xx

1

DRIVING QUESTIONS

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- How is the scientific method used to test hypotheses?

- What factors influence the strength of scientific studies and whether the results of any given study are applicable to a particular population?

- How can you evaluate the evidence in media reports of scientific studies?

- How does the scientific method apply in clinical trials designed to investigate important issues in human health?

In-Class Activity

Click here to access Lecture ppt specifically designed for chapter 1.

Click here to access Clicker Questions specifically designed for chapter 1.

N 1981, A STUDY IN THE PROMINENT New England Journal of Medicine made headlines when it reported that drinking two cups of coffee a day doubled a person’s risk of getting pancreatic cancer. Drinking five cups a day supposedly tripled the risk. “Study Links Coffee Use to Pancreas Cancer,” trumpeted the New York Times. “Is there cancer in the cup?” asked Time magazine. The lead author of the study, Brian MacMahon of the Harvard School of Public Health, appeared on the Today show to warn of the dangers of coffee.

N 1981, A STUDY IN THE PROMINENT New England Journal of Medicine made headlines when it reported that drinking two cups of coffee a day doubled a person’s risk of getting pancreatic cancer. Drinking five cups a day supposedly tripled the risk. “Study Links Coffee Use to Pancreas Cancer,” trumpeted the New York Times. “Is there cancer in the cup?” asked Time magazine. The lead author of the study, Brian MacMahon of the Harvard School of Public Health, appeared on the Today show to warn of the dangers of coffee.

“I will tell you that I myself have stopped drinking coffee,” said MacMahon, who had previously drunk three cups a day.

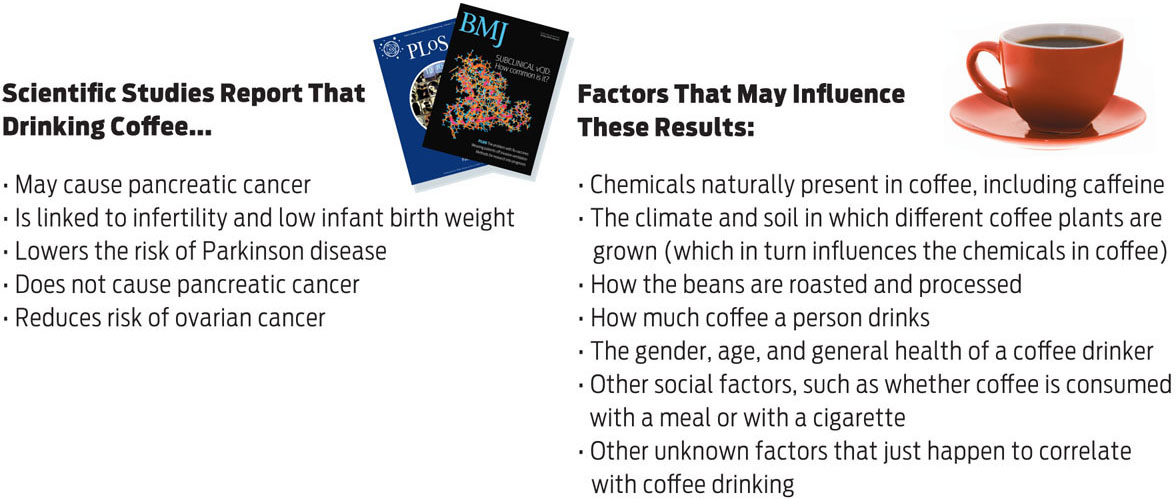

Just 5 years later, MacMahon’s research group was back in the news, reporting in the same journal that a second study had found no link between coffee and pancreatic cancer. Subsequent studies by other researchers also failed to reproduce the original findings.

2

Today, more than 30 years later, coffee is once again making headlines. Recent studies have suggested that, far from causing disease, coffee may actually help prevent a number of conditions—everything from Parkinson disease and diabetes to cancer and tooth decay. “Java Junkies Less Likely to Get Tumors,” announced a 2010 CBS News headline. “Morning Joe Fights Prostate Cancer,” proclaimed a blog. The September 2010 issue of Prevention magazine ran an article titled “Four Ways Coffee Cures,” itemizing supposed health benefits for each additional cup consumed.

Not everyone is buying the coffee cure, however. Public health advocates are increasingly alarmed by our love affair with—some might say, addiction to—caffeine. Emergency rooms are reporting more caffeine-related admissions, and poison control centers are receiving more calls related to caffeine “overdoses.” In response, politicians are pressuring the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to force manufacturers to place warning labels on energy drinks. Nevertheless, caffeine’s “energizing” effect is advertised on nearly every street corner, where, increasingly, you’re also likely to find a coffee shop. As of 2012, according to Foodio54.com, there were 231 Starbucks within a 5-mile radius of a Manhattan zip code; nationally, the average within the same radius is 10.

Why the mixed messages about caffeine? Are researchers making mistakes? Are journalists getting their facts wrong? While both of these possibilities may be true at times, the bigger problem is widespread confusion over the nature of science and the meaning of scientific evidence.

“Consumers are flooded with a firehose of health information every day from various media sources,” says Gary Schwitzer, publisher of the consumer watchdog site HealthNewsReview.org and former director of health journalism at the University of Minnesota. “It can be—and often is—an ugly picture: a bazaar of disinformation.” Too often, he says, the results of studies are reported in incomplete or misleading ways.

Why might consuming coffee or caffeine be associated with such dramatically different results? The risks or benefits of a caffeinated beverage may depend on the amount a person drinks—one cup versus a whole pot. Or maybe it matters who is drinking the beverage. The New England Journal of Medicine study, for example, looked at hospitalized patients only. Would the same results have been seen in people who weren’t already sick? Sometimes, to properly evaluate a scientific claim, we need to look more closely at how the science was done (INFOGRAPHIC 1.1) .

A variety of studies published in peer-reviewed scientific journals report different conclusions about the risks and benefits of coffee. In order for the public to understand and use these outcomes to its advantage, a closer look at the scientific process and the factors that surround coffee drinking is necessary.