Progressivism from the Grass Roots to the White House, 1890–1916

Printed Page 560 Chapter Chronology

Progressivism from the Grass Roots to the White House, 1890-1916

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

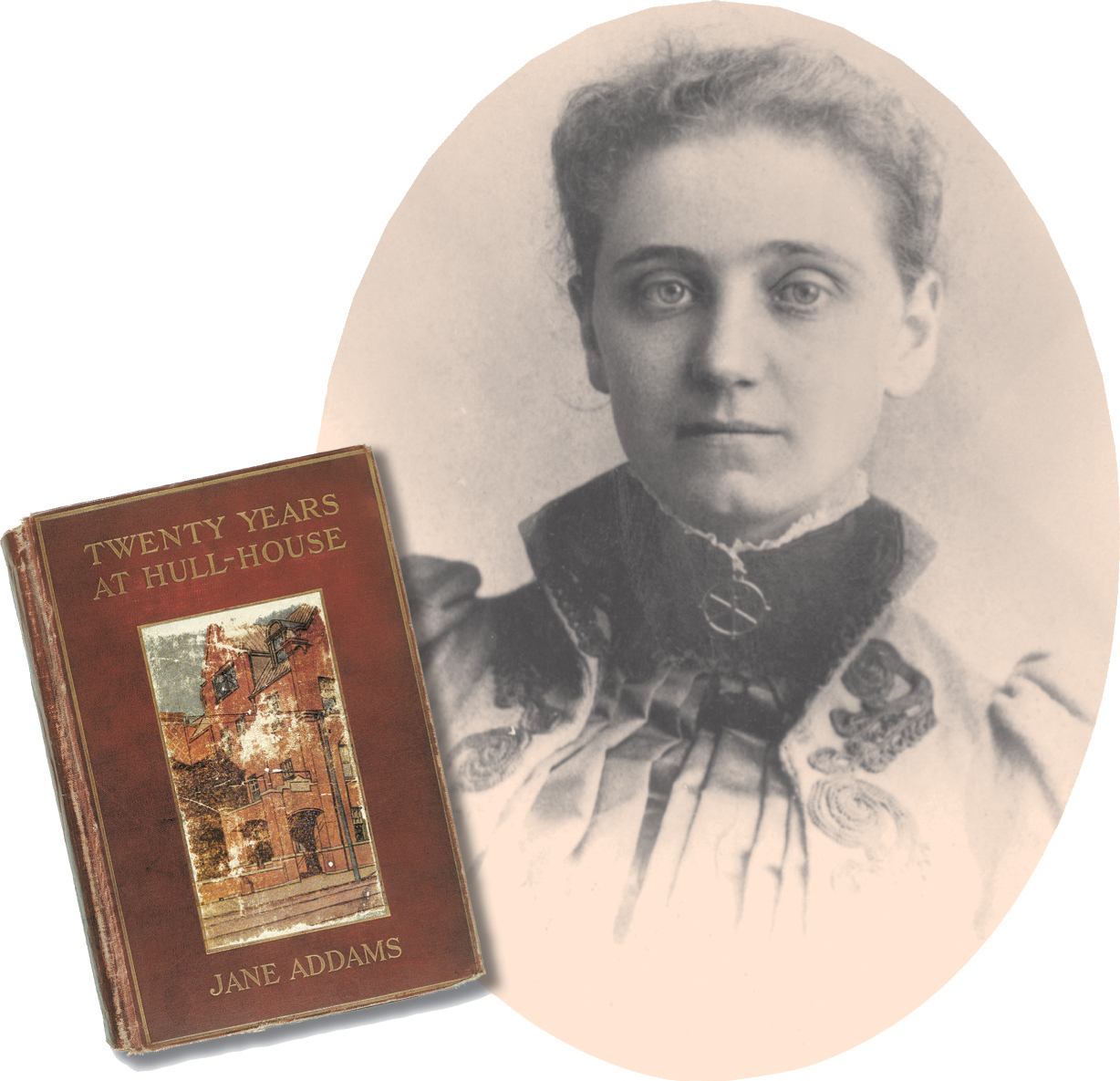

In the summer of 1889, Jane Addams leased two floors of a dilapidated mansion on Chicago's West Side. Her immigrant neighbors must have wondered why this well-dressed woman, who surely could afford better housing, chose to live on South Halsted Street. Yet the house, built by Charles Hull, precisely suited Addams's needs.

For Addams, personal action marked the first step in her search for solutions to the social problems created by urban industrialism. She wanted to help her immigrant neighbors, and she wanted to offer meaningful work to educated women like herself. Addams's emphasis on the reciprocal relationship between the social classes made Hull House different from other philanthropic enterprises. She wished to do things with, not just for, Chicago's poor.

In the next decade, Hull House expanded from two rented floors in the old brick mansion to some thirteen buildings housing a remarkable variety of activities. Addams provided public baths, opened a restaurant for working women too tired to cook after their long shifts, and sponsored a nursery and kindergarten. Hull House offered classes, lectures, art exhibits, musical instruction, and college extension courses. It boasted a gymnasium, a theater, a manual training workshop, a labor museum, and the first public playground in Chicago.

From the first, Hull House attracted an extraordinary set of reformers who pioneered the scientific investigation of urban ills. Armed with statistics, they launched campaigns to improve housing, end child labor, fund playgrounds, and lobby for laws to protect workers.

