ECOLOGIAL DETECTIVES

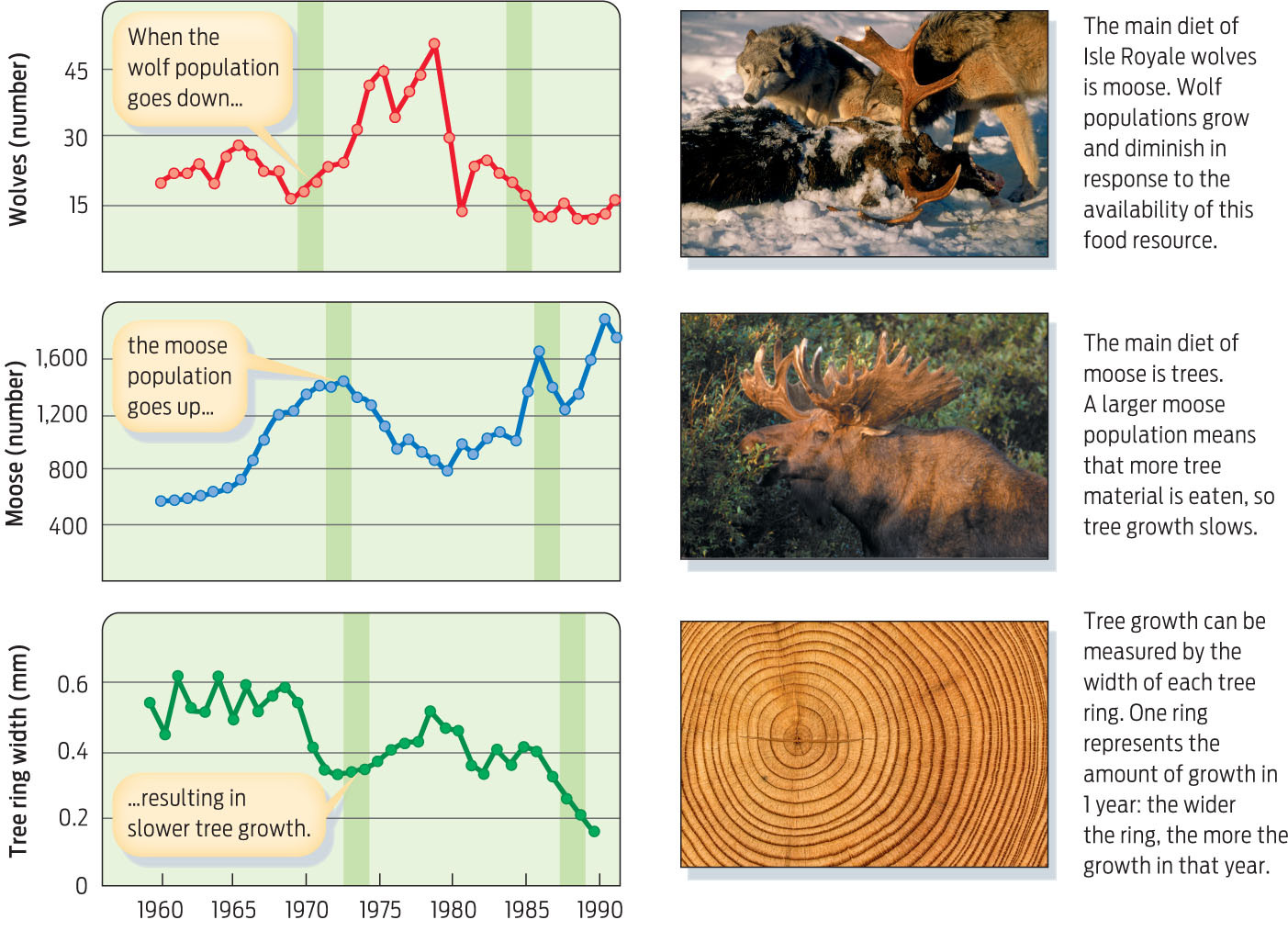

The size of the wolf population affects more than just the size of the moose population. Another pattern that has emerged in the decades of data collected on Isle Royale is a correlation between a large wolf population and vigorous tree growth. When wolves are plentiful, they keep the moose population in check. Because trees are the primary food source for moose, they grow more when fewer moose are eating them. It’s therefore possible to follow the rise and fall of the wolf population by monitoring the state of the forest.

One way ecologists can determine forest growth and health is to count and measure the width of tree rings, which reflect how much trees have grown season by season. They also measure the height of the trees. Taller and bigger trees mean that fewer moose have been foraging on them, which in turn indicates that more wolves have been keeping the moose population in check.

Wolves affect tree growth in another, and indirect, way as well. Because the wolves don’t always consume the entire carcass of a moose they kill, the remains decay and fertilize the ground where they lie, enriching the soil with nutrients for plant growth. Researchers have found that nitrogen levels are between 25% and 50% higher in these hot spots compared to control sites. This work shows that predators—in this case, wolves—are an important component of a balanced and healthy ecosystem and illustrates what can be lost when predators are eliminated (INFOGRAPHIC 21.6) .

