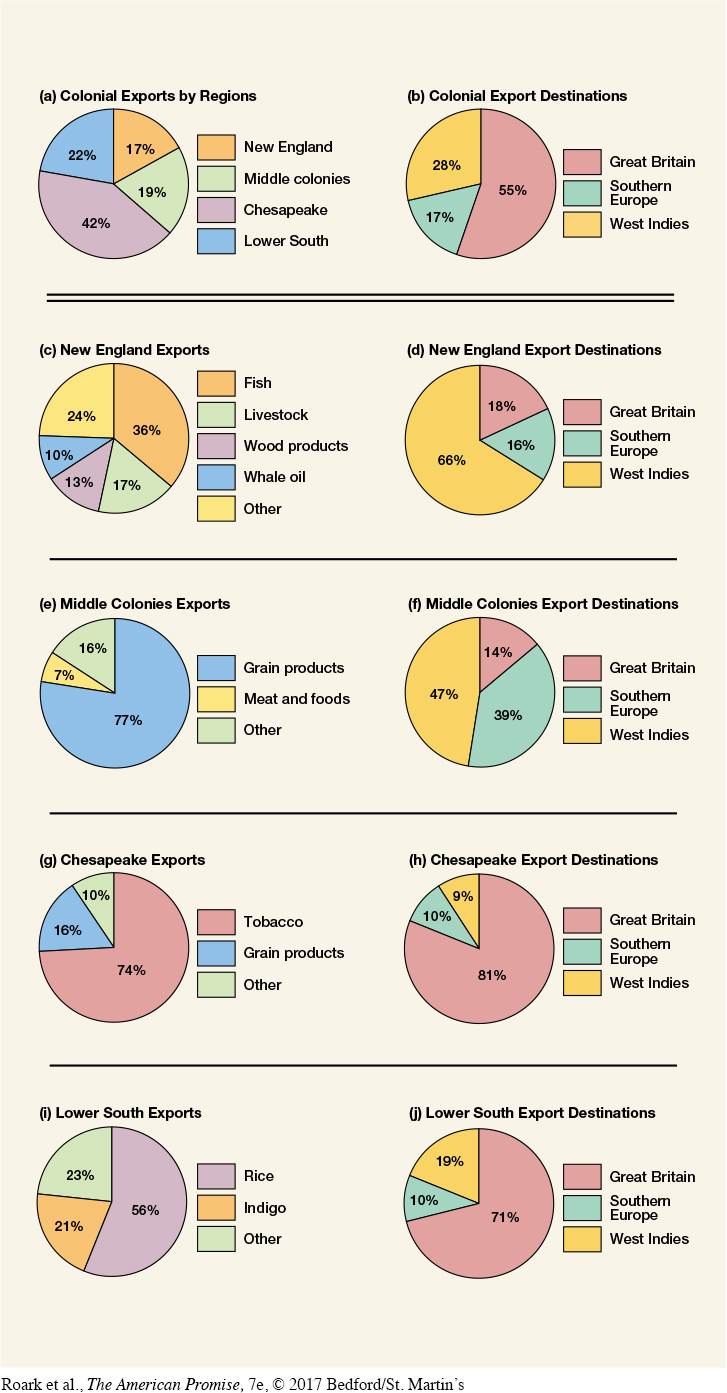

Commerce and Consumption

Eighteenth-

The American Promise: Printed Page 123

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 115

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 133

Page 124

The American Promise: Printed Page 123

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 115

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 133

Page 125The Atlantic commerce that took colonial goods to markets in Britain brought objects of consumer desire back to the colonies. British merchants and manufacturers recognized that colonists made excellent customers, and the Navigation Acts gave British exporters privileged access to the colonial market. By midcentury, export-

When the colonists’ eagerness to consume exceeded their ability to pay, British exporters willingly extended credit, and colonial debts soared. Imported mirrors, silver plates, spices, bed and table linens, clocks, tea services, wigs, books, and more infiltrated parlors, kitchens, and bedrooms throughout the colonies. Despite the many differences among the colonists, the consumption of British exports built a certain material uniformity across region, religion, class, and status.

The dazzling variety of imported consumer goods also presented women and men with a novel array of choices. In many respects, the choices might appear trivial: whether to buy knives and forks, teacups, a mirror, or a clock. But such small choices confronted eighteenth-