Mediterranean Trade and European Expansion.

Printed Page 28 Chapter Chronology

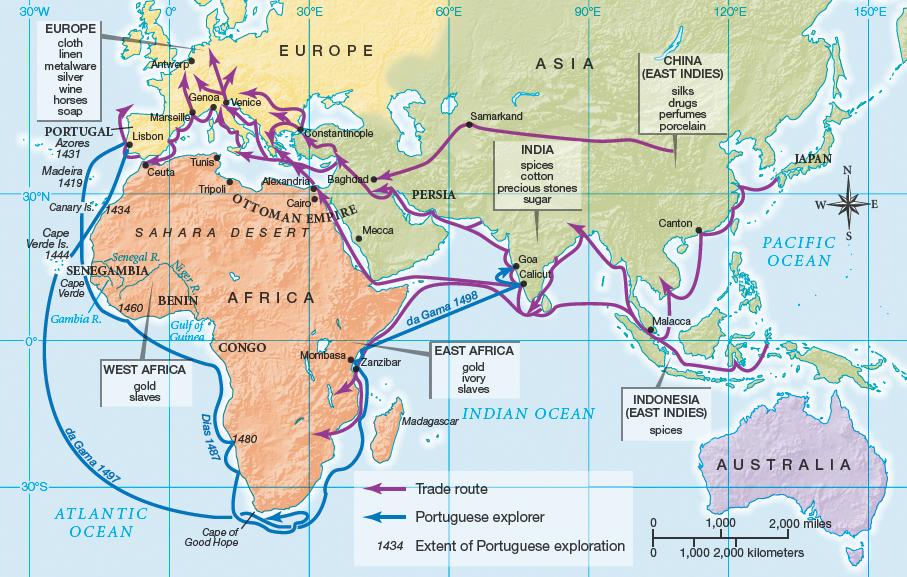

Mediterranean Trade and European Expansion. From the twelfth through the fifteenth centuries, spices, silk, carpets, ivory, and gold traveled overland from Persia, Asia Minor, India, and Africa and then funneled into continental Europe through Mediterranean trade routes (Map 2.1). Dominated primarily by the Italian cities of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa, this lucrative trade enriched Italian merchants and bankers. The vitality of the Mediterranean trade offered merchants few incentives to look for alternatives. New routes to the East and the discovery of new lands were the stuff of fantasy.

Black Death

A disease that in the mid-fourteenth century killed about a third of the European population and left a legacy of increased food and resources for the survivors as well as a sense of a world in precarious balance.

Preconditions for turning fantasy into reality developed in fifteenth-century Europe. In the mid-fourteenth century, a catastrophic epidemic of bubonic plague (or the Black Death, as it was called) killed about a third of the European population. This devastating pestilence had major long-term consequences. By drastically reducing the population, it made Europe’s limited supply of food more plentiful for survivors. Many survivors inherited property from plague victims, giving them new chances for advancement.

Understandably, most Europeans perceived the world as a place of alarming risks where the delicate balance of health, harvests, and peace could quickly be tipped toward disaster by epidemics, famine, and violence. Most people protected themselves from the constant threat of calamity by worshipping the supernatural, by living amid kinfolk and friends, and by maintaining good relations with the rich and powerful. But the insecurity and uncertainty of fifteenth-century European life also encouraged a few people to take greater risks, such as embarking on dangerous sea voyages through uncharted waters to points unknown.

In European societies, exploration promised fame and fortune to those who succeeded, whether they were kings or commoners. Monarchs such as Isabella hoped to enlarge their realms and enrich their dynasties by sponsoring journeys of exploration. More territory meant more subjects who could pay more taxes, provide more soldiers, and participate in more commerce, magnifying the monarch’s power and prestige. Voyages of exploration also could stabilize the monarch’s regime by diverting unruly noblemen toward distant lands. Some explorers, such as Columbus, were commoners who hoped to be elevated to the aristocracy as a reward for their daring achievements.

Scientific and technological advances also helped set the stage for exploration. The invention of movable type by Johannes Gutenberg around 1450 in Germany made printing easier and cheaper, stimulating the diffusion of information, including news of discoveries, among literate Europeans such as Isabella and Columbus. By 1400, crucial navigational aids employed by maritime explorers like Columbus were already available: compasses; hourglasses; and the astrolabe and quadrant, which were devices for determining latitude. The Portuguese were the first to use these technological advances in a campaign to sail beyond the limits of the world known to Europeans.