The American Promise: Printed Page 181

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 167

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 191

Prisoners of War

The American Promise: Printed Page 181

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 167

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 191

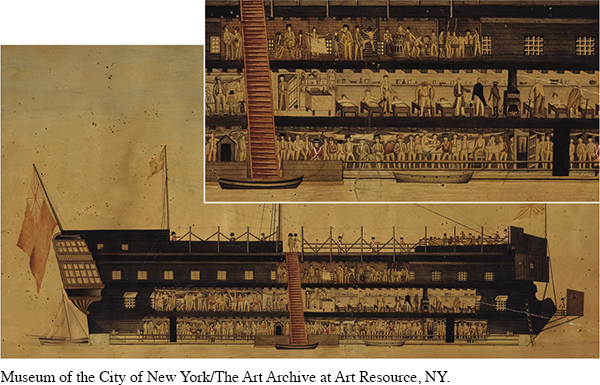

Page 181The poor handling of loyalists as traitors paled in comparison to the handling of American prisoners of war by the British. Among European military powers, humane treatment of captured soldiers was the custom, including adequate provisions (paid for by the captives’ own government) and the possibility of prisoner exchanges. But British leaders refused to see American captives as foot soldiers employed by a sovereign nation. Instead they were traitors, to be treated worse than common criminals.

The 4,000 American prisoners taken in the fall of 1776 were crowded onto two dozen vessels anchored in the river between Manhattan and Brooklyn. The largest ship, the HMS Jersey, was a broken-

Treating the captives as criminals potentially triggered the Anglo-

Despite the prison-

Such exchanges were negotiated when the British became desperate to regain valued officers and thus freed American officers. Death was the most common fate of ordinary American soldiers and seamen. More than 15,000 men endured captivity in the prison ships, and two-

The American Promise: Printed Page 181

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 167

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 191

Page 182