SCIENCE IS A PROCESS

SCIENCE The process of using observations and experiments to draw conclusions based on evidence.

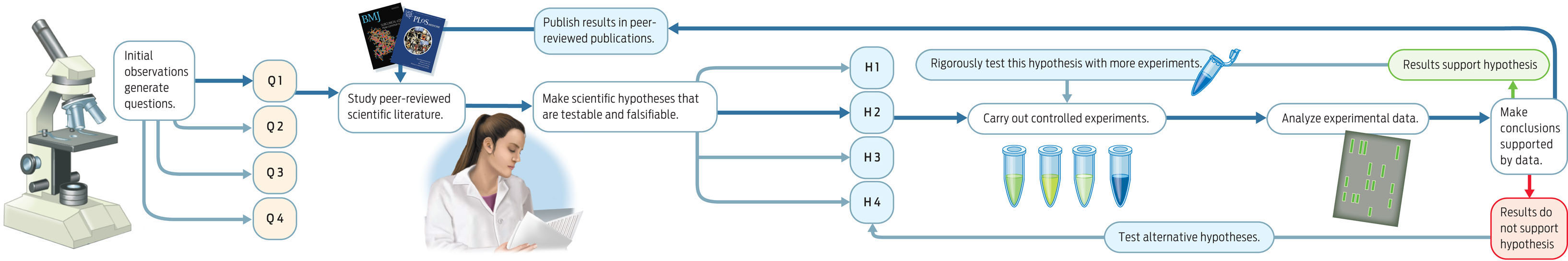

When many people think about science, they think of a body of facts to be memorized: water boils at 100°C; the nucleus is a part of a cell. But that’s not the whole story. Science is a way of knowing, a method of seeking answers to questions on the basis of observation and experiment. Scientists draw conclusions from the best evidence they have at any one time, and the process is not always easy or straightforward. Conclusions based on today’s evidence may be modified in the future as other scientists ask different—and sometimes better—questions. Moreover, with improved technology, researchers may uncover better data; new information can cast a new light on old conclusions. Science is a never-ending process.

ANECDOTAL EVIDENCE An informal observation that has not been systematically tested.

3

PEER REVIEW A process in which independent scientific experts read scientific studies before they are published to ensure that the authors have appropriately designed and interpreted the study.

Perhaps the best way to understand science is to do it. Let’s say you want to determine scientifically if coffee has energizing effects. How might you go about investigating this question? A logical place to start would be your own experience. You may notice that you feel more awake when you drink coffee or that coffee helps you concentrate. Such informal personal observations are called anecdotal evidence. This is a type of evidence that may be interesting but is often unreliable, since it isn’t based on systematic study. A poll of your classmates to find out how they experience coffee would also be anecdotal evidence.

Nevertheless, this anecdotal evidence might lead you to formulate a question: Does coffee improve mental performance? Will it help me study or do better on a test? To find out what information currently exists on the subject, you could read relevant studies that have already been conducted, available in online databases of journal articles or in university libraries. Generally, you can trust the information in scientific journals because it has been subject to peer review. The aim of peer review—the review of an article by experts before publication—is to weed out sloppy research as well as overstated claims, and thus ensure the integrity of the journal and its scientific findings. To further reduce the chance of bias, authors must declare any possible conflicts of interest and name all funding sources (for example, pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies). With this information, reviewers and readers can view the study with a more critical eye.

From your perusal of the scientific literature, you would soon discover (if you didn’t know it already) that coffee contains caffeine, and that caffeine is a chemical known to stimulate the brain. Brain regions controlling sleep, mood, memory, and concentration are especially sensitive to this chemical, and some researchers believe that caffeine accounts for the general feeling of alertness that many coffee drinkers experience.

HYPOTHESIS A tentative explanation for a scientific observation or question.

4

TESTABLE A hypothesis is testable if it can be supported or rejected by carefully designed experiments or observational studies.

Armed with this information, you could go one step further and formulate a specific hypothesis about how coffee affects mental performance. A hypothesis is a possible answer to the question under investigation. For example, one hypothesis about coffee might be that consuming the caffeine in coffee improves memory. Another might be that high levels of caffeine increase concentration. Not all possible explanations will be scientific hypotheses, though. A scientific hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable—that is, it can be established or rejected by experiment; and if it is false, it can be proved wrong. Statements of opinion and hypotheses that depend on supernatural or mystical explanations that cannot be tested or refuted fall outside the realm of scientific explanation. (Some call such explanations “pseudoscience”; astrology is a good example.)

