448

DRIVING QUESTIONS

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- What is ecology, and what do ecologists study?

- What are the different patterns of population growth?

- What factors influence population growth and population size?

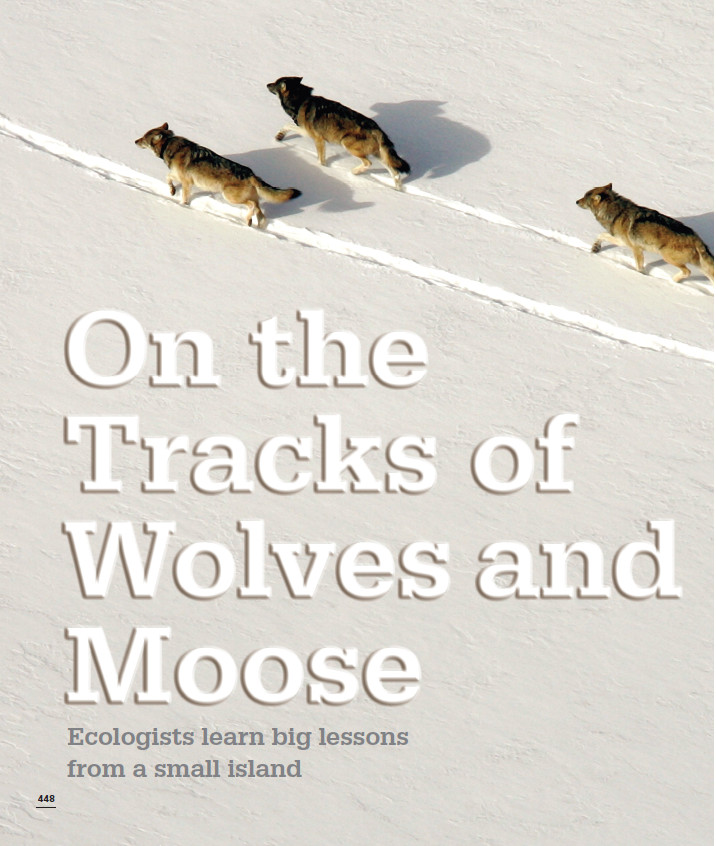

OHN VUCETICH SPENT A FREEZING FEBRUARY DAY IN 2010 trudging through knee-high snow on an island in Lake Superior. He was tracking a young gray wolf he called Romeo. The tracks led to a site in the forest where cracked branches and crimson-stained snow were evidence that a violent struggle had taken place just hours earlier. Later, thawing in his cabin beside a wood-burning stove, Vucetich wrote in his field journal:

OHN VUCETICH SPENT A FREEZING FEBRUARY DAY IN 2010 trudging through knee-high snow on an island in Lake Superior. He was tracking a young gray wolf he called Romeo. The tracks led to a site in the forest where cracked branches and crimson-stained snow were evidence that a violent struggle had taken place just hours earlier. Later, thawing in his cabin beside a wood-burning stove, Vucetich wrote in his field journal:

Teeth, hooves, blood, bruises, adrenaline, exhaustion. Romeo killed a moose. Very likely, this is the first moose he’d ever killed. He’d seen his parents, the alpha pair of Chippewa Harbor Pack, do it many times…. He’d wounded moose a couple of times this winter, but never killed one.

450

Isle Royale is not too big and it’s not too small and it’s not too close and not too far. It’s just the right size to have a population of wolves and moose that we can study.

Isle Royale is not too big and it’s not too small and it’s not too close and not too far. It’s just the right size to have a population of wolves and moose that we can study.

— JOHN VUCETICH

For nearly 20 years, Vucetich has been shadowing wolves like Romeo and his kin on Isle Royale, a remote island about 15 miles off the Canadian shore in the northwest corner of Lake Superior. A 200-square-mile slice of roadless wilderness that is accessible only by boat and seaplane, Isle Royale may seem an unlikely place for a scientific laboratory, but that’s exactly what it is for Vucetich and his colleagues. Every summer, and for a few weeks every winter, they investigate the island’s packs of gray wolves (Canis lupis) and the herd of moose (Alces alces) that are their prey.

ECOLOGY The study of the interactions between organisms and between organisms and their nonliving environment.

Begun in 1958, the Isle Royale wolf and moose study is the longest-running predator-prey study in the world. For more than 50 years, researchers have studied how these two island inhabitants have interacted and coexisted in this wild place. They are motivated by a simple yet increasingly pressing goal: “to observe and understand the dynamic fluctuations of Isle Royale’s wolves and moose, in the hope that such knowledge will inspire a new, flourishing relationship with nature,” according to study’s annual report.

Islands have long provided biologists with important lessons about nature—think of Darwin and Wallace and their island adventures. But none has ever produced such a mountain of data for researchers interested in ecology, the study of the interactions between organisms and between organisms and their nonliving environment. At a moment when wild populations are threatened all over the world, the lessons of Isle Royale couldn’t have come at a better time.