Dissent, Depression, and War, 1890–1900

Printed Page 532 Chapter Chronology

Dissent, Depression, and War, 1890-1900

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

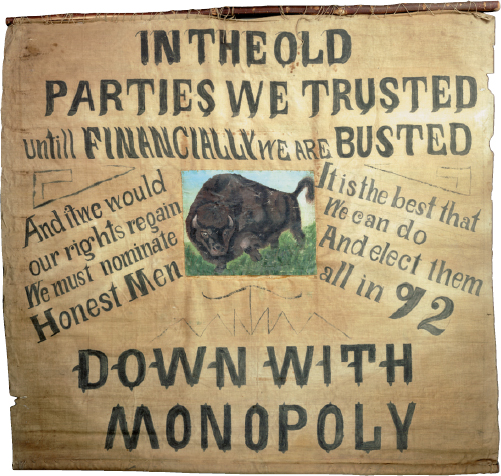

Frances Willard traveled to St. Louis in February 1892 with high hopes. Political change was in the air, and Willard was there to help fashion a new reform party. As head of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), an organization with members in every state and territory in the nation, Willard wielded considerable clout. At her invitation, twenty-eight of the country's leading reformers met in Chicago to draft a set of principles to bring to St. Louis. No American woman before her had played such a central role in a political movement. At the height of her power, Willard took her place among the leaders onstage in St. Louis.

Exposition Music Hall presented a colorful spectacle. "The banners of the different states rose above the delegates throughout the hall, fluttering like the flags over an army encamped," wrote one reporter. The fiery orator Ignatius Donnelly attacked the money kings of Wall Street. Terence V. Powderly, head of the Knights of Labor, called on workers to join hands with farmers against the "nonproducing classes." And Frances Willard took the podium, urging the crowd to outlaw liquor and give women the vote.

Delegates hammered out a series of demands, breathtaking in their scope. They tackled the tough questions of the day — the regulation of business, the need for banking and currency reform, the right of labor to organize and bargain collectively, and the role of the federal government in regulating business, curbing monopoly, and giving the people greater voice. But the new party determined to stick to economic issues and resisted endorsing either temperance or woman suffrage. As a member of the platform committee, Willard fought for both and complained of the "crooked methods ...employed to scuttle these planks."

The convention ended its work amid a chorus of cheers. According to one eyewitness, "Hats, paper, handkerchiefs, etc., were thrown into the air; ...cheer after cheer thundered and reverberated through the vast hall reaching the outside of the building where thousands who had been waiting the outcome joined in the applause till for blocks in every direction the exultation made the din indescribable."

What was all the shouting about? The crowd, fed up with the Democrats and the Republicans, celebrated the birth of a new political party, officially named the People's Party. The St. Louis gathering marked an early milestone in one of the most turbulent decades in U.S. history. An agrarian revolt, labor strikes, a severe depression, and a war shook the 1890s. As the decade opened, Americans flocked to organizations including the Farmers' Alliance, the American Federation of Labor, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, and the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Their political alliance gave birth to the People's (or Populist) Party. In a decade of unrest and uncertainty, the Populists countered laissez-faire economics by insisting that the federal government play a more active role to ensure economic fairness in industrial America.

This challenge to the status quo culminated in 1896 in one of the most hotly contested presidential elections in the nation's history. At the close of the tumultuous decade, the Spanish-American War brought the country together, with Americans rallying to support the troops. American imperialism and overseas expansion raised questions about the nation's role on the world stage as the United States stood poised to enter the twentieth century.