Sex Determination

What makes a man?

What makes a man?

ANSWER: A botched circumcision in 1966 on a little boy named Bruce Reimer in time became a landmark example of how biology shapes sexual identity. Doctors at the hospital where Reimer was circumcised used an experimental procedure that involved burning off the foreskin. The procedure went awry, and Bruce’s penis was singed nearly completely off, beyond surgical repair. On the advice of John Money, a well-known psychologist and sex researcher at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, who had written much about the importance of environment in determining a person’s sexual identity, Bruce’s parents decided to have their little boy surgically turned into a little girl and rear him as “Brenda.”

But Brenda never behaved like a girl. She didn’t like playing with girls’ toys, didn’t enjoy wearing dresses, and often got into fistfights at school. By the time Brenda reached puberty, her behavior became so troublesome that her father broke down and told her what had happened to her. Brenda felt relieved rather than angry. “All of a sudden everything clicked,” she later said. “For the first time things made sense and I understood who and what I was.”

Brenda eventually had reconstructive surgery to create a penis, took hormones, and changed her name to David. David told his story in a book published in 2000, As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as a Girl, by John Colapinto. By that time, it had become increasingly clear that sexual identity—the experience of oneself as male or female—is significantly influenced by biology. Studies had shown that prenatal exposure to fetal sex hormones such as testosterone not only determine whether a fetus will develop female or male genitalia, but also act on a developing baby’s brain, influencing behavior.

257

258

GONADS Sex organs: ovaries in females, testes in males.

AUTOSOMES Paired chromosomes present in both males and females; all chromosomes except the X and Y chromosomes.

Sex hormones are produced by sex organs known as the gonads—ovaries in females, testes in males. Sex hormones include androgens (from andros, Greek for “man”), such as testosterone, and estrogen (from the Greek oistros, meaning “mad passion”). Both males and females produce testosterone and estrogen, but in most cases males produce higher levels of testosterone and females produce higher levels of estrogen. In a developing fetus, these hormones shape the development of both internal and external sexual anatomy.

SEX CHROMOSOMES Paired chromosomes that differ between males and females, XX in females, XY in male

