330

DRIVING QUESTIONS

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- What is a gene pool (and can you swim in it)?

- How do different evolutionary mechanisms influence the composition of a gene pool?

- How does the gene pool of an evolving population compare to the gene pool of a nonevolving population?

- How do new species arise, and how can we recognize them?

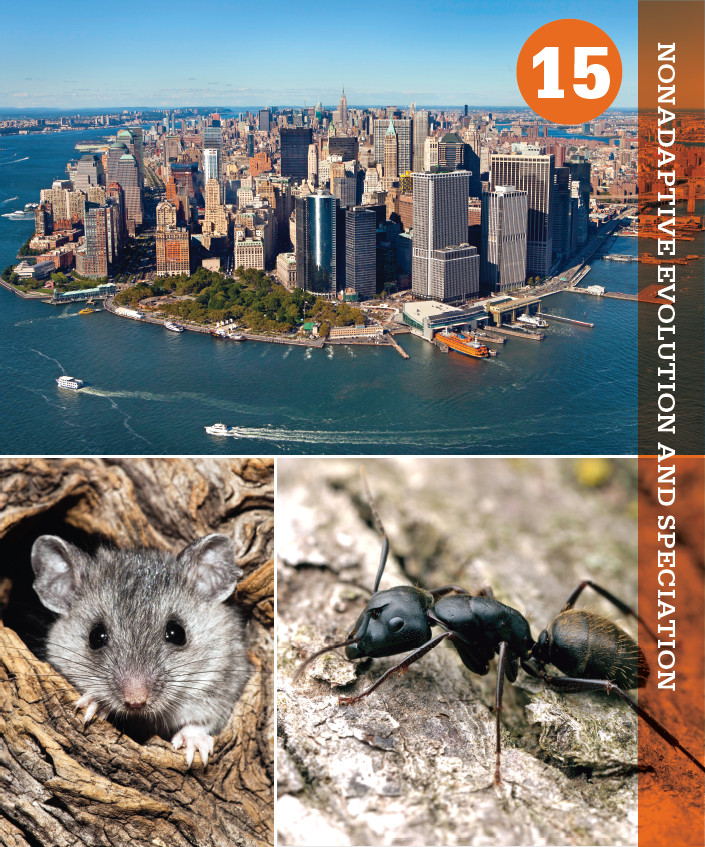

N A SOGGY DAY IN 2012, BIOLOGISTS JASON MUNSHI-SOUTH and Stephen Harris traipse through the underbrush of Highbridge Park in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan, some 8 miles north of Times Square. They brush back a swatch of green to reveal a small, shoebox-size trap, with one unhappy camper inside: a tiny white-footed mouse. This diminutive rodent, only about 2 inches long, is one of a few urban species that scientists have begun to look at more closely for answers to questions about evolution.

N A SOGGY DAY IN 2012, BIOLOGISTS JASON MUNSHI-SOUTH and Stephen Harris traipse through the underbrush of Highbridge Park in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan, some 8 miles north of Times Square. They brush back a swatch of green to reveal a small, shoebox-size trap, with one unhappy camper inside: a tiny white-footed mouse. This diminutive rodent, only about 2 inches long, is one of a few urban species that scientists have begun to look at more closely for answers to questions about evolution.

Studying evolution in Manhattan—arguably the most unnatural place on the planet—might seem an odd choice. But Munshi-South and Harris belong to a new breed of biologist, one fascinated by the nature right under our noses. From rodents in parks to ants on median strips to the cockroaches and bedbugs inside buildings—even the bacteria brewing inside our belly buttons—no location is too mundane for this scientific crew.

What’s the advantage of staying local? Besides being quite convenient—Munshi-South and Harris work at Baruch College in midtown Manhattan—cities like New York offer some unique opportunities for the evolutionary biologist.

331

332

“There isn’t really anywhere on the planet that isn’t impacted by human activity now,” says Munshi-South. “If we want to understand how species are actually evolving now, we need to understand the inputs from human activity.”

And nowhere is that input more evident than in the Big Apple. With a population of 8 million people packed into just 300 square miles of land, New York City is the largest and most densely populated city in the United States. All those restless urbanites have left a profound mark on the landscape, changing it in both dramatic and subtle ways. Just look at Manhattan, New York City’s most densely populated borough: Once an island of thick forest, Manhattan is now a sliver of concrete, interspersed with oases of green. The skyscrapers, the bridges, the subway system—not to mention the bars and coffee shops—have all transformed a once wild place beyond recognition. In the process, says Munshi-South, the city’s wildlife has been subject to “a grand evolutionary experiment.”