The Expanding Republic, 1815–1840

Printed Page 272 Chapter Chronology

The Expanding Republic, 1815-1840

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

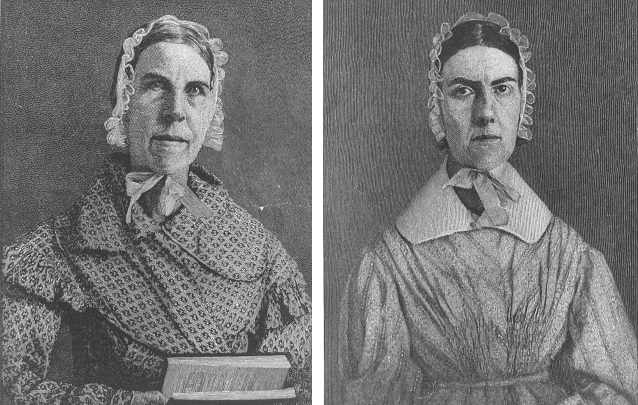

In 1837, audiences throughout Massachusetts witnessed the astonishing spectacle of two sisters from a wealthy southern family delivering impassioned speeches about the evils of slavery. Women lecturers were rare in the 1830s, but Sarah and Angelina Grimké were on a mission, channeling a higher power to authorize their outspokenness. Angelina explained that "whilst in the act of speaking I am favored to forget little ‘I' entirely & to feel altogether hid behind the great cause I am pleading." In their seventy-nine speaking engagements, forty thousand women — and men — came to hear them.

Not much in their family background predicted the sisters' radical break with tradition. They grew up in Charleston, where their father was chief justice of the State Supreme Court, yet somehow they managed to develop independent minds and a hatred of slavery. In the 1820s, both sisters moved to Philadelphia and joined the Quakers' Society of Friends.

The abolitionist movement was in its infancy in the 1830s, centered around Boston's William Lloyd Garrison, editor of the Liberator, who demanded an immediate end to slavery. In 1835, Angelina Grimké wrote to Garrison, describing herself as a white southern exile from slavery, and Garrison published her letter. Her rare voice of personal testimony caused a stir and propelled her into her new public career.

The sisters' 1837 extended tour of Massachusetts led to a doubling of membership in northern antislavery societies. Newspapers and religious leaders fiercely debated the Grimkés' boldness in presuming to lecture men, and the sisters defended their stand: "Whatever is morally right for a man to do is morally right for a woman to do," Angelina wrote. "I recognize no rights but human rights." Sarah produced a set of essays titled Letters on the Equality of the Sexes (1838), the first American treatise asserting women's equality with men.

The Grimké sisters' innovative radicalism was part of a vibrant, contested public life that came alive in the United States of the 1830s. This decade — often summed up as the Age of Jackson, in honor of the larger-than-life president — was a time of rapid economic, political, and social change. Andrew Jackson's bold self-confidence mirrored the new confidence of American society in the years after 1815. An entrepreneurial spirit gripped the country, producing a market revolution of unprecedented scale. Old social hierarchies eroded; ordinary men dreamed of moving high up the ladder of success. Stunning advances in transportation and economic productivity fueled such dreams and propelled thousands to travel west or to cities. Urban growth and technological change fostered the diffusion of a distinctive and lively public culture, spread mainly through the increased circulation of newspapers and also by thousands of public lecturers, like the Grimké sisters, allowing popular opinions to coalesce and intensify.

Expanded communication transformed politics dramatically. Sharp disagreements over the best way to promote individual liberty, economic opportunity, and national prosperity in the new economy defined key differences between presidential parties emerging in the early 1830s, attracting large numbers of white male voters into their ranks. Religion became democratized as well. A nationwide evangelical revival brought its adherents the certainty that salvation was now available to all.

Yet there were downsides. Steamboats blew up, banks and businesses periodically collapsed, alcoholism rates soared, Indians were killed or relocated farther west, and slavery continued to expand. The brash confidence that turned some people into rugged, self-promoting individuals inspired others to think about the human costs of rapid economic expansion and thus about reforming society in dramatic ways. The common denominator was a faith that people and societies could shape their own destinies.