NOR ANY DROP TO DRINK

As any Kansas farmer will tell you, fossil fuels aren’t the only natural resources being overdrawn by a growing human population—water is, too. “We are so dry right now,” says urban planner White.

536

537

For residents of Kansas and other states of the Great Plains, water for drinking and irrigation comes from the large Ogallala Aquifer, a deep underground source of water spanning eight states in the middle of the country. Rain is so scarce in this part of the United States that, were it not for the aquifer, it would be a desert. Thanks to the aquifer, it is one of the most fertile agricultural regions in the world.

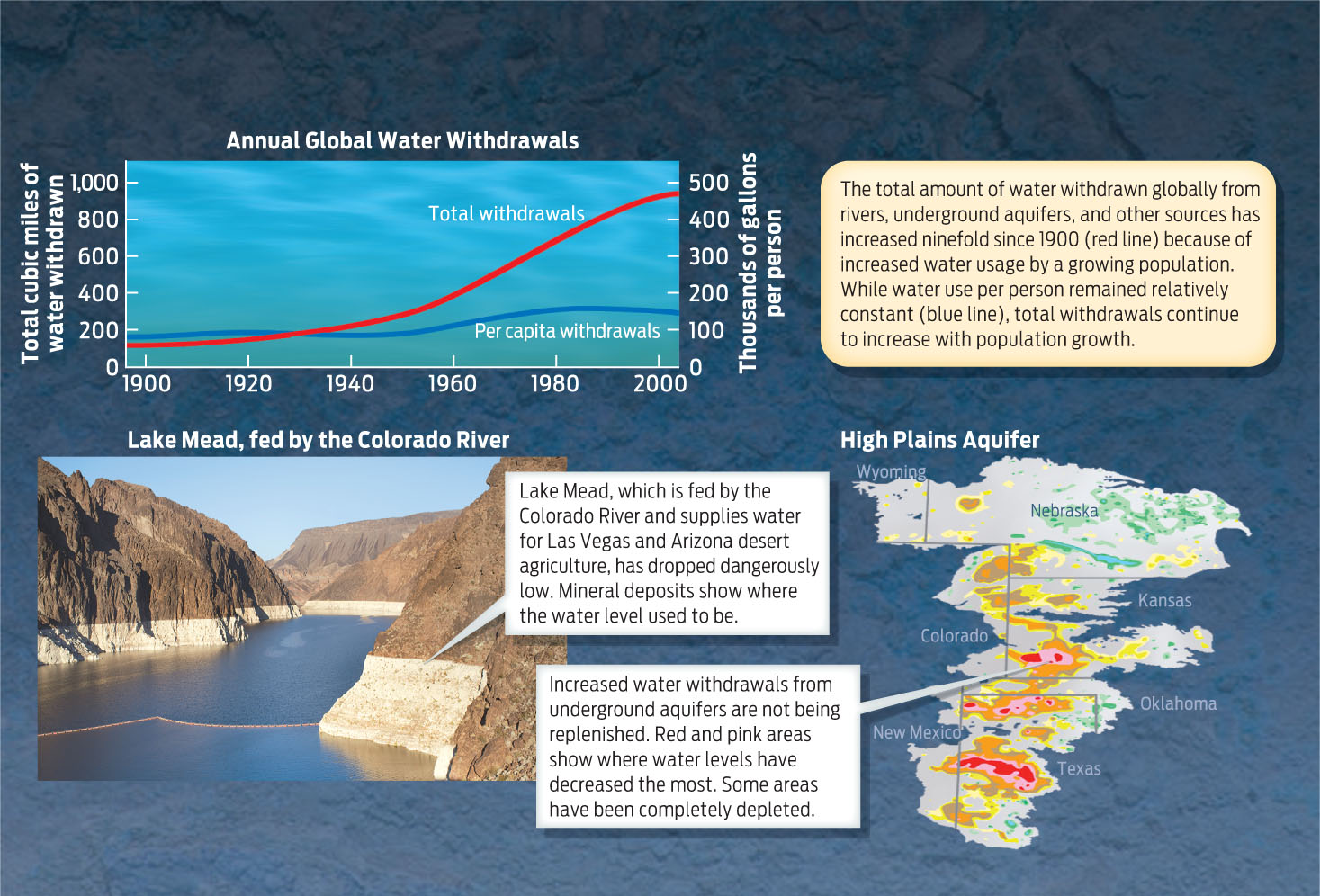

Studies by the U. S. Geological Survey and others suggest that the Ogallala, also known as the High Plains Aquifer, is being depleted faster than it is being replenished, and some experts predict that it could dry up by 2050. The aquifer is at “historical lows right now,” White says.

