The Southern Colonies in the Seventeenth Century, 1601–1700

Printed Page 50 Chapter Chronology

The Southern Colonies in the Seventeenth Century, 1600-1700

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

In December 1607, after arriving at Jamestown with the first English colonists, Captain John Smith was captured by warriors of Powhatan, the supreme chief of about fourteen thousand Algonquian Indians who inhabited the coastal plain of present-day Virginia. According to Smith, Powhatan "feasted him after their best barbarous manner." Then, Smith recalled, "two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many [Indians] as could layd hands on [Smith], dragged him to [the stones], and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beate out his braines." At that moment, Pocahontas, Powhatan's eleven-year-old daughter, rushed forward and "got [Smith's] head in her armes, and laid her owne upon his to save him from death." Pocahontas, Smith wrote, "hazarded the beating out of her owne braines to save mine, and ...so prevailed with her father, that I was safely conducted [back] to James towne."

Historians believe that this episode happened more or less as Smith described it. But Smith did not understand why Pocahontas acted as she did. Most likely, what Smith interpreted as Pocahontas's saving him from certain death was instead a ritual enacting Powhatan's willingness to incorporate Smith and the white strangers at Jamestown into Powhatan's empire. By appearing to save Smith, Pocahontas was probably acting out Smith's new status as an adopted member of Powhatan's extended family.

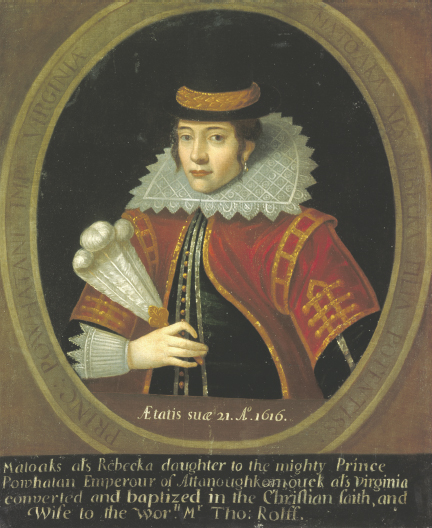

After Smith returned to England about two years later, relations between Powhatan and the English colonists deteriorated into bloody raids. In 1613, the colonists captured Pocahontas and held her hostage at Jamestown. Within a year, she converted to Christianity and married a colonist named John Rolfe. After giving birth to a son named Thomas, Pocahontas, her husband, and the new baby sailed for England in the spring of 1616. There, promoters of the Virginia colony dressed her as a proper Englishwoman and arranged for her to go to a ball attended by the king and queen.

Pocahontas died in England in 1617. Her son, Thomas, ultimately returned to Virginia, but the world he and his descendants inhabited was shaped by a reversal of the power ritualized when his mother "saved" John Smith. By the end of the seventeenth century, Native Americans no longer dominated the newcomers who arrived in the Chesapeake with John Smith.

During the seventeenth century, English colonists learned how to deviate from the example of New Spain (see chapter 2) by growing tobacco, a crop Native Americans had cultivated in small quantities for centuries. The new settlers grew enormous quantities of tobacco and exported most of it to England. Instead of incorporating Powhatan's people into their emerging society, the settlers encroached on Indian land and built new societies on the foundation of tobacco and transatlantic trade.

Producing large crop surpluses for export required hard labor and people who were willing — or could be forced — to do it. While New Spain took advantage of Native American labor, for the most part the Native Americans in British North America refused to be conscripted into the English colonists' fields. Instead, the settlers depended on the labor of family members, indentured servants, and, by the last third of the seventeenth century, African slaves.

By the end of the century, the southern colonies had become sharply different both from the world dominated by Powhatan when the Jamestown settlers first arrived and from seventeenth-century English society. In ways unimaginable to Powhatan, Pocahontas, and John Smith, the colonists paid homage to the international market and the English monarch by working mightily to make a good living growing crops for sale to the Old World.