Pontiac’s Rebellion and the Proclamation of 1763.

Printed Page 138 Chapter Chronology

Pontiac's Rebellion and the Proclamation of 1763. One glaring omission marred the Treaty of Paris: The major powers at the treaty table failed to include or consult the Indians. Minavavana, an Ojibwa chief of the Great Lakes region, put it succinctly to an English trader: "Englishman, although you have conquered the French, you have not yet conquered us! We are not your slaves. These lakes, these woods and mountains were left to us by our ancestors …; and we will part with them to none."

Indians north of the Ohio River had cause for concern. Old French trading posts all over the Northwest were beefed up by the British into military bases. Fort Duquesne, renamed Fort Pitt to honor the victorious leader, gained new walls sixty feet thick at their base, announcing that this was no fur trading post. Tensions between the British and the Indians in this area ran high.

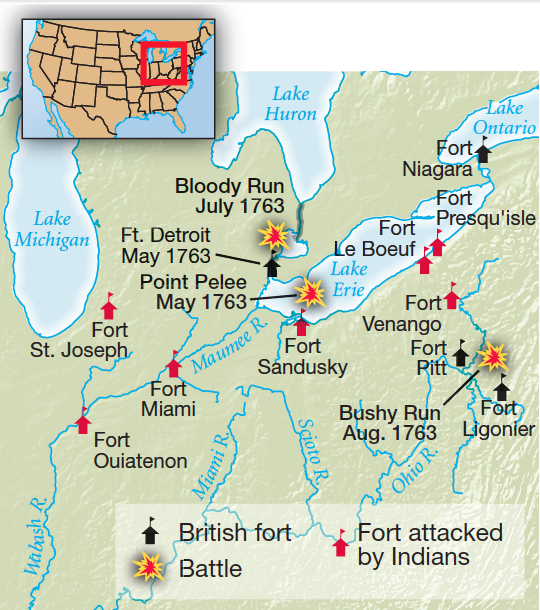

A religious revival among the Indians magnified feelings of antagonism toward the British. In 1763, the renewal of commitment to Indian ways and the formation of tribal alliances led to open warfare, which the British called Pontiac's Rebellion, named for the chief of the Ottawas. In mid-May, Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Huron warriors attacked Fort Detroit. Six more attacks on forts followed within weeks, and frontier settlements were raided by tribes from western New York, the Ohio Valley, and the Great Lakes region. By fall, Indians had captured every fort west of Detroit. More than four hundred British soldiers were dead and another two thousand colonists killed or taken captive.

Pontiac's Rebellion

A coordinated uprising of Native American tribes in 1763 in the Northwest after the end of the Seven Years' War. The rebellion heightened Britain's determination to create a boundary between Americans and Indians, embodied in the Proclamation of 1763.

Some Americans exacted revenge. The worst violent aggression occurred in late 1763, when some fifty Pennsylvania vigilantes known as the Paxton Boys descended on a peaceful village of friendly Conestoga Indians, murdering twenty. The vigilantes, now numbering five hundred, marched on Philadelphia to try to capture and murder some Christian Indians held in protective custody there. British troops prevented that, but the Paxton Boys escaped punishment for their murderous attack on the Conestoga village.

To minimize violence, the British government issued the Proclamation of 1763, forbidding colonists to settle west of the Appalachian Mountains in order to protect Indian territory. But the Proclamation's language also took care not to identify western lands as belonging to the Indians. Instead, it spoke of lands that "are reserved to [Indians], as their Hunting Grounds."

Other parts of the Proclamation of 1763 referred to American and even French colonists in Canada as "our loving subjects," entitled to English rights and privileges. By contrast, the Indians were rejected as British subjects and described more vaguely as "Tribes of Indians with whom We are connected." Of course, the British were not really well connected with any Indians, nor did they wish connections to form among the tribes. As William Johnson, the superintendent of northern Indian affairs, advised in 1764, "It will be expedient to treat with each nation separately ...for could they arrive at a perfect union, they must prove very dangerous Neighbours."

The Indian uprising had faded by early 1764, but the 1763 boundary was a further provocation to American settlers and also to land speculators who had already staked claims to huge tracts of western lands in hopes of profitable resale. Yet the boundary proved impossible to enforce. Surging population growth had already sent many hundreds of settlers, many of them squatters, west of the Appalachians. Periodic bloodshed continued and left the settlers fearful, uncertain about their future, and increasingly wary of British claims to be a protective mother country.