ETHNIC GROUPS AND GENETIC DISEASE

Ahern was not being irrationally fearful about getting cancer. She knew that both her family history and ethnic background put her at significantly increased risk. Ahern descends from a subgroup of Jews known as the Ashkenazi; the term generally refers to Jews of German and Eastern European descent. Ahern’s father was born in Germany, immigrating to the United States in 1939; her maternal grandfather was born in Russia.

The history of this Jewish subgroup extends much further back than modern Europe. The Ashkenazi Jews are a subgroup that left the Middle East and began populating parts of Europe more than 2,000 years ago. The majority of Ashkenazis migrated into Europe in the 10th century from the region of present-day Israel, settling in the Rhineland, the valley of the Rhine River, in Germany; from there, many migrated east into Poland and Russia.

A number of historical factors have made the Ashkenazi Jewish population more susceptible than others to genetic diseases. First, they descend from a small group of people. Second, that population has expanded and contracted over time. Third, and most important, members of the population usually marry within the community. In other words, Ashkenazi Jews have many of the characteristics of an isolated population into which new alleles are not frequently introduced by people immigrating into the population.

Consequently, Ashkenazi Jews are an example of an ethnic group that has a more homogeneous genetic background than the general population, and is more likely to pass on certain genetic diseases to future generations. Scientists have discovered more than 1,000 recessive diseases in the general population, but most of them are rare. In Ashkenazi Jews, however, the prevalence of some recessive diseases is increased 100-fold or more. Tay-Sachs disease, Gaucher disease, and Bloom syndrome are genetic diseases that all occur more frequently in this ethnic group than in the general population; approximately 1 in 25 Ashkenazi Jews carries disease alleles for at least one of these disorders (TABLE 10.1) .

| TABLE 10.1 | INCIDENCE OF HEREDITARY DISEASES IN DIFFERENT POPULATIONS |

| HEREDITARY DISEASE | CARRIER RATE IN ASHKENAZI JEWISH POPULATION | CARRIER RATE IN GENERAL POPULATION |

|---|---|---|

| Tay-Sachs disease | 1 in 25 | 1 in 250 |

| Canavan disease | 1 in 40 | Rare/unknown |

| Niemann-Pick disease, type A | 1 in 90 | 1 in 40,000 |

| Gaucher disease, type 1 | 1 in 14 | 1 in 100 |

| Bloom syndrome | 1 in 100 | Rare/unknown |

| BCRA mutation | 1 in 40 | 1 in 350–1,000 |

| Familial dysautonomia | 1 in 30 | Rare/unknown |

Ashkenazi Jews are not the only ethnic group to have a higher incidence of certain genetic diseases than occurs in the general population. For example, people from Mediterranean, African, and Asian countries have higher rates of thalassemias–blood disorders that cause anemia. Sickle-cell anemia, another type of hereditary anemia, is more common among people of African descent.

Ashkenazi Jews are also more likely than the general population to carry mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Some studies have found that more than 8% of Ashkenazi women carry a mutated BRCA1 gene, compared to only 2.2% of other women. These alleles can take the form of changes in one DNA base pair, or in several. In some cases, large DNA segments are rearranged. In mutated BRCA2 genes, a small number of additional DNA base pairs are inserted into or deleted from the gene.