To help conserve water, many buildings in Greensburg have rooftop rain filtration and storage systems, which collect rainwater and use it to flush toilets and irrigate the grounds. Rain barrels to collect water are also becoming quite common in many parts of Kansas.

The very fact of water shortages may seem counterintuitive. After all, 70% of the globe’s surface is covered with water. But of this vast supply, only 2.5% is freshwater, and most of that is locked up in ice caps and glaciers. A meager 1% of the total water on Earth is available for human consumption.

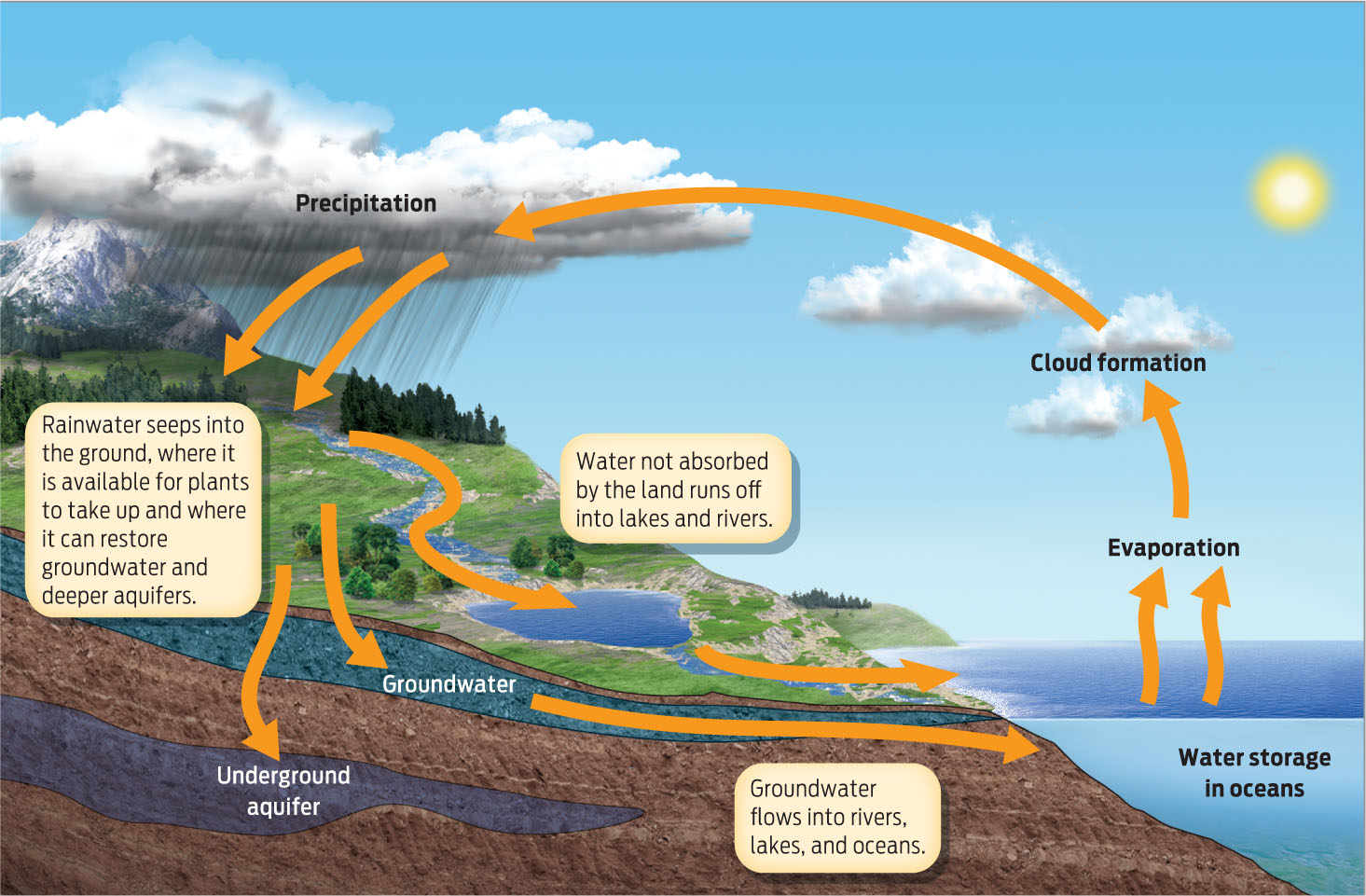

Nevertheless, freshwater is considered a renewable resource because the supply in lakes, rivers, reservoirs, and underground aquifers is continually being replenished by the water cycle. As long as the rate of water withdrawal from these sources is less than the rate of replacement, the supply of freshwater remains relatively constant (INFOGRAPHIC 24.8) .

Freshwater is a valuable resource. In addition to its role in keeping us hydrated, it irrigates crops, sustains fisheries, and provides recreational opportunities. Although water is “used,” it is not “used up”: it is ultimately returned to the global ecosystem as it evaporates to the atmosphere, flows into rivers or streams, or enters underground aquifers.

AQUIFER An underground layer of porous rock from which water can be drawn for use.

538

GREENSBURG STYLE: WATER CONSERVATION

Plants

Native plants are drought tolerant and require less watering

Native plants are drought tolerant and require less watering Landscaping minimizes rainwater runoff into city sewers—it filters and channels it for capture

Landscaping minimizes rainwater runoff into city sewers—it filters and channels it for capture Athletic fields are artificial turf that requires no watering

Athletic fields are artificial turf that requires no watering

Water Collection

Roofs tilted to channel rainwater

Roofs tilted to channel rainwater Gutter downspouts collect water in troughs

Gutter downspouts collect water in troughs 10k gallon aboveground cistern stores collected rainwater

