The Slave South, 1820-1860

Printed Page 332 Chapter Chronology

The Slave South, 1820-1860

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

Nat Turner was born a slave in Southampton County, Virginia, in October 1800. His parents noticed special marks on his body, which they said were signs that he was "intended for some great purpose." As an adolescent, he adopted an austere lifestyle of Christian devotion and fasting. In his twenties, he received visits from the "Spirit," the same spirit, he believed, that had spoken to the ancient prophets. In time, Nat Turner began to interpret these things to mean that God had appointed him an instrument of divine vengeance for the sin of slaveholding.

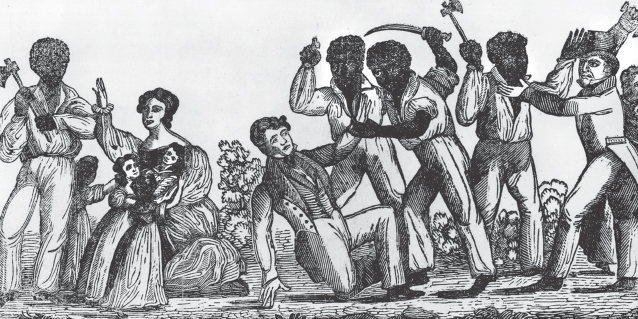

On the morning of August 22, 1831, he set out with six friends — Hark, Henry, Sam, Nelson, Will, and Jack — to punish slave owners. Turner struck the first blow, an ax to the head of his master, Joseph Travis. The rebels killed all of the white men, women, and children they encountered. By noon, they had visited eleven farms and slaughtered fifty-seven whites. Along the way, they had added fifty or sixty men to their army. Word spread quickly, and soon the militia and hundreds of local whites gathered. They quickly captured or killed all of the rebels except Turner, who hid out for about ten weeks before being captured in nearby woods. Within a week, he was tried, convicted, and executed. By then, forty-five slaves had stood trial, twenty had been convicted and hanged, and another ten had been banished from Virginia. Frenzied whites had killed another hundred or more blacks — insurgents and innocent bystanders — in their counterattack against the rebellion.

White Virginians blamed the rebellion on outside agitators. In 1829, David Walker, a freeborn black man living in Boston, had published his Appeal ...to the Coloured Citizens of the World, an invitation to slaves to rise up in bloody revolution, and copies had fallen into the hands of Virginia slaves. Moreover, on January 1, 1831, the Massachusetts abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison had published the first issue of the Liberator, his fiery newspaper (see chapter 11).

In the months following the insurrection, the Virginia legislature reaffirmed the state's determination to preserve slavery by passing laws that strengthened the institution and further restricted free blacks. A professor at the College of William and Mary, Thomas R. Dew, published a vigorous defense of slavery that became the bible of Southerners' proslavery arguments. More than ever, the nation was divided along the Mason-Dixon line, the surveyors' mark that in colonial times had established the boundary between Maryland and Pennsylvania but half a century later divided the free North and the slave South.

Black slavery increasingly molded the South into a distinctive region. In the decades after 1820, Southerners, like Northerners, raced westward, but unlike Northerners who spread small farms, manufacturing, and free labor, Southerners spread slavery, cotton, and plantations. Geographic expansion meant that slavery became more vigorous and more profitable than ever, embraced more people, and increased the South's political power. Antebellum Southerners sometimes found themselves at odds with one another — not only slaves and free people but also women and men; Indians, Africans, and Europeans; and aristocrats and common folk. Nevertheless, beneath this diversity, a distinctively southern society and culture were forming. The South became a slave society, and most white Southerners were proud of it.