The American Promise: Printed Page 192

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 202

BEYOND AMERICA’S BORDERS

The American Promise: Printed Page 192

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 202

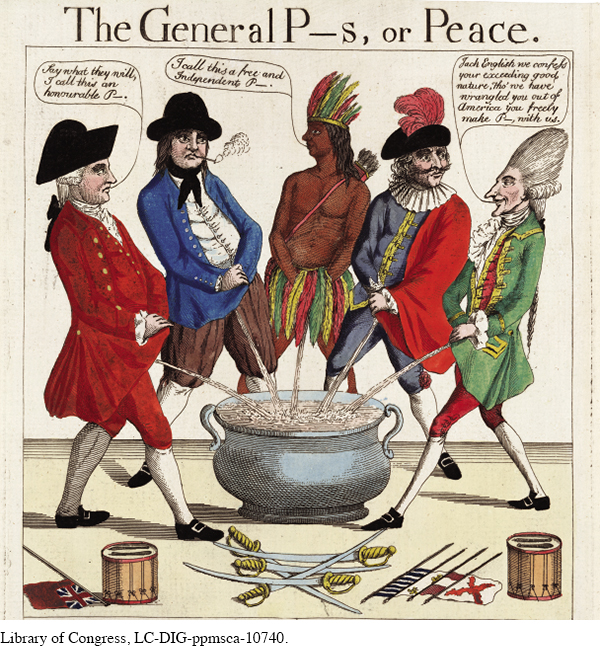

Page 192European Nations and the Peace of Paris, 1783

News of the decisive British defeat at Yorktown in late 1781 caused Britain’s prime minister, Lord North, to stagger as though wounded and exclaim, “Oh, God, it is all over!” But in truth, it was far from over. A full year elapsed before the elements of a formal peace treaty could be worked out, and an additional year passed before the treaty was signed and Britain finally ended its occupation of New York City. The delay occurred in part because several European countries besides Britain had stakes in the war that had nothing to do with the chief American goal of political independence.

France had entered the war mainly to thwart and damage Britain. Certainly the French monarchy had no real sympathy for a democratic revolution in the British colonies. Indeed, for months before the victory at Yorktown, French leaders conferred covertly with the British about a plan to divide the colonies among the key European powers, with Britain to retain New York City and the rice and tobacco colonies of the South, while France and Spain would carve up the rest.

The stubbornness of Britain’s George III prevented such a deal. Even after receiving news of the defeat at Yorktown, the delusional king still imagined he could retain all thirteen rebellious colonies. After a series of antiwar votes in Parliament and the resignation of Lord North, George III briefly considered abdicating his throne. Instead, he replaced North with a new minister, Lord Shelburne, who approached the peace talks with the view that independence for America was still up for debate.

Spain’s interest in the war stemmed from a secret alliance with France in 1779. The Spanish king wanted to oust the British from Gibraltar, a tiny three-

At various times, Russia, Austria, and Poland had agents in Paris offering to mediate peace talks in order to adjust the balance of power in Europe. None of these countries viewed American independence as a priority. Only Holland offered formal diplomatic recognition of the new country, an act of faith quickly followed up by a sizable loan of money to the new government. No other country was so supportive.

The Continental Congress entrusted three Americans of great distinction to handle the treaty negotiations. Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay considered independence as the precondition for the talks to begin, so they were taken aback when the British negotiator showed up with credentials that pointedly addressed them as “the Commissioners of the Colonies.” A month later, updated credentials referenced the three as representatives “of the Thirteen United States of America,” a far more satisfactory acknowledgment of their new standing. In September 1782, peace talks began in earnest. Shelburne conceded on independence and set his goal as the maintenance of favored trading status with the new country. He saw, perhaps more clearly than did his king, that although Britain’s political dominance over its colonies had now ended, economic dominance might nicely replace it.

The congress also instructed its three diplomats to consult France at every step of the negotiation with Britain, a condition insisted on by the French minister to the United States. But Jay and Adams had deep suspicions of the motives of the French foreign minister, the Count of Vergennes. They feared, with good reason, that Vergennes planned on placing their nation’s western boundary some distance east of the Mississippi River, to meet the demands of Spain. So the Americans sidestepped their instructions and negotiated with Britain in secret, producing an acceptable draft treaty in just a few weeks.

By January 1783, France, Britain, and Spain had produced their own treaties, involving deals with lands in India, Africa, and the Mediterranean, and in September of that year all the treaties were officially approved and signed. Franklin wrote to a friend in Massachusetts, “We are now Friends with England and with all Mankind. May we never see another War! for in my Opinion, there never was a good War, or a bad Peace.”

Questions for Analysis

Summarize the Argument: What was at stake for France and Spain in the American Revolution? How were those goals reflected in their bargaining positions at the treaty meetings?

Recognize Viewpoints: Compare the views and hopes of King George at the conclusion of the war with those of his ministers, Lord North and Lord Shelburne.

Consider the Context: Many Indian tribes fought boldly with their British allies in the Revolution, so why did they not participate in the treaty making in Paris? Did Britain represent any of the tribes’ interests in the diplomatic agreements?