10k gallon aboveground cistern stores collected rainwater 50k gallon belowground cistern stores water runoff

50k gallon belowground cistern stores water runoff

Irrigation

collected water used for irrigation of landscaping

collected water used for irrigation of landscaping Collected water used to flush water-conserving toilets

Collected water used to flush water-conserving toilets Waterless urinals save 0.5 gallons per use

Waterless urinals save 0.5 gallons per use

539

Although water is not consumed in the same way as coal or oil, our supply of freshwater is being divided among more and more people, so there is less available, on average, for each of us. According to the United Nations, water use increased sixfold during the 20th century, more than twice the rate of population increase. Today, more than half of all the accessible freshwater contained in rivers, lakes, and aquifers is appropriated by humans, most of it for irrigation in agriculture. A striking example of the consequences of increased water use can be seen in Lake Mead, which is fed by the Colorado River. This reservoir, which provides freshwater to much of the southwestern United States, is at historic lows today (INFOGRAPHIC 24.9) .

Water is pumped from rivers and lakes to irrigate dry land for agriculture. More than 90% of the world’s water usage is for agriculture. The demand for water can exceed the capacity of rivers, lakes, and aquifers to be replenished. During drought years, irrigation sources dry up, affecting aquatic species and human livelihood.

Pollution also shrinks the total amount of available clean freshwater on the planet. Agriculture, industry, and cities all play a role. Runoff from streets carries pollutants such as motor oil and sewage; fertilizers, pesticides, and toxic chemicals leach from fields and factories. These substances can eventually reach aquifers, rivers, and oceans, contaminating the water that both humans and wildlife depend on.

Food and lifestyle choices also affect water availability. According to environmental scientist Arjen Y. Hoekstra, it takes 900 liters of water to produce 1 kilogram of corn, but more than 15 times that to produce 1 kilogram of beef.

