A Forest for Fishers (And More)

Olympic National Park is an especially good home for the tree-loving fisher (Martes pennanti). “Because the park is 95% wilderness area, little of it has been logged, and it contains great expanses of older forest, which provide the large trees, snags, and logs that fishers need,” says Lewis. Fishers rest in nooks in the trees, and females use tree cavities as dens in which to birth and nurse their kits. The shy fishers are also attracted to places with dense canopy cover, woody debris, and understory vegetation, all of which provide plentiful hiding places. Many of the tree species found here make for prime fisher habitat, including western Hemlock, Sitka spruce, and Pacific silver fir, which also provide a reliable food source for seed- and insect-eating mammals that fishers stalk as prey, such as squirrels, mice, and shrews.

ANIMAL A eukaryotic multicellular organism that obtains nutrients by ingesting other organisms.

416

The fisher is an animal, of course, but what defines an animal? Scientifically, an animal is a multicellular eukaryotic heterotroph that obtains nutrients by ingestion–that is, by eating. When we humans think of “animal,” we tend to picture mammals, such as the fur-covered fisher. But the term applies to a great variety of creatures, from sponges to worms to insects to humans. To help bring some order to this diversity, biologists sort animals into smaller groups on the basis of shared characteristics and ancestry.

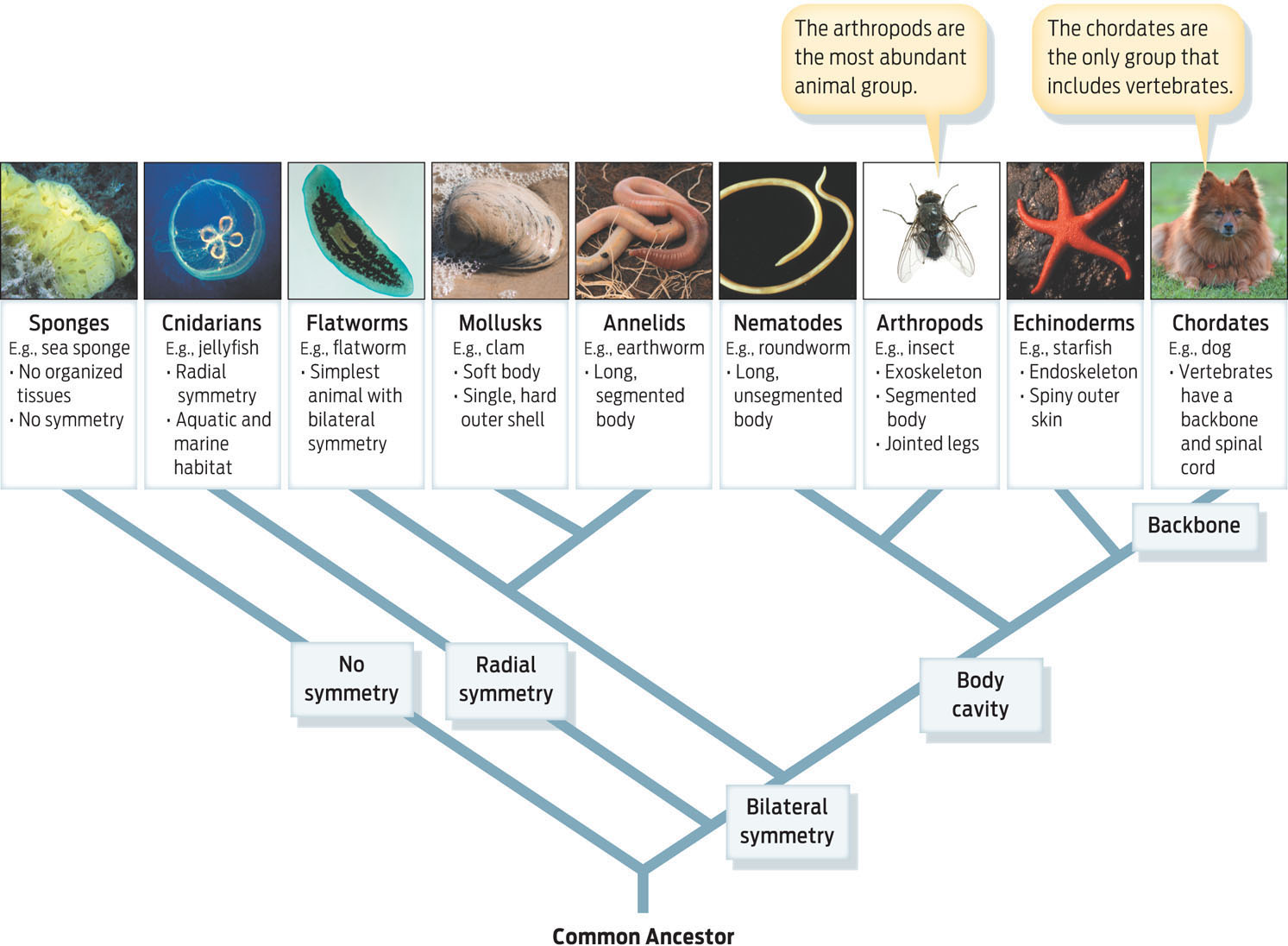

Many features can be used to group and sort animals. Historically, biologists relied mostly on anatomical and embryological evidence, but in recent years it has become more common to use genetic evidence. From genetic evidence, it is clear that all animals descend from a common ancestor that lived nearly 1 billion years ago and whose descendants diversified into the different forms we see today.

RADIAL SYMMETRY The pattern exhibited by a body plan that is circular, with no defined left and right sides.

Early in their history, animals branched into three main lineages, and the legacy of that division can be seen in three distinct animal body plans in existence today. The simplest living animals, such as sponges, lack defined tissues or organs and are amorphous—that is, they have no definite shape. These asymmetrical organisms are likely similar to the earliest animals to have populated the oceans. All other animals have defined tissues and fall into one of two broad categories based on the type of body symmetry they possess.