Addams quickly learned that it was impossible to deal with urban problems without becoming involved in politics. Piles of decaying garbage overflowed Halsted Street's wooden trash bins, breeding flies and disease. To rectify the problem, Addams got herself appointed garbage inspector. Out on the streets at six in the morning, she rode atop the garbage wagon to make sure it made its rounds. Eventually, her struggle to aid the urban poor led her on to the state capitol and to Washington, D.C.

Under Jane Addams's leadership, Hull House became a "spearhead for reform," part of a broader movement that contemporaries called progressivism. The transition from personal action to political activism that Addams personified became one of the hallmarks of this reform period, which lasted from the 1890s through World War I.

Classical liberalism, which opposed the tyranny of centralized government, did not address the enormous power of Gilded Age business giants. As the gap between rich and poor widened in the 1890s, progressive reformers demonstrated a willingness to use the government to counterbalance the power of private interests and in doing so redefined liberalism in the twentieth century.

Faith in activism united an otherwise diverse group of progressive reformers. A sense of Christian mission inspired some. Others, fearing social upheaval, sought to remove some of the worst evils of urban industrialism — tenements, child labor, and harsh working conditions. A belief in technical expertise and scientific management infused progressivism and made the cult of efficiency part of the movement.

Progressives shared a growing concern about the power of wealthy individuals and a distrust of the trusts, but they were not immune to the prejudices of their era. Although they called for greater democracy, many progressives sought to restrict the rights of African Americans, Asians, and even the women who formed the backbone of the movement.

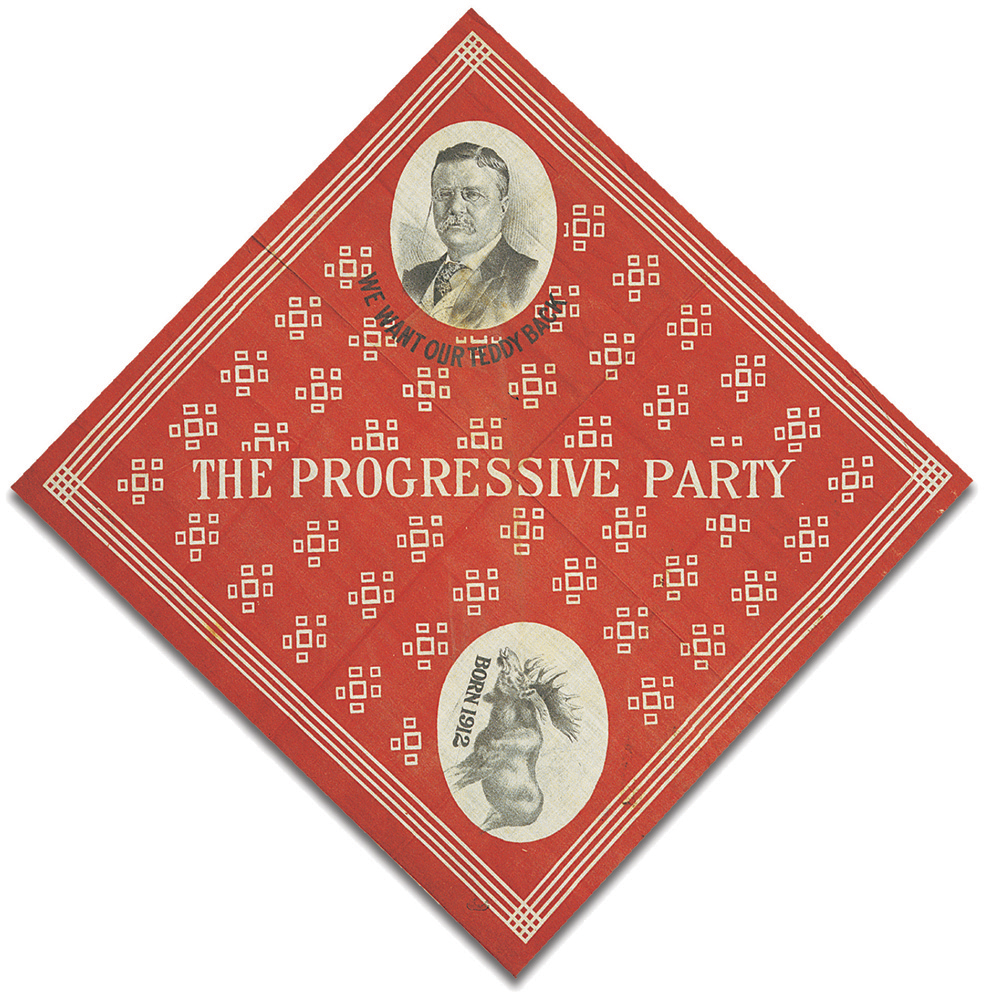

Uplift and efficiency, social justice and social control, direct democracy and discrimination all came together in the Progressive Era at every level of politics and in the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. While in office, Roosevelt advocated conservation, antitrust reforms, and championed the nation as a world power. Roosevelt's successor, William Taft, failed to follow in Roosevelt's footsteps, and the resulting split in the Republican Party paved the way for Wilson's victory in 1912. A reluctant progressive, Wilson eventually presided over reforms in banking, business, and labor.