FALSIFIABLE Describes a hypothesis that can be ruled out by data that show that the hypothesis does not explain the observation.

With a clear scientific hypothesis in hand—“caffeinated coffee improves memory”—the next step is to test it, generating evidence for or against the idea. If a hypothesis is shown to be false—if the finding is “caffeinated coffee does not improve memory”—the hypothesis can be rejected and removed from the list of possible answers to the original question. You, the scientist, are then forced to consider other hypotheses. On the other hand, if data support the hypothesis, then it will be accepted, at least until further testing and data show otherwise. Because it is impossible to test whether a hypothesis is true in every possible situation, a hypothesis can never be proved true once and for all. The best we can do is support the hypothesis with an exhaustive amount of evidence (INFOGRAPHIC 1.2) .

Multiple scientists doing multiple experiments narrow down the pool of possible hypotheses. Those that are rigorously tested and supported by other experiments emerge with greatest confidence.

EXPERIMENT A carefully designed test, the results of which will either support or rule out a hypothesis.

EXPERIMENTAL GROUP The group in an experiment that experiences the experimental intervention or manipulation.

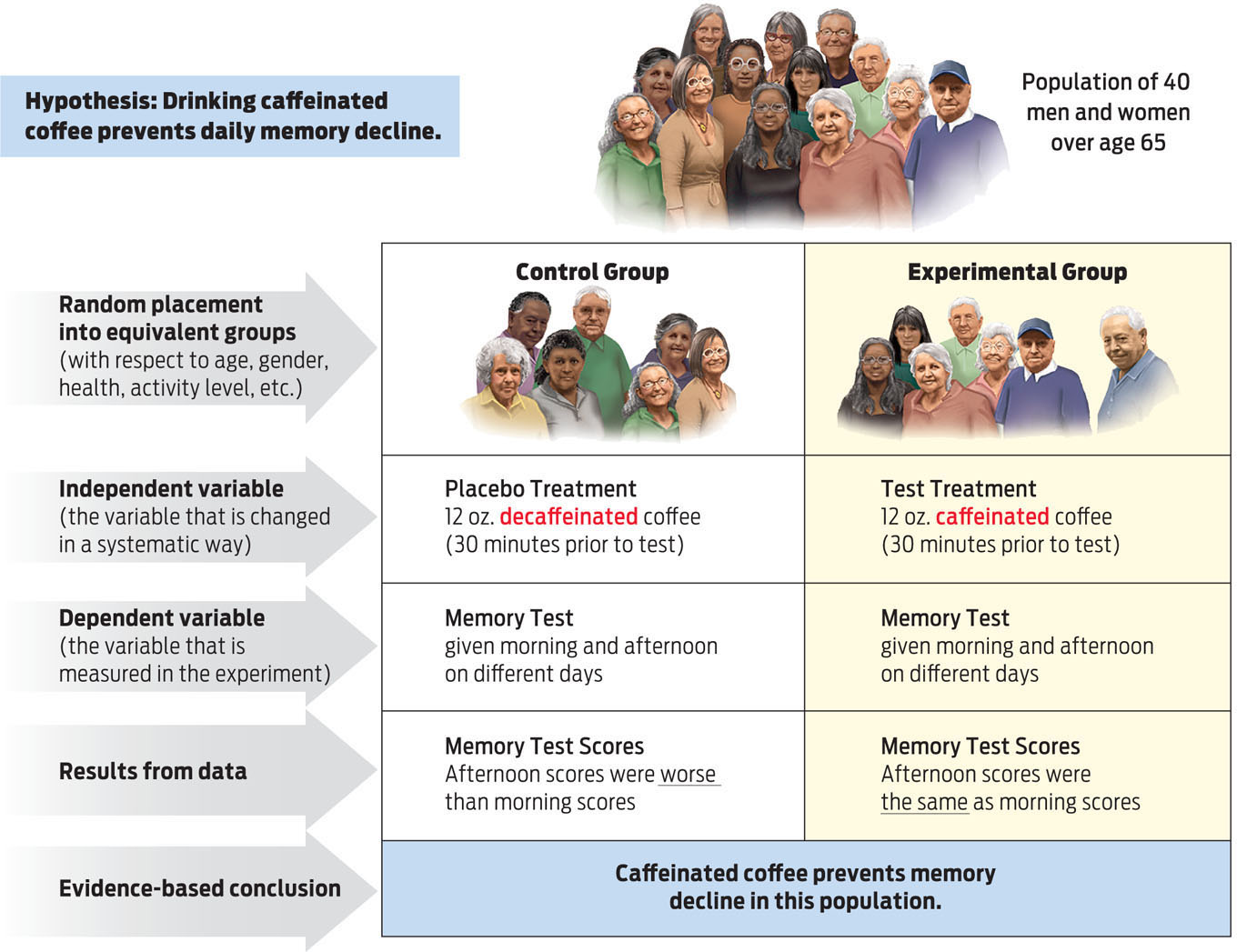

There are a number of ways in which a hypothesis can be tested. One is to design a controlled experiment. In this case, you might measure the effects of coffee drinking on a group of participants. In 2002, Lee Ryan, a psychologist at the University of Arizona, decided to do just that. Ryan noticed that memory is often optimal early in the morning in adults over age 65 but tends to decline as the day goes on. She also noticed that many adults report feeling more alert after drinking caffeinated coffee. She therefore hypothesized that drinking coffee might prevent this decline in memory, and devised an experiment to test her hypothesis.

CONTROL GROUP The group in an experiment that experiences no experimental intervention or manipulation.

First she collected a group of participants—40 men and women over age 65, who were active, healthy, and who reported consuming some form of caffeine daily. She then randomly divided these people into two groups: one that would get caffeinated coffee, and one that would receive decaf. The caffeine group is known as the experimental group, since these participants are receiving the factor being tested—in this case, caffeine. The decaf group is the control group, which serves as the basis of comparison. Both groups were given memory tests at 8 A.M. and