The American Promise: Printed Page 172

MAKING HISTORICAL ARGUMENTS

The American Promise: Printed Page 172

Page 172How Did “New Media” Push Forward the Declaration of Independence?

In a world without public opinion polls, how did the Continental Congress know it had the support of the people? A close study of the way news and opinion circulated in the mid-

Printers had a hand in all aspects of the communication grid, and they therefore became significant players in educating Americans about the contested issues in the conflict with Britain. One such ardent printer was Isaiah Thomas, editor of the Massachusetts Spy in Boston between 1770 and 1775. Just twenty-

Newspapers like the Spy formed the backbone of a networked system of communication that emerged in the Revolutionary period. In 1775, some forty newspapers were published in coastal cities. In peaceful times, they were sedate four-

The Boston papers traveled to distant cities by horse free of charge, thanks to a royal postal system that favored newspaper exchanges. While private letters with paid postage were given preferential treatment, the free newspapers went into a secondary satchel, which could be selectively thinned by a postmaster whenever the paid mail got heavy. In 1774, British authorities realized that postmasters had the power to control the flow of information. What if Isaiah Thomas’s version of events could not make it to Virginia? British authorities fired the American in charge of the royal postal system, intending to replace him and others with men loyal to Britain who could dispose of seditious newspapers. In response, the Second Continental Congress quickly created its own postal system. Printers lined up to be postmasters, eager to be stationed at the local entry point for incoming news.

Protecting the new postal system was vital. Privacy was essential when writing candidly about treasonous matters, and private letters between political men contained crucial exchanges of information. Equally vital were public letters to the editor written by individual Americans. Although the concept of investigative reporting lay far in the future, letters from well-

Printers also produced political broadsides—

The American Promise: Printed Page 172

Page 173In early 1776, similar techniques created a groundswell of popular support for a Declaration of Independence. Spurred by their state assembly, ninety Massachusetts towns held town meetings to debate and vote on independence. Their thoughtful and distinctive justifications, all affirmative, were forwarded to the Continental Congress. Towns in Maryland and Virginia also met to instruct their delegates to vote for independence, as did four of the new state assemblies. The weight of these actions helped push the Declaration to reality.

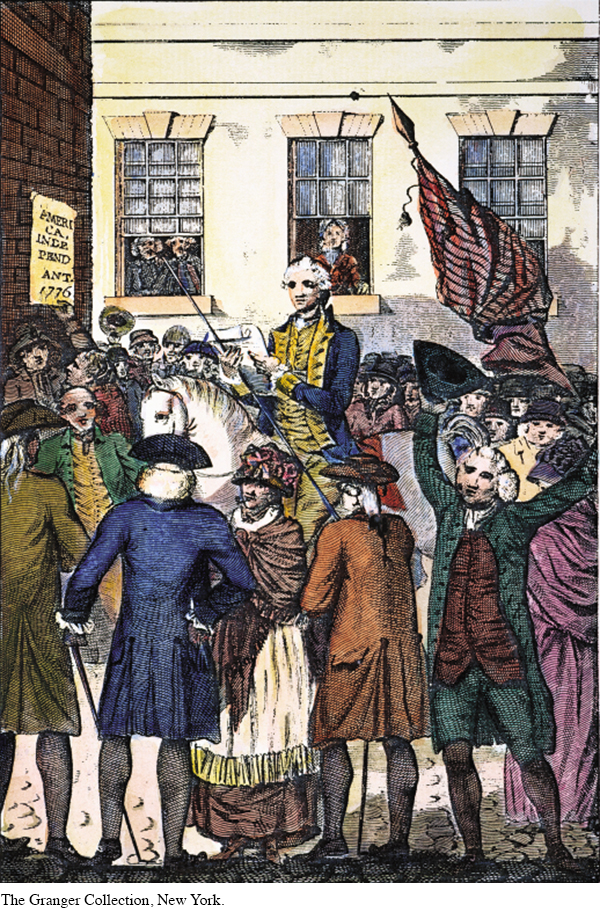

Swift post riders carried specially printed copies of the Declaration to each state. As the copy destined for Boston passed through Worcester, Isaiah Thomas got his hands on it and read it to a cheering crowd, who pulled symbols of the monarchy off the courthouse and raised beer mugs to patriotic toasts. The next morning, Thomas learned that his apprentice had run off to join the Continental army, leaving him short-

Questions for Analysis

Summarize the Argument: What new or changed modes of communication emerged in the 1770s? How did these new capabilities expand the reach and impact of revolutionary ideas and enthusiasm?

Analyze the Evidence: Which of the several elements of networked communications—

Consider the Context: In 1776, very few American newspaper editors were loyalists. Can you suggest some reasons why? What might this fact reveal about the political divisions that existed within the colonies in this period?