The American Promise: Printed Page 125

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 117

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 137

Religion, Enlightenment, and Revival

Eighteenth-

The varieties of Protestant faith and practice ranged across a broad spectrum. The middle colonies and the southern backcountry included militant Baptists and Presbyterians. Huguenots who had fled persecution in Catholic France peopled congregations in several cities. In New England, old-

The American Promise: Printed Page 125

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 117

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 137

Page 126Many educated colonists became deists, looking for God’s plan in nature more than in the Bible. Deism shared the ideas of eighteenth-

Most eighteenth-

The American Promise: Printed Page 125

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 117

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 137

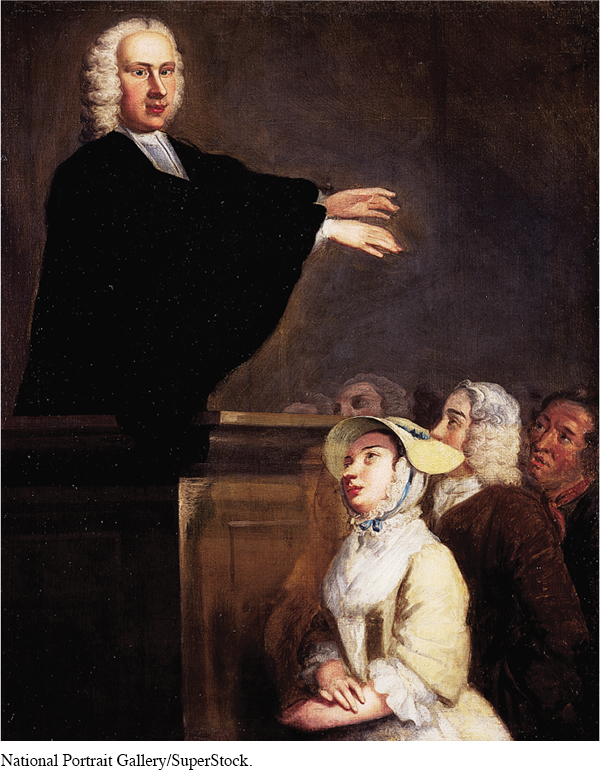

Page 127The spread of religious indifference, of deism, of denominational rivalry, and of comfortable backsliding profoundly concerned many Christians. A few despaired that, as one wrote, “religion . . . lay a-

Whitefield’s successful revivals spawned many lesser imitations. Itinerant preachers, many of them poorly educated, roamed the colonial backcountry after midcentury. Bathsheba Kingsley, a member of Jonathan Edwards’s flock, preached the revival message informally—

The revivals awakened and refreshed the spiritual energies of thousands of colonists struggling with the uncertainties and anxieties of eighteenth-