BILATERAL SYMMETRY The pattern exhibited by a body plan with right and left halves that are mirror images of each other.

Animals such as jellyfish and coral exhibit radial symmetry, meaning that they’re shaped like a pizza—circular, with no defined left and right sides. All other animals—every-thing from worms and insects to fishers and humans—exhibit bilateral symmetry: if you cut them down the middle you produce left and right halves that are mirror images of each other.

VERTEBRATE An animal with a bony or cartilaginous backbone.

Bilateral symmetry has become very prevalent in the animal kingdom because it is a useful adaptation for seeking out food, stalking prey, and avoiding predators. For instance, bilaterally symmetrical animals have an eye on each side of the face, enabling them to look straight ahead. In the fisher’s case, such bilateral symmetry enables it to climb down trees head first in search of prey.

INVERTEBRATE An animal lacking a backbone.

Fishers, members of the phylum Chordata, are vertebrates, meaning they are animals with a backbone. A fisher’s backbone is made of bony vertebrae, a feature they share with most other vertebrates. (A few vertebrates, primarily sharks and several other fish, have backbones made of cartilage.) While vertebrates—which include humans—are some of the most easily recognized animals, they represent a sliver of the total animal world. In fact, most animals lack a backbone and are therefore called invertebrates. While invertebrates are often lumped together on the basis of what they lack, the division of the animal world into those with and those without backbones makes about as much sense as dividing the world into sponges and nonsponges—it overlooks a lot of differences, and obscures the fact that most animals—an astounding 95%—are invertebrates (INFOGRAPHIC 19.4) .

417

All animals have descended from a common ancestor. Many features help classify animals, including body symmetry, type of body support, and the presence or absence of a spinal cord and backbone. In addition, genetic sequencing and the study of embryonic development have informed this phylogenetic tree.

MOLLUSK A soft-bodied invertebrate, generally with a hard shell (which may be tiny, internal, or absent in some mollusks).

Olympic National Park hosts a squirming, wriggling, buzzing swarm of invertebrates. If you were hiking or camping in the park, you would easily encounter invertebrates from several major phyla–some more welcome than others, perhaps.

