HONEY BEE IN THE COAL MINE?

Honey bees aren’t the only pollinator in peril. According to a report published in 2007 by the National Research Council, the number and abundance of pollinator species have declined greatly over the last several years. In fact, several bumblebee species are becoming or have become extinct in North America. The concern among researchers and beekeepers is that honey bees may be the “canary in the coal mine,” forecasting what’s in store for other pollinators. “It’s not only the honey bees that are in trouble,” says Hackenberg. “All the beneficial insects are in a bad situation.”

479

What’s ailing these insects? In addition to a shrinking and fragmented habitat, a disquieting possibility is that they are being poisoned by pesticides. Penn State researcher Frazier and her colleagues have looked at pollen and wax from beehives and found large amounts of many different kinds of pesticides, some of which are approaching toxic levels for the bees. “Pesticides are definitely in the mix and we think they are definitely a player in the stresses that bees are experiencing,” says Frazier.

Of particular concern to beekeepers is a class of pesticides known as neonicotinoids, or “neonics” for short. Neonics are an artificial form of nicotine heavily used in commercial agriculture all over the world. (Nicotine, made by tobacco plants, is a natural deterrent to plant-eating insects.) Virtually all corn and most soybean seeds in the U.S. are treated with neonics. Research has shown that neonics can impair honey bees’ ability to find and return to their hives, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) acknowledges that neonics are “highly toxic to honey bees.” Yet so far the EPA has not restricted use of these pesticides in the U.S. A 2012 report produced by the USDA acknowledged that neonics and other pesticides may be a contributing factor to CCD, but stopped short of singling them out as a primary cause. “The bottom line is we have not been able to put together, here in the United States, the evidence that neonicotinoids are causing the decline in honeybees,” says Frazier. “But we are not convinced that they are not playing a role.”

All the evidence so far has really supported the idea that it’s likely a combination of factors that are stressing the bees beyond their ability to cope. 99

All the evidence so far has really supported the idea that it’s likely a combination of factors that are stressing the bees beyond their ability to cope. 99

–MARYANN FRAZIER

480

The situation is a bit different in Europe. In 2013, the European Union imposed a two-year continent-wide ban on neonicotinoids on flowering crops such as corn, rapeseed, and sunflowers that are attractive to bees, after a report by the European Food Safety Authority identified a number of risks posed to bees from the pesticides. The short-term ban will allow researchers the chance to study the effects of neonics more thoroughly–especially at the sublethal doses bees are likely to encounter.

Although researchers have not yet been able to prove that neonics are playing a role in CCD–“the jury is still out,” says Frazier–bee-keepers like Hackenberg are understandably cautious about what pesticides they expose their colonies to (INFOGRAPHIC 22.9) .

