NEW RESEARCH IN THE PIPELINE

For children who do inherit a genetic disease, there may be ways to treat the symptoms or reduce their severity. In the case of CF, new treatments are in the pipeline that could help Emily, and her children and grandchildren, too. Furthest along are a class of medications that, when inhaled, can restore the balance of ions inside affected cells in the lungs. Scientists are presently testing more than 20 experimental drugs in humans, and a few are already on the market.

Through basic research, scientists continue to learn more about cystic fibrosis. Over the past 25 years, scientists have discovered more than 1,000 different alleles of the CFTR gene. The most common is ?F508, which accounts for about 70% of all CF alleles. This particular CF allele is associated with more severe disease because it causes the CFTR protein to be absent from the cell membrane altogether.

Researchers have long puzzled over why the disease varies in two people with identical CF alleles—even two people who are both homozygous for the ?F508 allele may vary in how their disease progresses. Researchers long thought that perhaps environmental factors such as diet, social relationships, and exercise were responsible.

But in recent years, scientists have learned that there is more to the story. Researchers have discovered other genes on different chromosomes that contribute to the severity of CF symptoms. The genes so far discovered predominantly influence the immune system, which helps the body fight off infections.

241

For example, scientists have found that one allele of a gene called TGFßl, located on chromosome 19, is associated with more-severe lung disease in CF patients. This gene influences the immune response to infection. Scientists suspect that CF patients with certain TGFßl alleles mount a more vigorous response to infections than those with other alleles. Such a heightened immune response can cause lung tissue to scar. So if a CF patient also inherited this specific allele of TGFßl his or her lungs are more likely to scar in response to infections. The impact of such “modifier genes” on the CF phenotype makes it more complicated to assess how disabling any particular person’s CF disease will be—but it is not impossible.

