The New West and the Free North, 1840–1860

Printed Page 302 Chapter Chronology

The New West and the Free North, 1840-1860

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

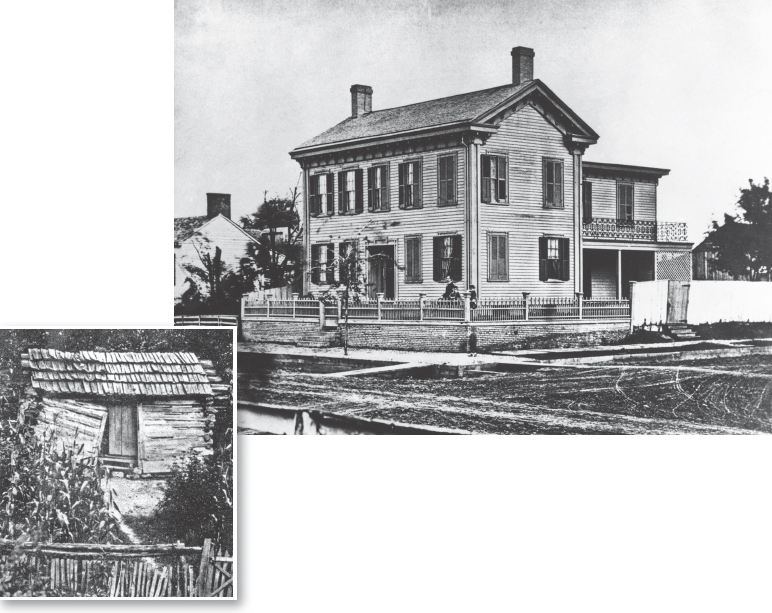

Early in November 1842, Abraham Lincoln and his new wife, Mary, moved into their first home in Springfield, Illinois, a small rented room on the second floor of the Globe Tavern, the nicest place that Abraham had ever lived in and the worst place that Mary had ever inhabited. She grew up in Lexington, Kentucky, attended by slaves in the elegant home of her father, a prosperous merchant and banker. In March 1861, the Lincolns moved into the presidential mansion in Washington, D.C.

Abraham Lincoln climbed from the Globe Tavern to the White House by work, ambition, and immense talent — traits he had honed since boyhood. Lincoln and many others celebrated his rise from humble origins as an example of the opportunities in the free-labor economy of the North and West. They attributed his spectacular ascent to his individual qualities and tended to ignore the help he received from Mary and many others.

Born in a Kentucky log cabin in 1809, Lincoln grew up on small, struggling farms as his family migrated west. His father, Thomas Lincoln, who had been born in Virginia, never learned to read and, as his son recalled, "never did more in the way of writing than to bunglingly sign his own name." Lincoln's mother, Nancy, could neither read nor write. In 1816, Thomas Lincoln moved his young family from Kentucky to the Indiana wilderness, where Abraham learned the arts of agriculture, but "there was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education," Lincoln recollected. By contrast, Mary Todd received ten years of schooling in Lexington's best private academies for young women.

In 1830, Thomas Lincoln decided to move farther west and headed to central Illinois. The next spring, when Thomas moved yet again, Abraham set out on his own, a "friendless, uneducated, penniless boy," as he described himself.

By dogged striving, Abraham Lincoln gained an education and the respect of his Illinois neighbors, although a steady income eluded him for years. The newlyweds received help from Mary's father, including eighty acres of land and a yearly allowance of about $1,100 for six years that helped them move out of their room above the Globe Tavern and into their own home. Abraham eventually built a thriving law practice in Springfield, Illinois, and served in the state legislature and in Congress. Mary helped him in many ways, rearing their sons, tending their household, and integrating him into her wealthy and influential extended family in Illinois and Kentucky. Mary also shared Abraham's keen interest in politics and ambition for power. With Mary's support, Abraham became the first president born west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Like Lincoln, millions of Americans believed they could make something of themselves, whatever their origins, so long as they were willing to work. Individuals who were lazy, undisciplined, or foolish had only themselves to blame if they failed, advocates of free-labor ideology declared. Work was a prerequisite for success, not a guarantee. This emphasis on work highlighted the individual efforts of men and tended to slight the many crucial contributions of women and family members to the successes of men like Lincoln.

In addition, the rewards of work were skewed toward white men and away from women and free African Americans, as antislavery and woman's rights reformers pointed out. Nonetheless, the promise of such rewards spurred efforts that shaped the contours of America, plowing new fields and building railroads that pushed the boundaries of the nation ever westward to the Pacific Ocean. The nation's economic, political, and geographic expansion raised anew the question of whether slavery should also move west, the question that Lincoln and other Americans confronted repeatedly following the Mexican-American War, yet another outgrowth of the nation's ceaseless westward movement.