COMPETING FOR RESOURCES

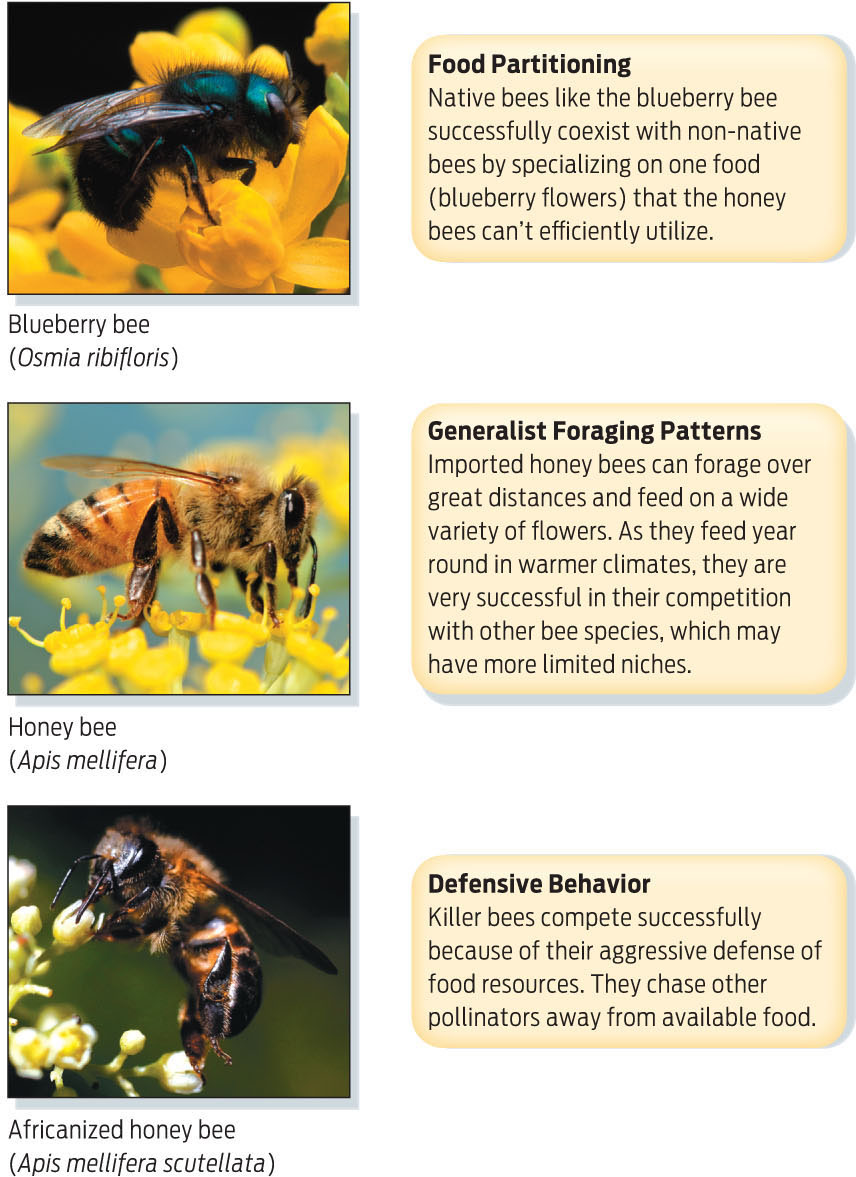

When European settlers first brought the Western honey bee to the United States in the 1600s, the bees quickly spread from managed colonies into the wild, in some cases displacing native bee species. Honey bees are excellent at colonizing new habitats because they are largely generalists when it comes to flower choice.

NICHE The space, environmental conditions, and resources that a species needs in order to survive and reproduce.

477

Though they tend to visit a single species of flower on each foraging trip, honey bees may visit more than 100 species of flowers within a single geographic region over the course of a season. In warm climates, they are active year round, and tend to feed throughout the day and start foraging earlier in the morning than many native bee species. In other words, honey bees have a broad ecological niche–the space, environmental conditions, and resources (including other living species) that a species needs in order to survive and reproduce.