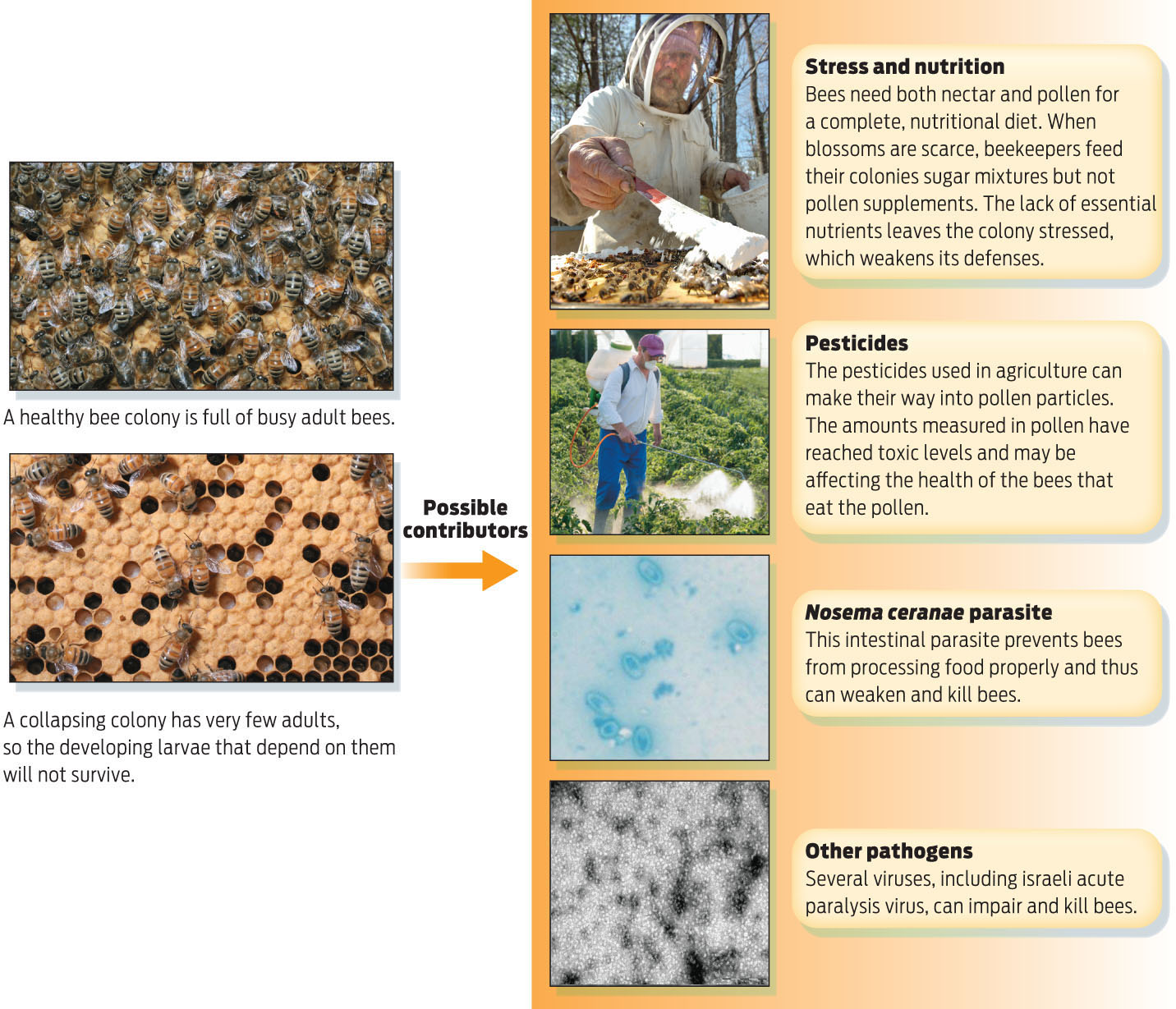

Bees live in a social colony with a single queen and her offspring. The collapse of colonies all over the world is of great concern. The cause of this disorder is likely to be complex and to involve an interplay of several factors.

Because it may involve a complex combination of triggers, there is no easy remedy to CCD. It may require making fundamental changes to our beekeeping and agricultural practices. In particular, we could break up fields of monocultures with varied bee-friendly plants: red clover, foxglove, and bee balm, for example. We could also use pesticides sparingly and avoid spraying at times of day when bees are actively foraging (although this won’t help with neonics, which are applied to the seeds themselves before they get planted).

481

While these individual steps would certainly help matters, apiarist Dennis vanEngelsdorp diagnoses a more systemic problem. In his estimation, we suffer from NDD–“nature deficit disorder.” To help bees, he says, we need also to cure ourselves. As treatment, he prescribes reconnecting to nature in a more immediate and local way–“having a meadow or living by a meadow,” for example, or becoming a beekeeper oneself.

In addition, says bee expert Frazier, “People need to take more time to understand where their food comes from, what it takes to produce food and have this incredible supply of food available to us.”

While the fate of the honey bees remains uncertain, there are signs that a more bee-friendly awareness is beginning to emerge, thanks in part to the concerns raised by CCD. In 2008, Häagen-Dazs, the ice-cream maker, launched a “Help the Honey Bee” campaign, in recognition of the fact that honey bee–dependent products are used in 25 of its 60 flavors. So far, the company has donated more than $700,000 to honey bee research at universities including the University of California-Davis and Penn State University. Burt’s Bees, the maker of “Earth-friendly” lip balms and other personal products, has created a series of CCD-related public service announcements, viewable on YouTube, including one starring Isabella Rossellini dressed as a honeybee. Even ordinary citizens are catching the bee buzz. From city-dwellers becoming amateur rooftop beekeepers to suburbanites letting more flowers grow in their yards, the ranks of people wanting to make the environment pollinator-friendly has swelled. And that’s a cause that just about everyone can get behind–because, as more and more people are coming to realize, a world without honey bees just wouldn’t be as sweet.

482