The American Promise: Printed Page 232

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 213

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 244

Agriculture, Transportation, and Banking

Dramatic increases in international grain prices, caused by underproduction in war-

Cotton production also boomed, spurred by market demand from British textile manufacturers and a mechanical invention. Limited amounts of smooth-

A surge of road building further stimulated the economy. Before 1790, one road connected Maine to Georgia, but with the establishment of the U.S. Post Office in 1792, road mileage increased sixfold. Private companies also built toll roads, such as the Lancaster Turnpike west of Philadelphia, the Boston-

The American Promise: Printed Page 232

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 213

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 244

Page 233A third development signaling economic resurgence was the growth of commercial banking. During the 1790s, the number of banks nationwide multiplied tenfold, from three to twenty-

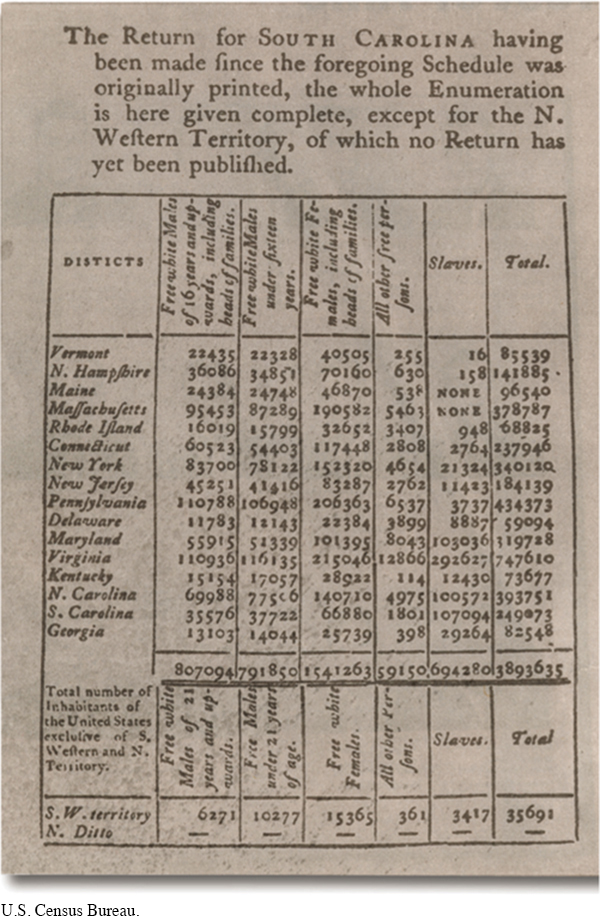

The U.S. population expanded along with economic development, propelled by large average family size and better than adequate food and land resources. As measured by the first two federal censuses in 1790 and 1800, the population grew from 3.9 million to 5.3 million, an increase of 35 percent.