The New Nation Takes Form, 1789–1800

Printed Page 218 Chapter Chronology

The New Nation Takes Form,1789-1800

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

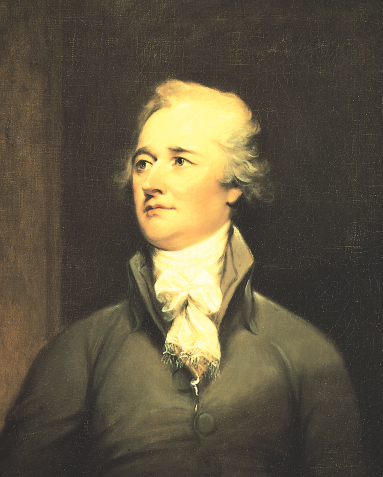

Alexander Hamilton, the man who brilliantly unified the pro-Constitution Federalists of 1788, headed the Treasury Department in the new government and thereby became the most polarizing figure of the 1790s.

Hamilton grew up on a small West Indies island, the son of an unmarried mother who died when he was eleven. He developed a fierce ambition to overcome his disadvantages and make good. After serving an apprenticeship to a trader, the bright lad made his way to New York City, where he soon gained entry to college. During the American Revolution, he wrote political articles for a newspaper that caught the eye of General George Washington, who was moved to select the nineteen-year-old to be his close aide. In the 1780s, Hamilton practiced law in New York and participated in the constitutional convention in Philadelphia. His shrewd political tactics greatly aided the ratification process.

A Cinderella story characterized Hamilton's private life too. Handsome and now well connected, he married a wealthy merchant's daughter. He had a magnetic charm that attracted both men and women; at social gatherings, he excelled. Late-night parties, however, never interfered with Hamilton's prodigious capacity for work.

As secretary of the treasury, Hamilton took quick action to build the economy. "If a Government appears to be confident of its own powers, it is the surest way to inspire the same confidence in others," he remarked. He immediately tackled the country's unpaid Revolutionary War debt, producing a complex proposal to fund the debt and pump millions of dollars into the U.S. economy. He drew up a plan for a national banking system to manage the money supply. And he designed a system of government subsidies and tariff policies to promote the development of manufacturing interests.

Hamilton was both visionary and practical, a gifted man with remarkable political intuitions. Yet this magnetic man made enemies; the "founding fathers" of the 1770s and 1780s became competitors and even bitter rivals in the 1790s. Both political philosophy and personality clashes created friction.

Hamilton's charm no longer worked with James Madison, now a representative in Congress and an opponent of all of Hamilton's economic plans. His charm had never worked with John Adams, the new vice president, who privately called him "the bastard brat of a Scotch pedlar" motivated by "disappointed Ambition and unbridled malice and revenge." Years later, when asked why he had deserted Hamilton, Madison coolly replied, "Colonel Hamilton deserted me." Hamilton assumed that government was safest when in the hands of "the rich, the wise, and the good" — by which he meant America's commercial elite. By contrast, agrarian values ran deep with Jefferson and Madison, and they were suspicious of get-rich-quick speculators, financiers, and manufacturing development.

The personal and political antagonisms of this first generation of American leaders left their mark on the young country. Leaders generally agreed on Indian policy in the new republic — peace when possible, war when necessary — but on little else. No one was prepared for the intense and passionate polarization over economic and foreign policy. The disagreements were articulated around particular events and policies: taxation and the public debt, a new treaty with Britain, a rebellion in Haiti, and a near war with France. At their heart, these disagreements sprang from opposing ideologies on the value of democracy, the nature of leadership, and the limits of federal power.

By 1800, the oppositional politics ripening between Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian politicians would begin to crystallize into political parties, the Federalists and the Republicans. To the citizens of that day, this was an unhappy development.