again at 4 P.M. on two nonconsecutive days. The experimental group received a 12-ounce cup of regular coffee containing approximately 220–270 mg of caffeine 30 minutes before each test. The control group received a placebo: a 12-ounce cup of decaffeinated coffee containing no more than 5–10 mg of caffeine per serving. No participants knew to which group they were assigned—in other words, the study was “blind.” (In a “double-blind” study, neither the investigator nor the participants know who is getting what treatment.)

PLACEBO A fake treatment given to control groups to mimic the experience of the experimental groups.

5

6

INDEPENDENT VARIABLE The variable, or factor, being deliberately changed in the experimental group.

By administering a placebo, Ryan could ensure that any change observed in the experimental group was a result of consuming caffeine and not just any hot beverage. In addition, all participants were forbidden to eat or drink any caffeine-containing foods or drinks—like chocolate, soda, or coffee—for at least 4 hours before each test. Thus, the control group was identical to the experimental group in every way except for the consumption of caffeine.

DEPENDENT VARIABLE The measured result of an experiment, analyzed in both the experimental and control groups

In this experiment, caffeine consumption was the independent variable—the factor that is being changed in a deliberate way. The tests of memory are the dependent variable—the outcome that may “depend” on caffeine consumption.

Ryan found that participants who drank decaffeinated coffee did worse on tests of memory function in the afternoon compared to the morning. By contrast, the experimental group who drank caffeinated coffee performed equally well on morning and afternoon memory tests. The results, which were reported in the journal Psychological Science, support the hypothesis that caffeine, delivered in the form of coffee, prevents the decline of memory—at least in certain people (INFOGRAPHIC 1.3) .

There are many ways to approach a scientific problem. Controlled experiments are one way. As illustrated here, controlled experiments have two groups—the control group and the experimental group—that differ only in the independent variable.

7

Because other factors might possibly explain the link between coffee and mental performance (perhaps coffee drinkers are more active, and their physical activity rather than their coffee consumption explains their mental performance), it’s too soon to see these results as proof of coffee’s memory-boosting powers. To win our confidence, the experiment must be repeated by other scientists and, if possible, the methodology refined.