World War I: The Progressive Crusade at Home and Abroad, 1914–1920

Printed Page 590 Chapter Chronology

World War I: The Progressive Crusade at Home and Abroad, 1914-1920

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

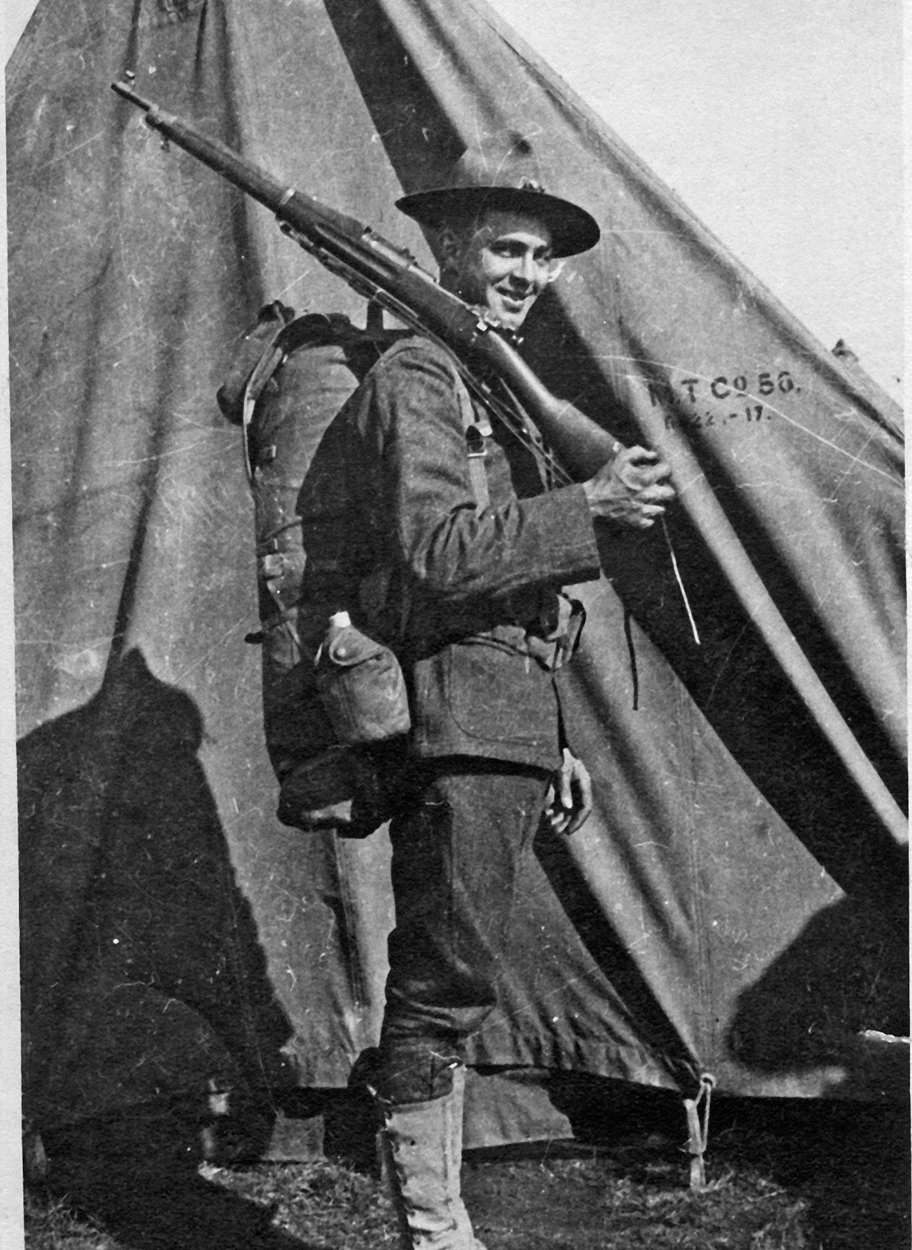

George "Brownie" Browne was one of 2 million soldiers who crossed the Atlantic during World War I to serve in the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France. The twenty-three-year-old civil engineer from Waterbury, Connecticut, volunteered in July 1917, three months after the United States entered the war, serving with the 117th Engineers Regiment, 42nd Division. Two-thirds of the "doughboys" (American soldiers in Europe) saw action during the war, and few white troops saw more than Brownie did.

When the 42nd arrived at the front, veteran French troops taught Brownie's regiment of engineers how to build and maintain trenches, barbed-wire entanglements, and artillery and machine-gun positions. Although Brownie came under German fire each day, he wrote Martha Johnson, his girlfriend back home, "The longer I'm here the more spirit I have to ‘stick it out' for the good of humanity and the U.S. which is the same thing."

Training ended in the spring of 1918 when the Germans launched a massive offensive in the Champagne region. The German bombardment made the night "as light as daytime, and the ground ...was a mass of flames and whistling steel from the bursting shells." One doughboy from the 42nd remembered, "Dead bodies were all around me. Americans, French, Hun [Germans] in all phases and positions of death." Another declared that soon "the odor was something fierce. We had to put on our gas masks to keep from getting sick." Eight days of combat cost the 42nd nearly 6,500 dead, wounded, and missing, 20 percent of the division.

After only ten days' rest, Brownie and his unit joined in the first major American offensive, an attack against German defenses at Saint-Mihiel. On September 12, 3,000 American artillery launched more than a million rounds against German positions. This time the engineers preceded the advancing infantry, cutting through or blasting any barbed wire that remained. The battle cost the 42nd another 1,200 casualties, but Brownie was not among them.

At the end of September, the 42nd shifted to the Meuse-Argonne region, where it participated in the most brutal American fighting of the war. And it was there that Brownie's war ended. The Germans fired thousands of poison gas shells, and the gas, "so thick you could cut it with a knife," felled Brownie. When the war ended on November 11, 1918, he was recovering from his respiratory wounds at a camp behind the lines. Discharged from the army in February 1919, Brownie returned home, where he and Martha married. Like the rest of the country, they were eager to get on with their lives.

President Woodrow Wilson had never expected to lead the United States into the Great War, as the Europeans called it. When war erupted in 1914, he declared America's absolute neutrality. But trade and principle entangled the United States in Europe's troubles and gradually drew the nation into the conflict. Wilson claimed that America's participation would serve grand purposes and uplift both the United States and the entire world.

At home, the war helped progressives finally achieve their goals of national prohibition and woman suffrage, but it also promoted a vicious attack on Americans' civil liberties. Hyperpatriotism meant intolerance, repression, and vigilante violence. In 1919, Wilson sailed for Europe to secure a just peace. Unable to dictate terms to the victors, he accepted disappointing compromises. Upon his return to the United States, he met a crushing defeat that marked the end of Wilsonian internationalism abroad. Crackdowns on dissenters, immigrants, racial and ethnic minorities, and unions also signaled the end of the Progressive Era at home.