A GREEN WORLD

Olympic’s unique collection of wildlife reflects the geological history and ecology of the region. During the last ice age, approximately 20,000 years ago, the Olympic Peninsula was isolated by glaciers and largely separated from the rest of what is now the United States. Today, it is surrounded by saltwater on three sides and is essentially an ecological island, distinctive in its geography and topography.

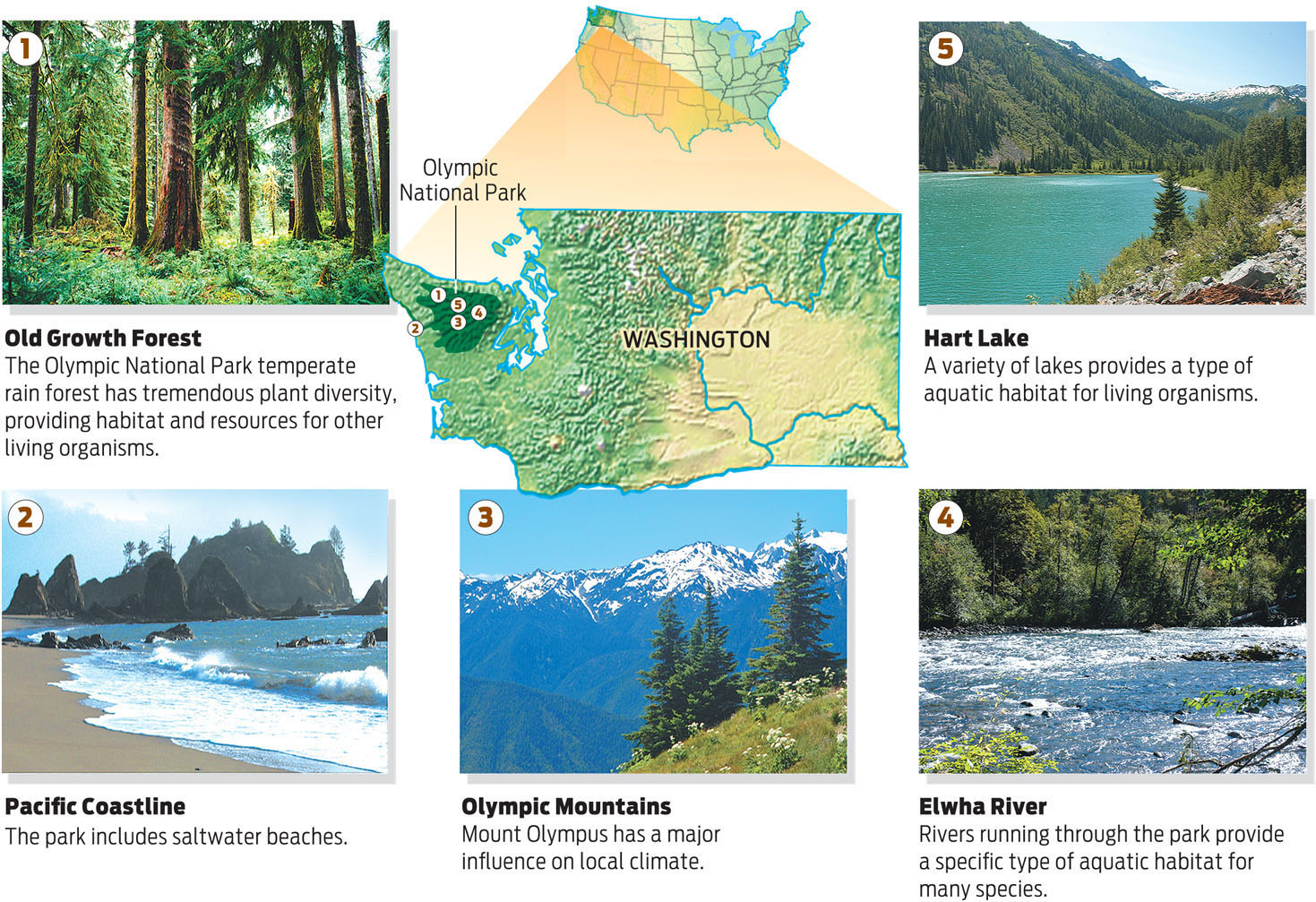

Far from being a single landscape, however, Olympic National Park is more like three parks in one: a glacier-topped mountain region with flowering subalpine meadows, valleys of temperate rain forest threaded with freshwater rivers and lakes, and nearly 60 miles of jagged Pacific coastline. Central to the park’s ecology is the towering presence of Mount Olympus, a nearly 10,000-foot peak that traps warm air blowing in from the Pacific, making the western slope one of the wettest spots in the United States: it’s doused in more than 12 feet of rain each year. This mosaic of physical, geographic, and climatic conditions provides numerous habitats for the many species of eukaryotes that live here (INFOGRAPHIC 19.2) .

Olympic National Park has an enormous diversity of physical, geological, and climatic conditions, all of which contribute to the huge biological diversity in the park.

414

PLANT A multicellular eukaryote that has cell walls, carries out photosynthesis, and is adapted to living on land.

Each segment of the park is marked by its distinct form of vegetation, or plant life. Within the low-elevation rain forests, for example, stands of giant Sitka spruce and Douglas fir trees form a thick canopy of green, steadily dripping moisture. In dense forest understory, 300 feet below the canopy, plants form a junglelike tangle: nearly every log and tree trunk is coated with a shaggy carpet of mosses, ferns, and lichens (lichens are partnerships between a fungus and a photosynthetic organism), while hanging plants drape on branches like luxurious scarves with long ground-reaching stems.

In all this variety, how can scientists differentiate plants from other eukaryotes, like protists or fungi? At the most basic level, a plant is a multicellular eukaryote that possesses cells with cell walls, carries out photosynthesis, and is adapted to living on land. Plants such as those found in Olympic first evolved from water-dwelling algae about 450 million years ago, when life on Earth was confined primarily to the seas. As plants radiated and diversified on land, they evolved a number of adaptations that made them increasingly independent of water.

