The British Empire and the Colonial Crisis, 1754–1775

Printed Page 130 Chapter Chronology

The British Empire and the Colonial Crisis, 1754-1775

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

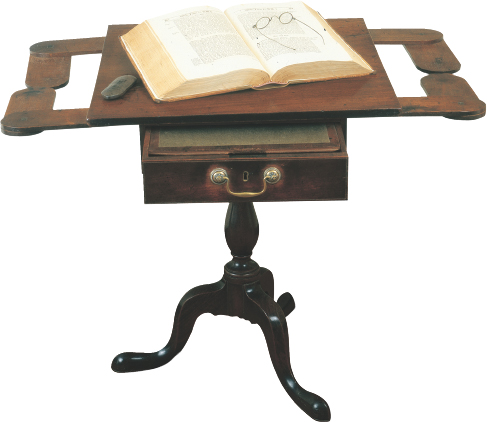

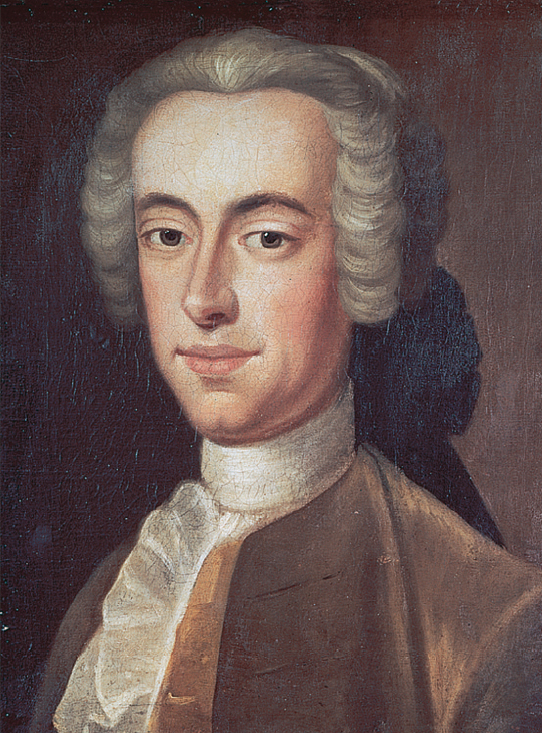

In 1771, Thomas Hutchinson became the royal governor of the colony of Massachusetts. Most royal governors were British aristocrats sent over by the king for short tours of duty, but Hutchinson was a fifth-generation American with a long record of public service in local institutions. He lived in the finest mansion in Boston; wealth, power, and influence were his in abundance. He was proud of his connection to the British empire and loyal to his king.

Hutchinson had the misfortune to be a loyal colonial leader during the two tumultuous decades leading up to the American Revolution. He worked hard to keep the British and colonists aligned in interests, even promoting a plan to unify the colonies with a limited government (the Albany Plan of Union) to deal with Indian policy. His plan of union ultimately failed, however, and a major war — the Seven Years' War — ensued, pitting the British and colonists against the French and their Indian allies in the backcountry of the American colonies. When the war ended and the British government proposed to tax colonists to help pay for it, Hutchinson was certain that the new British taxation policies were legitimate — unwise, perhaps, but legitimate.

Not everyone in Boston shared his opinion. Enthusiastic crowds protested a succession of taxation policies enacted after 1763, from the Sugar Act to the Tea Act. But Hutchinson maintained his steadfast loyalty to Britain. His love of order and tradition inclined him to unconditional support of the British empire, and by nature he was a measured and cautious man. "My temper does not incline to enthusiasm," he once wrote.

Privately, he lamented the stupidity of the British acts that provoked trouble, but his rigid sense of duty always prevailed, making him an inspiring villain to the emerging revolutionary movement. The man not inclined to enthusiasm unleashed popular enthusiasm all around him. He never appreciated that irony.

In another irony, Thomas Hutchinson early recognized the difficulties of maintaining full rights and privileges for colonists so far from their supreme government, the king and Parliament in Britain. At a crisis point in 1769, when British troops occupied Boston, he wrote privately to a friend in England, "There must be an abridgement of what are called English liberties. ...I doubt whether it is possible to project a system of government in which a colony three thousand miles distant from the parent state shall enjoy all the liberty of the parent state." He could not imagine the colonies without a parent state, existing independently.

Thomas Hutchinson was a loyalist, as were most English-speaking colonists in the 1750s. But the Seven Years' War, in which Britain and its colonies were allies, shook that affection, and imperial policies in the decade following the war shattered it completely. Over the course of 1763 to 1773, Americans insistently raised serious questions about Britain's governance of its colonies. Many came to believe what Thomas Hutchinson could never accept — that a tyrannical Britain had embarked on a course to enslave the colonists by depriving them of their traditional English liberties.

The opposite of liberty was slavery, a coerced condition of nonfreedom. Political rhetoric about liberty, tyranny, and slavery heated up the emotions of white colonists during the many crises of the 1760s and 1770s. But this rhetoric turned out to be a two-edged sword. The call for an end to tyrannical slavery meant one thing when sounded by Boston merchants whose commercial shipping rights had been curtailed, but the same call meant something quite different in 1775 when sounded by black Americans locked in the bondage of slavery.