The City and Its Workers, 1870–1900

Printed Page 504 Chapter Chronology

The City and Its Workers, 1870-1900

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

"Atown that crawled now stands erect, and we whose backs were bent above the hearths know how it got its spine," boasted a steelworker surveying New York City. Where once wooden buildings stood rooted in the mire of unpaved streets, cities of stone and steel sprang up in the last decades of the nineteenth century. The labor of millions of workers, many of them immigrants, laid the foundations for urban America.

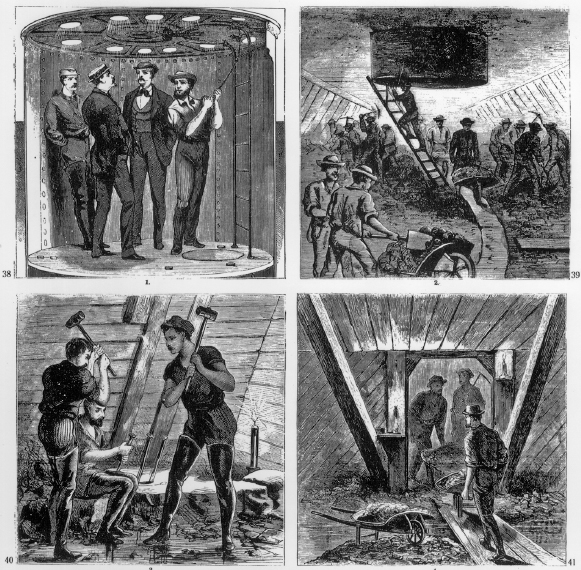

No symbol better represented the new urban landscape than the Brooklyn Bridge, opened in May 1883. The great bridge soared over the East River in a single mile-long span. Building the Brooklyn Bridge took fourteen years and cost the lives of twenty-seven men. To sink the foundation in the riverbed, laborers tunneled through the mud and worked in boxes that were open at the bottom and pressurized to keep the water out. Before long, workers experienced the malady they called "bends" because it left them doubled over in pain when they rose to the surface (something that scientists later learned resulted from nitrogen bubbles trapped in the bloodstream and could be prevented by allowing for decompression). The first death occurred when the foundation reached a depth of seventy-one feet. A German immigrant complained that he did not feel well. He collapsed and died on his way home. Eight days later, another man dropped dead, and the entire workforce went out on strike. Terrified workers demanded a higher wage for fewer hours of work.

A scrawny sixteen-year-old from Ireland, Frank Harris remembered the fearful experience of going to work on the bridge a few days after landing in America:

The six of us were working naked to the waist in the small iron chamber with the temperature of about 80 degrees Fahrenheit: In five minutes the sweat was pouring from us, and all the while we were standing in icy water that was only kept from rising by the terrific pressure. No wonder the headaches were blinding.

By his fifth day, Harris quit. Many immigrant workers walked off the job, often as many as a hundred a week. But a ready supply of immigrants meant that new workers took up the digging, where they could earn in a day more than they made in a week in Ireland or Italy.

Begun in 1869, the bridge was the dream of builder John Roebling, who died in a freak accident almost as soon as construction began. Washington Roebling took over as chief engineer after his father's death and routinely worked twelve to fourteen hours six days a week. Soon he, too, fell victim to the "bends" and, bedridden, directed the completion of the bridge through a telescope from his window in Brooklyn Heights. His wife, Emily Warren Roebling, acted as site superintendent and general engineer of the project.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the Brooklyn Bridge stood as a symbol of many things: the industrial might of the United States; the labor of the nation's immigrants; the ingenuity and genius of its engineers and inventors; the rise of iron and steel; and, most of all, the ascendancy of urban America. Poised on the brink of the twentieth century, the nation was shifting from a rural, agricultural society to an urban, industrial nation. The gap between rich and poor widened. In the burgeoning cities, tensions erupted into conflict as workers squared off to fight to organize into labor unions and to demand safer working conditions, shorter hours, and better pay, sometimes with violent and bloody results. The explosive growth of the cities fostered political corruption as unscrupulous bosses and entrepreneurs cashed in on the building boom. Immigrants, political bosses, middle-class managers, poor laborers, and the very rich populated the nation's cities, crowding the streets, laboring in the stores and factories, and taking their leisure at the new ballparks, amusement parks, dance halls, and municipal parks. As the new century dawned, the city and its workers moved to center stage in American life.