The American Promise: Printed Page 247

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 228

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 260

The Alien and Sedition Acts

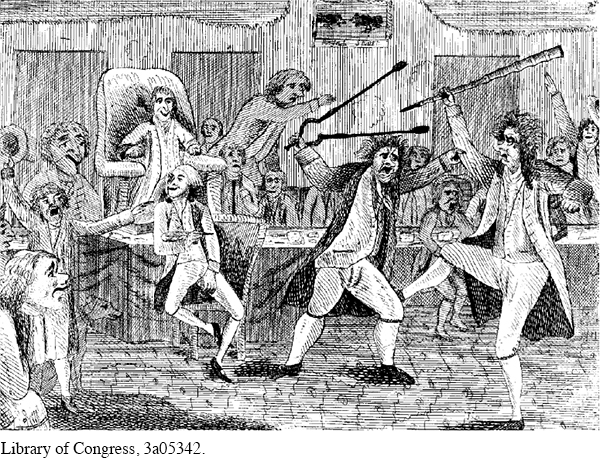

With tempers so dangerously high and fears that political dissent was akin to treason, Federalist leaders moved to muffle the opposition. In mid-

Congress also passed two Alien Acts. The first extended the waiting period for an alien to achieve citizenship from five to fourteen years and required all aliens to register with the federal government. The second empowered the president in time of war to deport or imprison without trial any foreigner suspected of being a danger to the United States. The clear intent of these laws was to harass French immigrants already in the United States and to discourage others from coming.

Republicans strongly opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts on the grounds that the acts conflicted with the Bill of Rights, but they did not have the votes to revoke the acts in Congress, nor could the federal judiciary, dominated by Federalist judges, be counted on to challenge them. Jefferson and Madison turned to the state legislatures, the only other competing political arena, to press their opposition. Each man anonymously drafted a set of resolutions condemning the acts and convinced the legislatures of Virginia and Kentucky to present them to the federal government in late fall 1798. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions tested the novel argument that state legislatures have the right to judge and even nullify the constitutionality of federal laws, bold claims that held risk that one or both men could be accused of sedition. The resolutions in fact made little dent in the Alien and Sedition Acts, but the idea of a state’s right to nullify federal law did not disappear. It would resurface several times in decades to come, most notably in a major tariff dispute in 1832 and in the sectional arguments that led to the Civil War.

Amid all the war hysteria and sedition fears in 1798, President Adams regained his balance. He was uncharacteristically restrained in pursuing opponents under the Sedition Act, and he finally refused to declare war on France, as extreme Federalists wished. No doubt he was beginning to realize how much he had been the dupe of Hamilton. He also shrewdly realized that France was not eager for war and that a peaceful settlement might be close at hand. In January 1799, a peace initiative from France arrived in the form of a letter assuring Adams that diplomatic channels were open again and that new peace commissioners would be welcomed in France. Adams accepted this overture and appointed new negotiators. By late 1799, the Quasi-

Still, he won candidacy for the 1800 election, handpicked by a small set of Adams loyalists. Adams’s Republican opponent was Thomas Jefferson. Faced with this choice, Hamilton supported Jefferson, but without enthusiasm: “If we must have an enemy at the head of government, let it be one whom we can oppose, and for whom we are not responsible.”

The American Promise: Printed Page 247

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 228

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 260

Page 249When the election was finally over, President Jefferson mounted the inaugural platform to announce, “We are all republicans, we are all federalists,” an appealing rhetoric of harmony appropriate to an inaugural address. But his formulation perpetuated a denial of the validity of party politics, a denial that ran deep in the founding generation of political leaders.

REVIEW How did war between Britain and France intensify the political divisions in the United States?