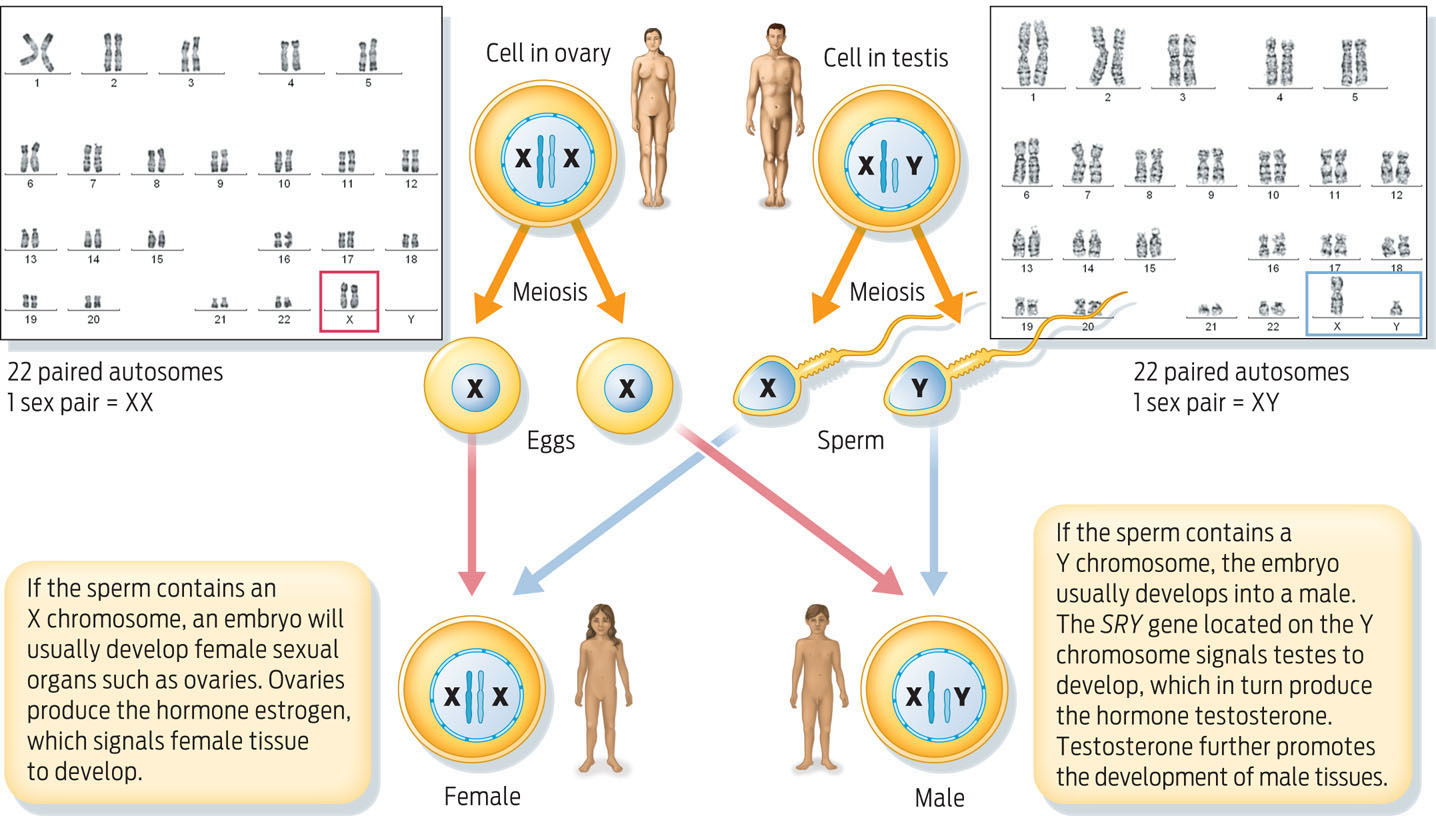

Whether a fetus develops male or female gonads, and produces male or female hormones, depends on the set of chromosomes it receives from its parents. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes; 22 pairs are autosomes and 1 pair are the sex chromosomes, X and Y. Sons inherit one Y chromosome from their father and one X chromosome from their mother. Daughters inherit two X chromosomes, one each from mother and father. So males are XY and females are XX. In the absence of a Y chromosome, a fetus will develop into a female. Thus, fathers determine the sex of a baby, the determination based on whether the sperm fertilizing a mother’s egg carries an X or a Y sex chromosome. The Y chromosome contains a gene called SRY that signals testes to develop. (SRY stands for “sex-determining region on the Y chromosome.”) The testes, in turn, produce masculinizing hormones such as testosterone that mold a male body (INFOGRAPHIC 12.1) .

Maies and females differ by virtue of a pair of sex chromosomes. Females have two X chromosomes and males have a single X and a single Y chromosome. Every person must have at least one X chromosome, but it’s the presence of a gene on the Y chromosome that initiates male development.

259

Although most individuals have internal and external genitalia that are either clearly male or clearly female, there are exceptions. Each year about 1 in every 1,600 babies born in America falls into an intermediate sex category termed “intersex.” An intersexual person is someone whose external genitalia do not match his or her internal sex organs or genetic sex—for example, a person with an XX chromosome pair who has internal ovaries but external genitalia that appear male. Often intersex babies are born with ambiguous genitalia.

Debate over the experience of David Reimer, and similar cases, as well as research showing how strongly biology influences sexual identity, has changed the care of intersex babies. Today, such babies are often assigned a sex by parents and doctors only after a period of observation to assess behavior patterns. Surgeons then perform surgery to create either male or female genitalia. Or, parents may forgo surgery, preferring that their child remain as is.

Some instances of intersex have genetic causes. For example, if the Y chromosome has a mutation in the SRY gene, the embryo is likely to have undeveloped gonads with external female genitalia, even though it carries an XY chromosome pair.

There are also cases of people with XY sex chromosomes who have mutations in genes that code for androgen receptors on cells. So even though they carry a functional SRY gene and have internal testes, their cells fail to respond to androgens like testosterone. As a result, complete male external genitalia do not develop, and these people appear to be female.

Similarly, there are people with XX sex chromosomes who have male genitalia. In some cases, this is caused by a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia. These individuals have one or more mutations in genes on autosomal chromosomes. One result is excessive production of androgens. These people have ovaries but may have genitals that appear more male than female.

Some people have only one sex chromosome, while others have three. Every person must have at least one X chromosome (having none is fatal), but because of errors in chromosome segregation during meiosis, a variety of other X and Y combinations are possible: XXY men, women with only a single X chromosome, XXX females, and XYY males. In many of these cases, a person’s physical traits and genitalia reveal that they do not have the usual makeup of sex chromosomes, but not always (TABLE 12.1) .

260

| TABLE 12.1 | BETWEEN MALE AND FEMALE: VARIETIES OF SEX AND INTERSEX |

| SEX CATEGORY | CHROMOSOMES | GONADS | GENITALIA | OTHER CHARACTERISTICS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | XX | Ovaries | Female | |

| Male | XY | Testes | Male | |

| Female pseudohermaphroditism | XX | Ovaries | Male | Infertile |

| Male pseudohermaphroditism | XY | Testes | Female or ambiguous | Infertile |

| True gonadal Intersex | XX and/or XY | ovaries and testes | Male, female, or ambiguous | Infertile; historically called true hermaphrodites |

| Triple X syndrome | XXX | Ovaries | Female | Fertile, taller than average, learning disabilities |

| Klinefelter syndrome | XXY | Testes | Male | Infertile, enlarged breast tissue |

| 47, XYY syndrome | XYY | Testes | Male | Fertile, taller than average, elevated risk for learning and emotional disabilities |

| Turner syndrome | X | Ovaries | Female | Infertile, broad chest, webbed neck |

As you can see, sex isn’t so easy to define; there are genetic, hormonal, anatomical, and behavioral aspects to sex, and these elements don’t always align. Defining what counts as “masculine” and “feminine” is even more complicated. For example, some men have characteristics that we typically identify as female, such as a high voice and sparse body hair, yet they are genetically and anatomically male. And many women have what are considered to be more masculine features, such as angular faces and more muscle as compared to body fat. Yet, they are genetically and anatomically female. In fact, there are very few physical or mental characteristics that are entirely male or entirely female. In addition, some people—for example, transgender individuals—may mentally identify with one sex even though their genitalia and chromosomal makeup classify them as the other.

For biologists, the story of David Reimer—known in the medical literature as the “John/Joan case”—put the nail in the coffin of the idea that children are born psychosexually “neutral.” Contrary to what sex researcher Money and others had claimed, it was not possible to mold someone into whichever sexual identity you wanted through surgery and child rearing—at least not without damaging psychological fallout. Of this stubborn fact, David Reimer was living proof.

David eventually married a woman and adopted her three children. Though he could not have children of his own (since his testes had been removed), he took the responsibilities of fatherhood seriously. “From what I’ve been taught by my father,” he told Colapinto, “what makes you a man is: You treat your wife well. You put a roof over your family’s head. You’re a good father…That, to me, is a man.”

David said he told his story so that others would be spared the nightmarish experience he went through. Tragically, that experience may have led to the depression that cost him his life. David killed himself in 2004. He was 38.

261