Wolf, moose, and tree populations are all interconnected. Trees provide food for moose, and moose provide food for wolves. Anything that impacts the size of one population will impact the size of the others.

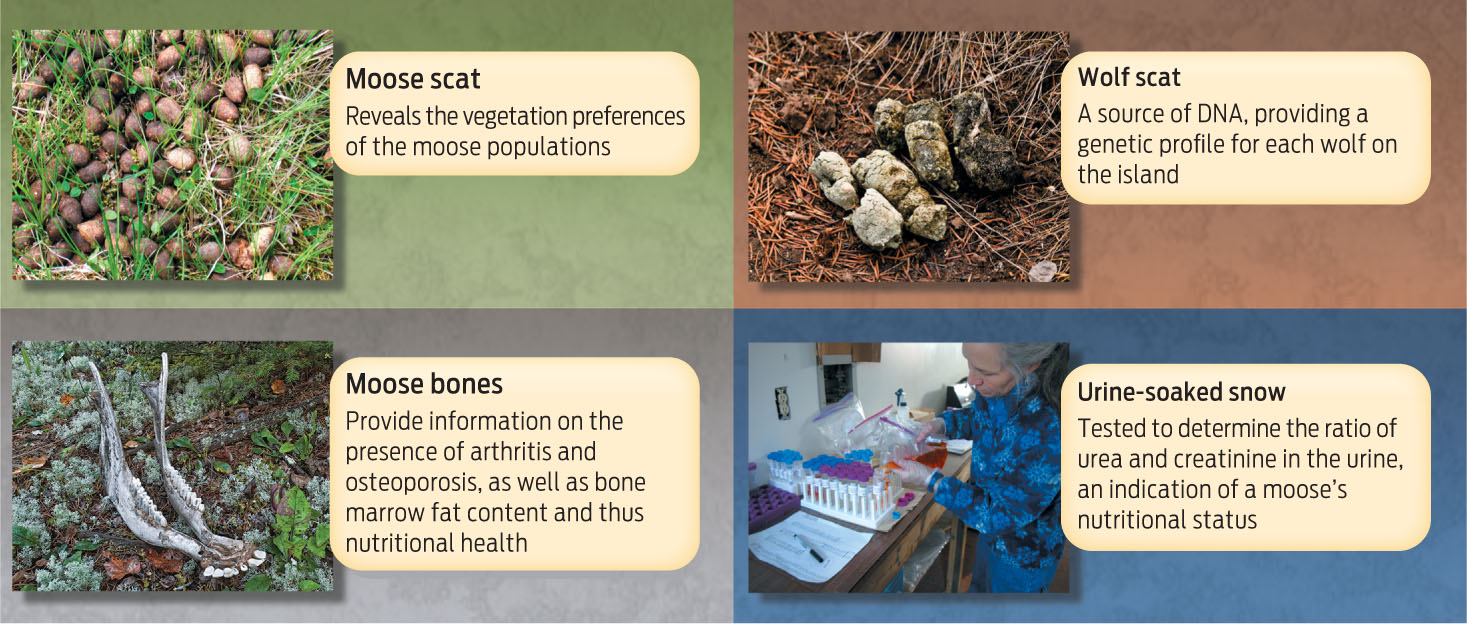

Another clue the ecological detectives look at is urine-soaked snow and droppings, or scat. Urine and scat may seem crude objects of scientific study, but they reveal a host of information about the animal that produced them. By analyzing moose scat samples under the microscope, researchers can tell exactly what moose have been eating. During the winter months, for example, moose eat mostly twigs from deciduous (leaf-shedding) plants and needles from balsam fir and cedar trees. Knowing a moose’s diet is important because the supply of balsam fir on the island has been steadily dwindling over the years. By monitoring moose scat, researchers will be able to tell if moose are able to switch over to other, more common food items.

457

Scat also provides important information about an animal’s genetics. It is used to obtain DNA profiles, for example, which can be used to confirm population counts and to track which wolves were involved in killing which moose. DNA can also be used to look for diseases or signs of inbreeding. “Through the DNA we can get a good sense of individual wolves—how they live and how they die,” says Vucetich. (For more information on DNA profiling, see Chapter 7.)

Yet more clues can come from studying a moose kill site, which is a bit like analyzing a crime scene. Researchers can tell if a moose was killed by wolves because in that case there will often be blood spattered on nearby trees and signs of struggle in the form of broken branches. Wolves also typically scatter bones as they feast, whereas the carcasses of moose that die of starvation may be relatively intact.

At the kill site, researchers gather moose bones. From these bones, the researchers can tell how old a moose was when it died, as well as learn about other aspects of the animal’s health, such as whether it had arthritis or osteoporosis. The value of this information goes beyond understanding individual animals. It allows researchers to know whether wolves are targeting healthy moose or sickly ones. Killing a healthy moose has a bigger effect on moose population dynamics than killing one that is already near death, because a young, healthy moose might have gone on to reproduce had it lived (INFOGRAPHIC 21.7) .

In addition to information about population size, researchers collect other data that are essential for monitoring the physical health of moose and wolf populations.

458