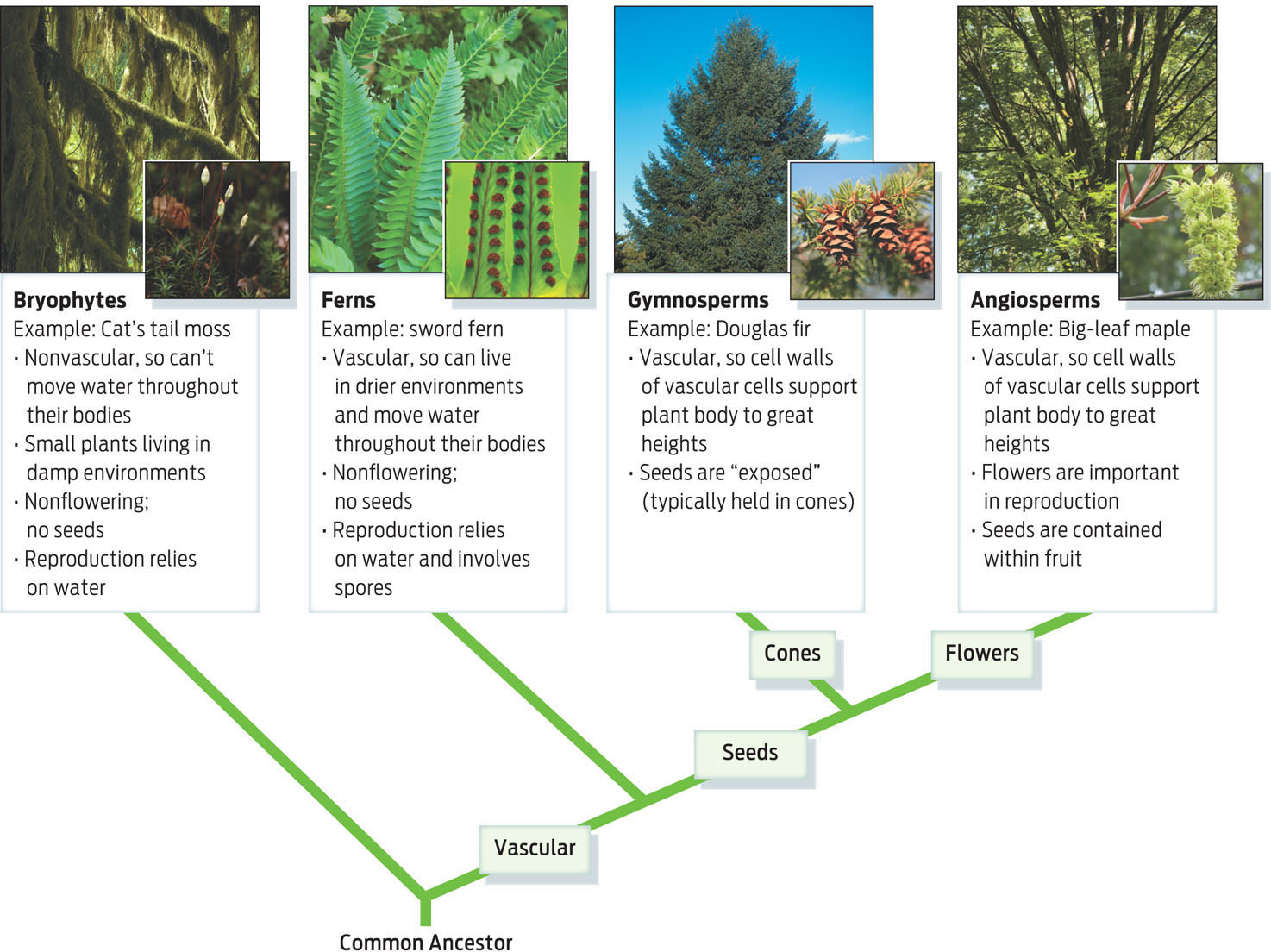

BRYOPHYTE A nonvascular plant that does not produce seeds.

415

VASCULAR PLANT A plant with tissues that transport water and nutrients through the plant body.

The earliest plants that made the transition from water to land were small, seedless plants called bryophytes. Bryophytes lack roots and tissue for transporting water and nutrients throughout their bodies, and therefore can grow only in damp environments, where they can easily absorb water. One of the wettest places on Earth, the Olympic rain forest is a soggy paradise for bryophytes, such as mosses and liverworts, which appear as squat, spongy mats.

FERN The first true vascular plants; ferns do not produce seeds.

The rain forest is also home to many vascular plants—those with specialized tissues for transporting nutrients and water through the plant body. The first true vascular plants were ferns, such as the hip-high sword ferns that cover a good portion of the Olympic forest. Like bryophytes, ferns do not produce seeds. Yet unlike those vertically challenged relatives, ferns can stand upright and grow tall, thanks to the vascular tissue that keeps stems rigid and transports water and nutrients from the plant’s roots to its leaves. At one time, ferns ruled the plant world, spreading their massive fronds across the entire landscape in the Carboniferous period. But their reign was short lived. Soon, another kind of plant evolved to challenge the ferns’ dominance: those with seeds.

ANGIOSPERM A seed-bearing flowering plant with seeds typically contained within a fruit.

Seed plants first emerged about 360 million years ago, during the late Devonian Period. A seed, which envelops a plant’s embryo, is an ideal package for withstanding harsh conditions and transporting the embryo to a location where it can grow into a new plant. Seed plants were so successful that they quickly came to dominate forests by the time dinosaurs appeared in the Mesozoic Era.

GYMNOSPERM A seed-bearing plant with exposed seeds typically held in cones.

Today, more than 90% of all living plants are seed plants. Angiosperms are flowering plants with seeds contained in a fruit–an apple, say, or an acorn (“angio” is from the Greek for “vessel” or “container”). Olympic National Park is home to many species of angiosperms, including oaks, maples, huckleberry bushes, and willows, as well as hundreds of species of flowers. Plants with exposed seeds, as in a pinecone, are known as gymnosperms—spruce, pine, redwood, fir, and other conifers, for example. (Gymnos is Greek for “naked,” so the name literally means “naked seeds.”) (INFOGRAPHIC 19.3)

All plants have evolved from an ancient common ancestor. Different groups of plants have developed different specializations that allow them to be successful on land.