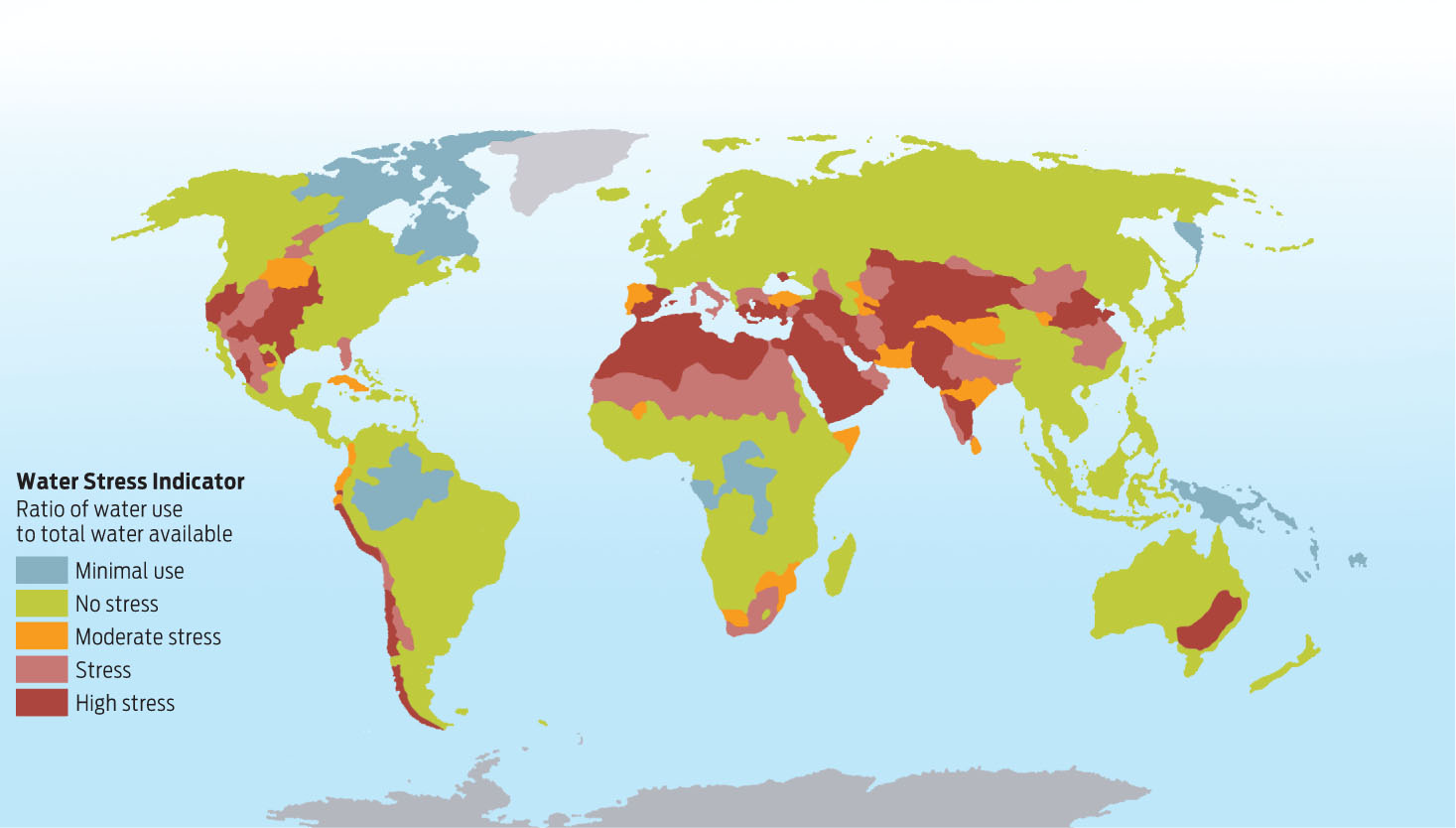

Some countries experience water scarcity more acutely than others. That’s because the geographic distribution of freshwater does not match the distribution of the world’s population. Canada has just 0.5% of the world’s population, but 20% of the global freshwater supply. The United Nations estimates that at least a billion people in the world currently lack access to clean and safe drinking water, and by 2025, two-thirds of the world’s population will live in areas of moderate to severe water stress. Climate change, if it changes precipitation patterns, may also affect the global availability of water in unpredictable ways (INFOGRAPHIC 24.10) .

Freshwater is not evenly distributed across the globe, and its availability does not always follow international borders. In addition, access to even a sufficient water supply may be limited by economic, social, and political circumstances, such as war and ethnic conflict. As the human population continues to grow, and access to clean freshwater continues to decline, these problems are likely to intensify, particularly in areas with existing scarcities of water.

540

In their sustainable building plan, Greensburg pledged to “treat each drop of water as a precious resource.”