WATCHING AND WAITING

For the scientists on Isle Royale, population ecology is full of unexpected twists and turns. There is often no sure way to know how various environmental factors will influence the growth of a population. Even on an isolated island with only one large predator and one large prey, population dynamics are never simple. Scientists gather data, look for patterns, and form hypotheses, but predicting what will happen next is much more difficult. “What Isle Royale has shown us—and has shown us convincingly for the past 50 years—is that we’re lousy at predicting the future,” says Vucetich. “What we’re a fair bit better at is explaining the past.”

For example, beginning around 1980, a disease called canine parvovirus (CPV) infected Isle Royale’s wolves. The disease typically affects domestic dogs and was likely brought unintentionally to the island on the boots of hikers. The disease killed all but 14 of the island’s wolves, and over the next 10 years the moose population skyrocketed, suggesting that wolves exert a strong influence on the abundance of their prey. The event was useful from a scientific standpoint—but entirely unexpected. “There’s no way that anyone could have predicted that. Not in a million years,” says Vucetich.

That wasn’t the end of the surprises. In the last 15 years, it’s become apparent that a warming climate, not just predation by wolves, is influencing moose population size. The first decade of the 21st century was one of the hottest on record. Sweltering summer temperatures hit moose especially hard. The large herbivores get hot easily, and they don’t perspire; they escape the heat by resting in the shade. A lot of time spent resting means less time for eating, and a moose who eats less all summer has less insulation for winter.