Sliding quietly amid leaf litter on forest trails are many specimens of the Pacific coast’s best known mollusk, the brightly colored banana slug (one of the few invertebrates to serve as a university mascot, as it does for the University of California at Santa Cruz). A squishy yellow creature that can grow nearly to the size of its namesake fruit, the banana slug is one of the forest’s most voracious inhabitants, eating its way through just about everything in its path, from animal carcasses and droppings to mushrooms, lichens, and leaves. This mollusk is so successful in the forest in part because it is distasteful to would-be predators, who know by its unmistakable color to avoid eating it.

418

ANNELID A segmented worm, such as an earthworm.

Slugs—and their shelled cousins, the snails—are often considered garden pests. Yet by digesting dead plant material, these mollusks help recycle nutrients. And with their calcium-rich shells, snails provide this valuable mineral to the creatures that feast on them, such as rodents and birds. Some humans find mollusks a tasty treat as well: if you have enjoyed clams, oysters, or squid, then you have eaten some aquatic varieties of mollusk.

ARTHROPOD An invertebrate having a segmented body, a hard exoskeleton, and jointed appendages.

Campers in Olympic who move rocks to pitch their tents or dig holes to act as their toilets likely uncover numerous squirmy annelids, or segmented worms. Annelids such as earthworms perform a critical ecological service by creating passageways in the soil as they move around. The passageways allow air and water to enter the soil, which is important for plants and other aerobic organisms that require water and oxygen. By eating and digesting leaf and other plant litter, earthworms also make nutrients available for other plants.

EXOSKELETON A hard external skeleton covering the body of many animals, such as arthropods.

The park is also home to an enormous collection of arthropods. Arthropods are the most abundant invertebrates in the park, and on Earth in general. There are an estimated 2-4 million species of arthropods, of which 855,000 have been officially described so far. The number of individual arthropods on the planet is estimated to be more than 1018 (that’s 1 with 18 zeros after it). They include animals as diverse as water-dwelling crustaceans like crabs and lobsters and terrestrial spiders, millipedes, and flying insects.

ENDOSKELETON A solid internal skeleton found in many animals, including humans.

Despite their abundance and diversity, all arthropods share some common physical characteristics. They have segmented bodies with jointed appendages such as legs, antennae or pincers, and a hard exoskeleton, or external skeleton, made up of proteins and chitin (a type of polysaccharide). An arthropod’s exoskeleton serves multiple functions: it protects the organism from predators, keeps it from drying out, and provides structure and support for movement, just as our internal endoskeleton does.

INSECT A six-legged arthropod with three body segments: head, thorax, and abdomen.

Most arthropods are harmless or even helpful to humans, but some are not. A few produce powerful venoms that can be deadly when they are conveyed to victims through bites or stings.

The vast majority of all arthropods are insects—arthropods with three pairs of jointed legs and a three-part body consisting of head, thorax, and abdomen. Insects include animals like the honey bees and butterflies that pollinate flowers, the termites and cockroaches that infest our walls, and those blood-sucking insects hated by campers everywhere: mosquitoes. Insects are evolution’s great success story. Having first evolved some 400 million years ago, there are now more insect species on the planet than all other animals species combined.

Insect bodies boast an array of useful adaptations, including three-pronged mouthparts that are used variously for biting, chewing, or sucking. But what really sent insect diversity soaring was the evolution of wings. Wings enable insects to fly away from predators, access distant food sources, and travel to find mates. Among the most successful of all flying insects are beetles, which have two sets of wings and mouthparts specialized for biting, mincing, or chewing. Taxonomists have catalogued approximately 350,000 beetle species so far, and some estimates put the total number of species in the millions.

But even insects with six feet firmly planted on the ground can be remarkably successful–just look at the ants. They can’t fly, but they can communicate, split up tasks, solve problems, and shape their local environment—a picnic, for example—for their own needs. Given their complex social behavior and adaptations, it’s not surprising to find ants nearly everywhere on the planet; Antarctica, Greenland, Iceland, and Hawaii are some of the few places on Earth believed to harbor no native ant species.

419

They are occasionally killed by cougars, coyotes, and eagles, but the fishers’ biggest foes, by far, are humans.