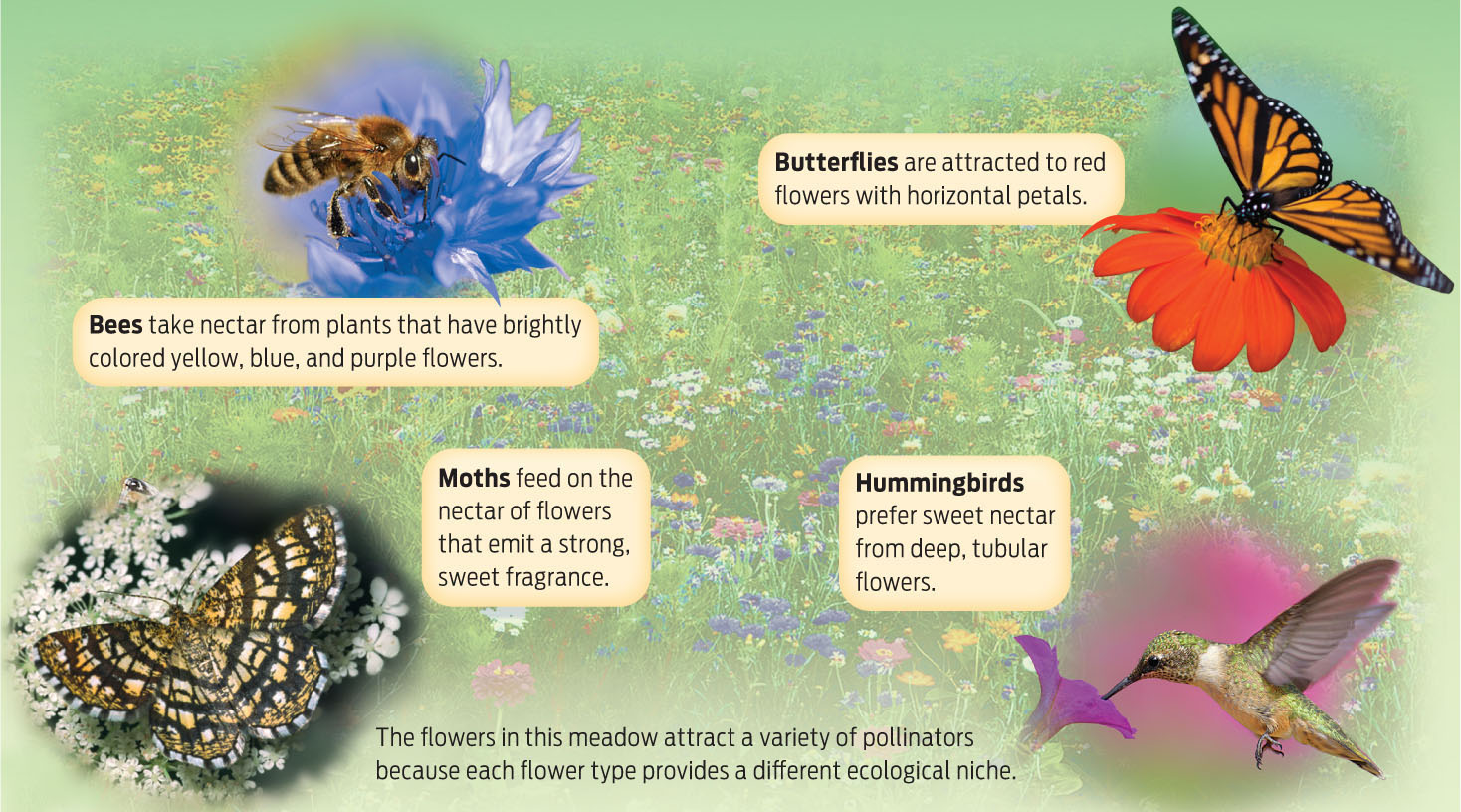

Different pollinators generally have different niches, owing to their varying sizes and preferences for different flower types. Bees, for instance, are attracted to brightly colored blossoms–those with yellow, blue, and purple petals, for example, but not red. Butterflies, by contrast, are commonly attracted to red flowers that are large and easy to land on. Moth-pollinated flowers tend to have pale or white petals with no distinctive color pattern but with strong fragrance (INFOGRAPHIC 22.7) .

Some pollinators share similar but not identical ecological niches. They may require the same seasonal temperatures, structures for shelter, yearly rainfall, and food from the nectar and pollen of flowers but prefer flowers of different size, color, and shape.

COMPETITION An interaction between two or more organisms that rely on a common resource that is not available in sufficient quantities.

COMPETITIVE EXCLUSION PRINCIPLE The concept that when two species compete for resources in an identical niche, one is inevitably driven to extinction.

When two or more species rely on the same limited resources–that is, when their niches overlap–the result is competition. Competition tends to limit the size of competing populations and may even drive one out. In theory, no two species can successfully coexist in identical niches in a community because one would eventually out-compete the other–a concept described by the competitive exclusion principle. In reality, however, very few species share exactly the same niche, so different species may find a competitive balance by subdividing resources (so-called “resource partitioning”).

Some species compete through behavior. African honey bees (Apis mellifera scutellata), for example, are a subspecies that was brought from Africa to Brazil in 1956 and which quickly expanded its range to include Central America and the southern United States. When African bees mate with local varieties they produce hybrid species with a blend of traits: these so-called Africanized honey bees are much more aggressive than Western honey bees. They will chase away other pollinators from food sources, and even swarm and sting animals that get near their hives–behaviors earning them the colloquial name “killer bee” (INFOGRAPHIC 22.8) .

Species with similar niches compete for resources that may be limited because of natural or human influences. Species may out-compete one another or find a balance, depending on their foraging abilities and behaviors.

478

Some scientists are worried that killer bees from Central America may displace or interbreed with U.S. populations of Western honey bees, with potentially disastrous results for beekeeping and agriculture. This hasn’t happened–yet. The much more serious problem for the Western honey bee, it seems, is competition from an even more dangerous species: humans. Humans and their activities have limited the resources used by bees and other pollinators. Agriculture, suburban sprawl, and development, for example, have all decreased bees’ natural forage areas, and fragmented their habitat into nonoverlapping zones. Unable to access as many resources in a single foraging trip, bees must compete with each other in the patches that remain.

The ubiquitous well-manicured lawn is particularly problematic. An immense stretch of green grass and no flowers, a lawn is “basically a desert to pollinators,” says Frazier. There is literally nothing for them to eat. Likewise, many agricultural areas are planted with monocultures (that is, single crops), which all bloom at the same time, leaving no flowers for the rest of the year. Worse yet, certain genetically engineered pollen-free crops trick bees into thinking they’ll find food, only to leave them hungry. And certain non-native plants have floral structures that are inaccessible to indigenous pollinating insects.

As a consequence of these and other human actions, in some geographic regions bees must compete both with one another and with other pollinators for a dwindling supply of food-providing flowers. Many are going hungry and thus are left vulnerable to conditions that can lead to CCD.