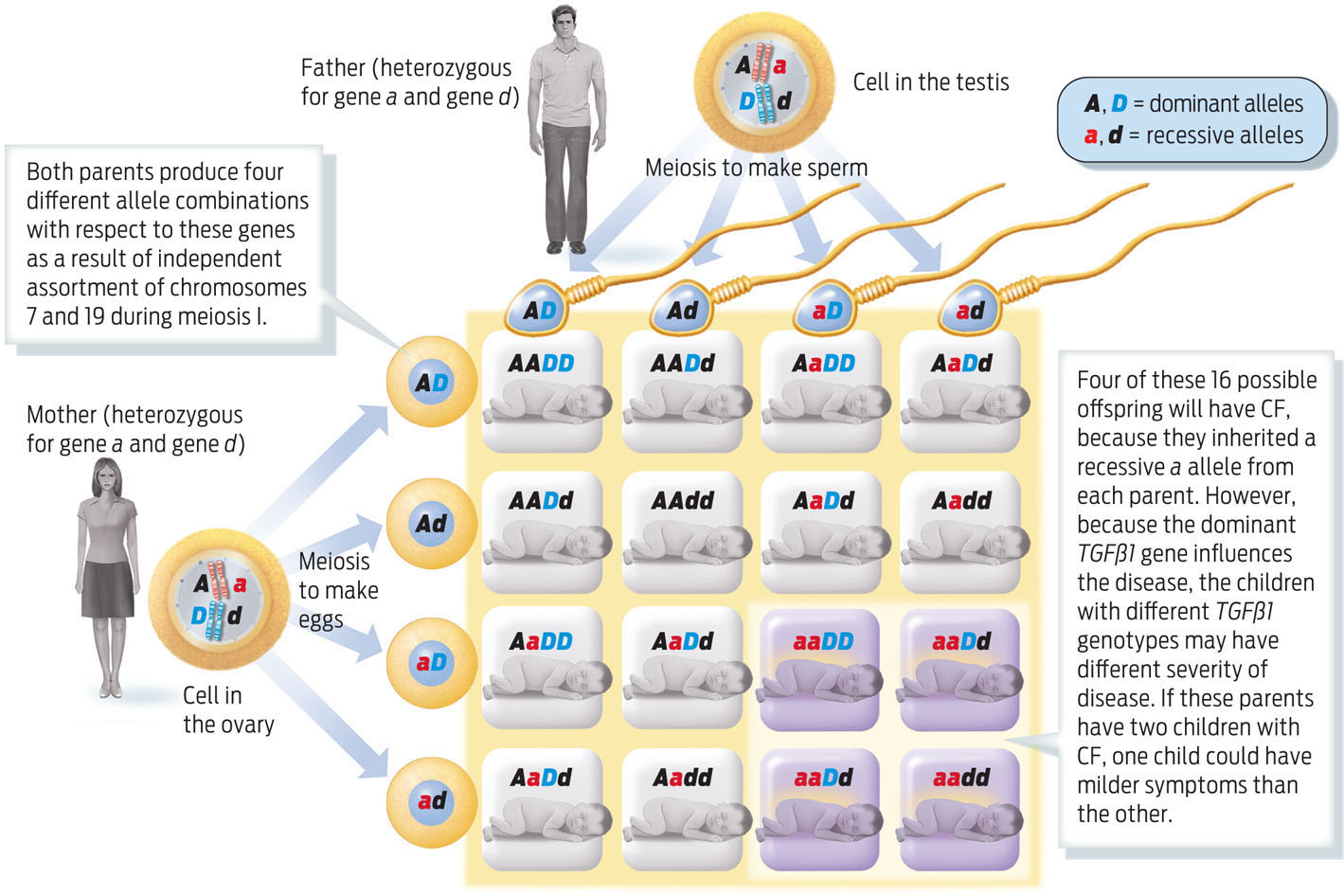

Parents who are heterozygous carriers of CF, for example, have a 1 in 4, or 25%, chance of having a child who has CF. If these two parents are also heterozygous for TGFßl, then the probability that their child will be homozygous recessive for TGFßl is also 1 in 4 (25%). The chance of two independent events occurring together is calculated by multiplying the two independent chances together. So the probability of being homozygous recessive for both CFTR and TGFßl is 1/4 × 1/4, or 1 in 16. This probability can also be calculated by using a Punnett square (INFOGRAPHIC 11.9) .

People with CF differ in the severity of their disease. Some of this variability is influenced by alleles of other genes that sit on other chromosomes. One such gene, TGFßl, is located on chromosome 19, shown here with symbol D. We can also use a Punnett square to follow the inheritance of two genes, as in the example below.

242

Over the past 25 years, scientists have discovered more than 1,000 different alleles of the CFTR gene.

Understanding how these modifier genes contribute to the disease may point the way to even more therapies. In some cases, existing drugs may prove useful. Drugs that reduce inflammation by targeting the TGFßl protein, for example, may help reduce scarring in the lungs.

Emily recently had her genotype tested. While she doesn’t carry ?F508, she does carry another allele associated with severe disease, G551D. This allele is much rarer than ?F508—only about 4% of the U.S. population has it. People with this mutation have a CFTR channel that doesn’t open properly. The good news for patients with this mutation is that a new FDA-approved drug, called Kalydeco, is remarkably effective at restoring function to their malfunctioning CFTR channel. Unlike other drugs, which merely treat the symptoms of the disease, this one addresses the underlying cause: the malfunctioning protein.

Kalydeco is not a cure for CF—the genetic mutation is still present in a person’s cells—but the drug allows patients to better control their symptoms. And that is enough for Emily. “Everyone talks about curing a disease—cure CF, cure these other diseases. [But] Kalydeco controls CF at the basic defect, so I’m OK with the other ‘c’ word, control, because I’m living it and I’ve never felt better in my life,” Emily recently told NPR. She nicknamed the drug “blue lightning,” because of how quickly the small blue pill helped her breathing.

Keenly aware of how medical progress has extended her life, Emily conducts her own share of fund raising and education. After that fateful New Year’s Eve when she and her friends opened for her brother’s band, South Normal, Hellen’s following grew. The band wrote more songs and refined their sound. “I favor the old stuff, AC-DC, Led Zeppelin, the Ramones,” Emily remarks. And fans just couldn’t seem to get enough of the girls’ sound. Each year, the number of fans has grown.

243

Sparked by a South Normal hit single called “Just Breathe,” Emily had the idea of organizing a concert to benefit CF research. The song has nothing to do with CF, but Emily thought that it might be a good theme for a concert. Besides, she says, “We were tired of walkathons and black tie events with tickets that cost $300 each.”

Emily and her brother organized the first benefit concert in 2004. Called “Just Let Me Breathe,” it featured four Detroit bands. The concert sold out and raised about $9,000. Inspired by that success, Emily decided to make the concert an annual event, and even persuaded Spin magazine to sponsor it. The benefit concert recently celebrated its seventh anniversary. With all her fund-raising activities, Emily has raised more than $300,000 so far. But she doesn’t plan on stopping there. In 2007, she started the Rock CF Foundation, a nonprofit devoted to improving the lives of people with cystic fibrosis and raising awareness of the disease. She continues to work actively with the foundation, even sponsoring and running in an annual half marathon. Her ultimate goal is simple, she says: to keep raising money and, one day, “Rock CF” for good.

244