461

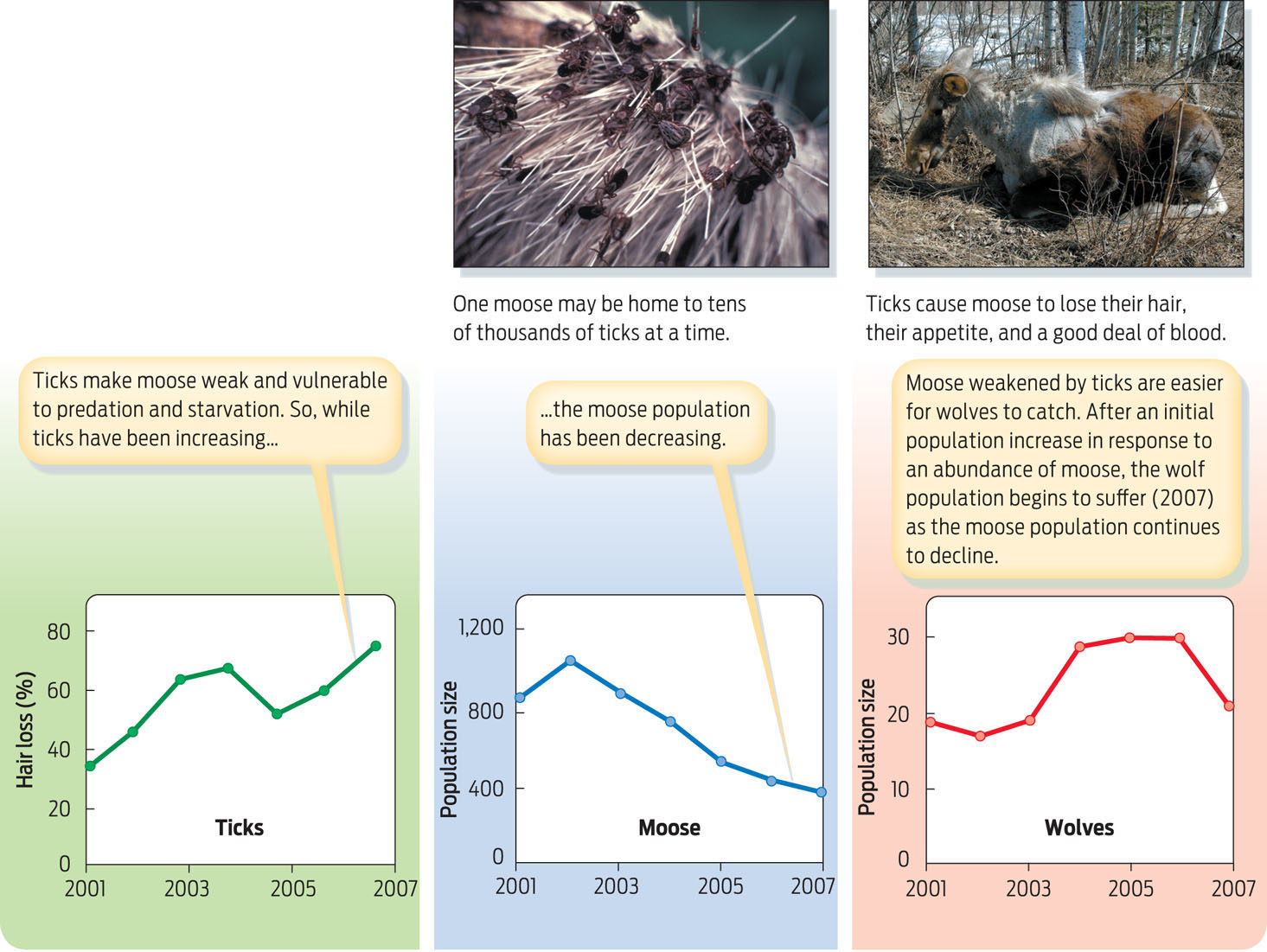

Warmer temperatures have affected moose in a more insidious way as well. About 10 years ago, Vucetich and his colleagues began to notice that a tick parasite was bothering the moose, and that warm weather seems to favor ticks. Ticks suck the moose’s blood and cause them to itch. The moose scratch themselves against trees and chew their hair out trying to rid themselves of the itchy freeloaders. Since a single moose may host many thousands of ticks, the combination of tick-related blood loss and heat-induced weight loss can be deadly. In 2004, the average moose had lost more than 70% of its body hair, the result of carrying more than 70,000 ticks.

By 2007, the deadly combination of bloodsucking ticks, hot summers, and relentless predation from wolves had driven the moose population to its lowest point in at least 50 years—385, down from 1,100 in 2002. Predictably, the wolf population followed suit, declining from 30 individuals in 2005 to 21 in 2007. As of 2013, the moose population was back up to about 975 moose, while the wolves declined to just 8 individuals (INFOGRAPHIC 21.9) .

In recent years, climate change has become a significant influence on moose and wolf populations on isle Royale. Warmer temperatures lead to increased tick infestations of moose, resulting in a weakened and depleted population.

Hunted by wolves, preyed on by ticks, dogged by oppressive heat, moose certainly do not have it easy. They can live to be 17 years old, but most moose die before reaching their tenth birthday.

Life is no picnic for wolves, either. While they can live to be 12 years old, most die by age 4. The most common cause of death is starvation. With few available food sources, a wolf may go 10 days without eating. Obtaining a meal on the eleventh day may mean having to wrestle a 900-pound moose on an empty stomach.

The difficulty of finding food is just one obstacle for wolves. They also have a high incidence of bone deformities, which cause back pain and partial paralysis of the hind legs. In the early years of the Isle Royale study, such deformities were rare, but they’ve become more common in recent years, almost certainly a result of inbreeding. For the last 15 years, every dead wolf on Isle Royale has had such deformities. Vucetich thinks that climate change may be an indirect cause of the inbreeding by lessening the frequency that ice bridges form between Canada and Isle Royale, bridges over which new wolves could reach the island and diversify the wolf gene pool.

It’s not the first time wolf populations have been in trouble. When colonial settlers first arrived in North America, the gray wolf roamed throughout all of the future 48 contiguous U.S. states. By 1914, hunting and trapping had greatly reduced the population, and survivors were limited to remote wooded regions of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The federal government officially listed the species as endangered in the early 1970s, when it seemed on the verge of extinction. Since then, as a result of conservation efforts, wolves in other areas have started to bounce back: there are an estimated 7,000 to 11,000 gray wolves in Alaska, and approximately 5,000 in the rest of the country. But on Isle Royale, wolves are at their lowest numbers since the study began.

The Isle Royale wolves’ latest plight poses an ethical dilemma: should scientists intervene on their behalf—say, by importing wolves from another population to reintroduce genetic diversity—or let nature take its course? It’s a question that Vucetich thinks about a lot. The answer, he says, will require balancing a number of competing values—not just the value of individual populations, but the values of ecosystem health, scientific knowledge, and wilderness. Without wolves, for example, would the moose population once again explode and decimate the island’s forest? Would healthier wolves be able to completely overwhelm moose, and drive them to extinction on the island? Does the fact that human-caused climate change has worsened these problems mean that we have a moral obligation to alleviate them? These are some of the difficult questions that wildlife managers will need to consider when debating whether and how to intervene.

462

The dilemma is a familiar one to conservation biologists. According to Vucetich, these competing values show up in varying degrees in almost any management question that we have in any part of the world. They represent, he says, “this grand question of How should humans relate to nature?” There are no easy or obvious answers. Nevertheless, he believes it is important for people to debate and discuss these issues—not just scientists and experts, but lay people, too, because “every citizen has a stake in this question of how we relate to nature.”

463