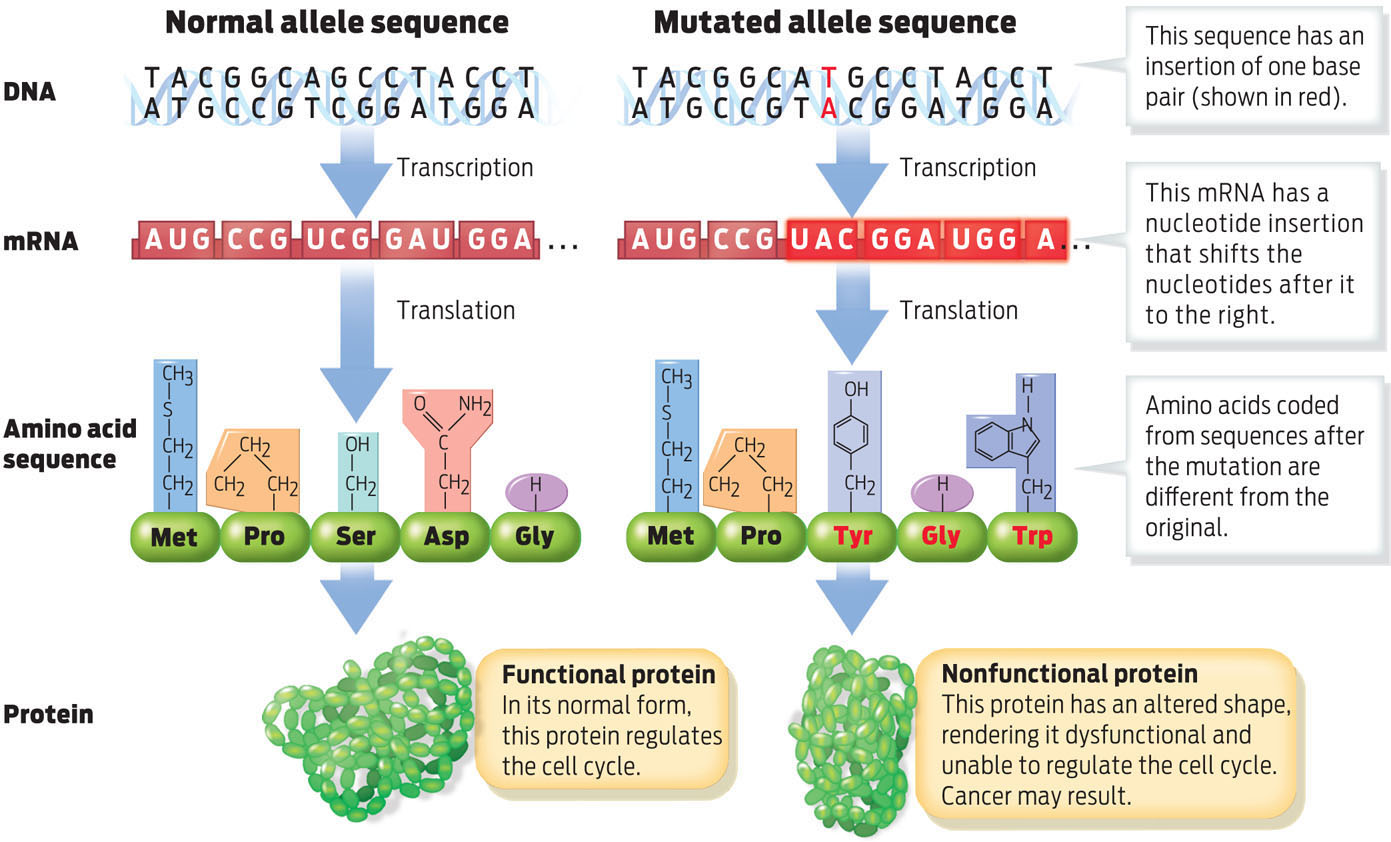

A change in the DNA sequence of a gene can cause problems if it alters the amino acid sequence of the corresponding protein. Because an altered amino acid sequence can also alter the shape of the protein, it can disable the protein and make it unable to perform its usual job. BRCA proteins produced from mutated alleles, for example, do not perform their job as cell cycle regulators, thus making cells more likely to divide uncontrollably and become cancerous. These altered proteins are what put Ahern at risk for cancer (INFOGRAPHIC 10.4) .

Mutations alter the nucleotide sequence of DNA. If a mutation changes the coding region of any gene, the corresponding protein may be dysfunctional. When the protein in question helps regulate the cell cycle, cancer may result.

219